After years of training in all aspects of running a band program, the anxious excitement of newly graduated instrumental music education majors is only exceeded by an exhale of relief when that first job is secured. However, reality soon sets in as the schedule reveals that in this school, the band director also teaches choir. Even if an instrumentalist sang in a choir in college or took a class in choral methods, it is certain there are areas where the seemingly comprehensive classes completed in preparation to run a band program did not provide the same skills for directing a choir. However, the choral classroom does not have to be overwhelming to an instrumentalist.

When switching from an instrumental to choral rehearsal, some of the areas of greatest anxiety are tone development, diction (especially foreign languages), a methodical approach to teaching sight-singing, and selection of choral literature. Many may consider the greatest area of concern to be developing a healthy tone, as students only have one instrument and damage could have life-long consequences.

Tone Development Through Warmups

The objective of warmups should be to teach healthy vocal technique. Many directors see the purpose of warmups as actually warming up the voice, however, in an amateur choir, this should be seen as a wonderful by-product rather than the goal. When warming up the voice is the objective, warmups are often eliminated because of rehearsal time constraints, especially in ensembles like church choirs that only meet once a week and have to perform new music weekly. For most inexperienced singers, the choral director is their only voice teacher, and habits formed in these ensembles will have lasting effects. James Jordan, professor and conductor of the Schola Cantorum and Williamson Voices at Westminster Choir College of Rider University, believes that if you fail to have a regimented warmup sequence, the rest of the rehearsal will be spent fighting problems that could have been addressed by a quick five- to seven-minute warmup. Therefore, it is possible warmups are the most crucial part of the rehearsal.

Warmup Sequence

There are many different philosophies regarding what should be included in a warm-up sequence. The suggested order is deconstructing the body; breathing exercises; head voice development; range extension upward; vowel unification, balance, or ear training; agility; and range extension downward. This order has been adapted from the warm-up philosophies of Charlotte Adams, James Jordan, Kenneth Phillips, Jerry Blackstone, Jeff Johnson, and Lori Hetzel.

Time constraints may require combining several of these categories. In a fifty-minute rehearsal, picking a warmup that addresses range extension upward and agility simultaneously, and another that combines range extension downward and vowel unification, drops the sequence from seven steps to five.

When looking at these different areas, many scholars suggest the use of gestures to help singers achieve the desired result. So much of singing deals with muscles that are either involuntary or cannot be seen that a movement reinforcing the desired outcome is quite helpful. Janet Gavlan said, “If the body goes, the voice will follow.” While this may feel uncomfortable for everyone at first, the benefits surpass the initial awkward period. Therefore, each exercise below will also contain a recommended motion.

Deconstructing The Body

The term “deconstruction of the body” comes from James Jordan; his premise is that singers enter the choral rehearsal with terrible posture and improper use of the voice through daily activities. Students in public school may have been sitting at a desk all day, yelling to friends in the lunchroom, tense from a stressful test, or upset because of a breakup. All of these activities harm the singing voice. The sound of the choir can be transformed by eliminating tension and correcting poor posture. Below are several exercises to try in rehearsal.

Stretching

Have students lift hands above their head and then stretch up, over to the left, and then back to the right. Then, students should bend over and dangle hands and head while rounding out the back. Slowly come back up, thinking of each vertebra stacking on top of the other. Another stretch is to push the arms out in front of the body, rounding the shoulders forward to feel a stretch between the shoulder blades. Students can also clasp their arms behind the back and pull shoulder blades together, feeling as if the sternum is opening.

James Jordan suggests using mental imagery for fun ways to stretch the body. This can be quite effective for younger singers and adds a fun element to warmups. One example is to have students pretend they are going swimming. Jump in the pool, swim down to the end of the pool, backstroke to the other end, climb out of the ladder, get your towel, and dry off.

Massage

This is probably the favorite of many singers. Make a line and massage the shoulders and upper back of the singer in front of you; then scratch and karate chop before turning the other way and repeating the sequence.

Self-massage of the face and neck is also useful. Have students massage where the jaw comes together and down the side of the neck. Tension in these two areas can easily be heard in singing and will cause problems in the singing voice.

