Many flutists were introduced to the concept of note-grouping from John Krell’s Kincaidiana book. In this book, Krell shares, “He [Kincaid] devised a system of phrase groupings, consisting of a bracketing of related notes in a kind of family relationship, to show their identification with, and progression to, this finishing (final) note.” For example, scales beamed by four sixteenths, were grouped 1, 2341, 2341, 2341, etc. Note-grouping in no way affects the printed articulation or rhythm. However, when done properly, there is a slight, almost imperceptible sense of moving ahead or lagging behind rhythmically.

Through the years as more musicians worked with this idea, other grouping patterns emerged. To enhance the note-group, practice each note-group followed by a rest. We call this type of practicing chunking.

Vocalises

In developing a wind pedagogy, artist teachers/composers often borrowed ideas from the vocal and keyboard worlds. One common example is the vocalise which began as a singing exercise, executed on a vowel sound, to develop the tone, both in beauty and in homogeneity. (It is interesting to note that once one instrument had a set of vocalizes, they were often shared with other instrumentalists. For example, M. A. Reichert wrote the Seven Daily Exercises for Flute, Op. 5 (1872). These may also be found in the oboist’s famous Vade Mecum book.)

Some vocalises were written to be executed at a fast tempo to develop flexibility, while others primarily were intended to help a vocalist improve intonation and increase range. Vocalises were sung on each note of a chromatic scale sometimes ascending and other times descending. Their simplicity makes them perfect candidates to explore various note-grouping and phrasing ideas.

| Reichert For those who are reading about M.A. Reichert (1830-1880) for the first time, he was a virtuoso flutist who trained at the Brussels Conservatory. In 1859, he along with several other virtuoso performers arrived in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil where he toured as a soloist and became first flute in the Teatro Provisorio. He is remembered for introducing the new Boehm flute to local flutists. During his tenure in Brazil, Reichert became interested in the music of the choro players and incorporated it into his compositional style. According to the 1900 edition A Biographical Dictionary of Musicians by Theodore Baker, Reichert composed “difficult music for the flute.” He died in poverty and is buried in Rio. |

Analyze First

Part of the pedagogy of learning vocalizes is to transpose them into all major and minor keys by ear without the music. In order to do this, analyzing the harmonic chord structure makes the process faster.

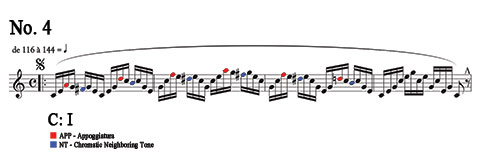

This entire vocalise, like many, is built on a I chord – C, E, G. The non-chord tones are identified as:

Red notes – Appoggiatura (approached by leap, resolved by step)

Blue notes – Chromatic neighboring tone (a second below two chord tones).

M.A, Reichert, No. 4:

Steps for Practice

1. Play the entire vocalise to become familiar with the notes.

2. Play again, substituting a rest for the circled non-chord tones. Count carefully as this is more difficult that it appears to be.

3. Play again, placing a fermata on each circled non-chord tone.

4. Play again in its entirety listening for the non-chord tones.

5. Play chunked in the traditional Kincaid manner, 1 rest, 2341 rest, 2341 rest, etc.

6. Play chunked (Early music style) 1234 rest, 1234 rest, etc.

7. Chunk (note-group) three notes, rest, five notes rest. Play the three-note chunk forte and the five-note chunk piano.

8. Chunk by eight notes followed by a rest.

9. Chunk by measure followed by a rest.

10. Chunk by two measures followed by a rest.

Continue this process through the other 23 keys of this vocalise.

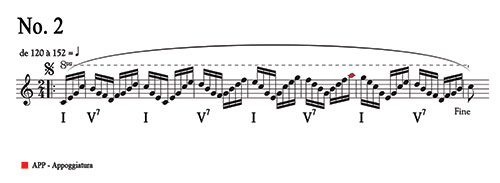

Next, take a look at M. A, Reichert, No. 2:

This vocalise alternates between a I chord and a V7 chord. Interestingly there is only one non-chord tone and this is the A (an appoggiatura) in measure 5. Try these note-grouping steps and notice how individual sounding they each are.

1. Play entire vocalise to become familiar with the notes.

2. Play chunked in the traditional Kincaid manner, 1 rest, 2341 rest, 2341 rest, etc.

3. Play chunked (Early music style) 1234 rest, 1234 rest, etc.

4. Chunk by measure (the pickup will be a separate chunk). Notice that the whole measure is an arpeggiation of either a I chord or a V7 chord. Knowing this simplifies memory.

5. Chunk by eight notes

6. Play entire vocalise listening for the individual chords and the appoggiatura.

A Five-Step Practice Routine for the Two Vocalises

This five-step practice routine was shared with my Brigham Young University-Idaho flute studio by Erich Graf, retired Principal Flute of the Utah Symphony. It is surprising how well this solves technical problems as well as helps the flutist see a melody or vocalise in a new light.

1. Chunk by three notes, slurred followed by a rest. Go slowly at first to be sure that you are accurate.

2. Omit the first note, and chunk by three notes, slurred followed by a rest.

3. Omit the first and second notes, and chunk by three notes, slurred followed by a rest.

4. Play in a dotted eighth followed by a sixteenth rhythm single tongued. (When playing this rhythm, say, Day, To-Day, To-Day etc.)

5. Play in a sixteen followed by a dotted eighth note single tongued. (This rhythm is also known as the Scottish Snap.)

Repeat these five steps several times each time increasing the tempo until you can execute this quite fast. In doing this you may see the notes in a different pattern than you originally did and that is the wonderful benefit. If you are using this for technical learning rather than melodic study, repeat several times for a week or more.

These concepts may be applied to etudes and specific phrases in repertoire. Not only will you have new ideas to use in shaping the phrases, but this exercise is a marvel for learning or crunching new notes.