Breathing Exercises

Techniques used in instrumental training can be quite effective, but some may create unintended tension in the singing voice and should be avoided in choral rehearsals. As mentioned in massage activities, excess tension in the neck muscles is detrimental to tone development. Also, sound in the inhalation caused by tension in the neck should be avoided at all costs. These exercises can be helpful in teaching proper breathing while avoiding unwanted tension in the upper third of the body.

Showing what the body does

James Jordan uses four motions while inhaling to show the singer what the body is doing while taking in a breath. This can be useful for singers who are inverting their breath by raising the chest and shoulders and bringing the stomach inward during inhalation.

Start with hands resting to the side of the body. Bring forearm up to a 90 degree angle from the upper arm, similar to a conducting position. When inhaling, allow the forearms to move out while shoulders and chest remain low and do not move upward. This represents your intercostal muscles, which allow your rib cage to expand.

Place your hands in a dome at your chest (imagine making a rainbow with your hands). During inhalation allow the hands to go to a flat, horizontal position without moving any other parts of the arm. This represents the diaphragm, which goes flat to allow your lungs to take in air. You do not support from your diaphragm; that is a common misconception.

Place your hands at your belly button with palms facing inward and middle fingers touching (imagine hugging a ball). Inhale and allow hands to go straight out in front of the body. This represents the stomach expanding outward.

Place your hands at your belly button with palms facing the floor and middle fingers touching. While inhaling, allow the hands to press toward the floor with palms still facing the floor and middle fingers touching. This represents lowering of the pelvic floor.

Inhalation and exhalation at different rates of speed

Have students focus on keeping tension out of the neck, jaw, or tongue throughout this process.

The first exercise is to inhale for a specific number of beats and then exhale for a specific number of beats with no sound. Placing hands on stomach can help remind students to expand throughout the inhale. Hands around the side of the waist (thumb facing forward with the other four fingers vertically stacked toward the back side of the waist) is also useful and you can remind singers to keep rib cage expanded while exhaling. It is ideal to work down to a one-beat inhalation with no tension as this is where tension often occurs in the music.

Inhale for a specific number of beats and then exhale for a specific number of beats on a sustained consonant such as s. Use any of the previous hand motions for kinesthetic reinforcement. Make sure when using the sustained consonant, the pressure does not cause tension in the neck. When transferred to singing, this will produce a pushed sound and can have a detrimental effect on intonation. On the sustained release, encourage singers to keep rib cage expanded as long as possible.

Vary the counts for each inhalation and exhalation; also, try different consonants.

Development of Head Voice

Singers who choose to join a choral ensemble often have experience singing other genres of music. Whether they enjoy singing along with the radio to their favorite pop star, belting Broadway ballads, or singing Gospel music at their church, it is possible they will enter the ensemble with a different concept of sound than is needed for choral singing. Helping singers to develop versatility in space, vowel shape, and mixture of head and chest voice can help them perform well in multiple genres of music.

One of the most common problems of inexperienced singers is taking the chest voice too high. Helping students mix the head and chest voice is essential in creating a balanced choral sound. The opposite would be a very robust chest voice, then a complete break followed by a light head voice.

Many experts believe the easiest way to accomplish this is by making sure the first vocal exercise of the day is descending, beginning in head voice and allowing the mix to occur naturally over time. Kenneth Phillips, Professor Emeritus at the University of Iowa, recommends a top-down approach for children, starting at C5 and descending to C4. When working with a mixed choir containing changed male voices, consider beginning with an exercise in F major, starting on the fifth scale degree and descending stepwise to tonic. (C-Bb-A-G-F) This would mean starting at C5 for women and C4 for men. Some choral directors prefer beginning in D major, however, there are many singers who can still sing that A in chest voice. Ee (as in meet) and ay (as in chaos) vowels are effective at producing a “spacious, high, and forward” sound.

Below are several exercises to help inexperienced singers find their head voice and learn to mix it with their chest voice, eliminating an obvious break.

Hung-ee

Make a C shape with your hands, turn the fingers toward the ground, and place your four fingers against your cheeks. This motion will help emphasize the vertical space needed for choral singing with soft palate high and tongue relaxed with the tip against the back of the bottom teeth. Have singers imagine the inside of their mouth looking like a rectangle with the long side being vertical and the short side horizontal.

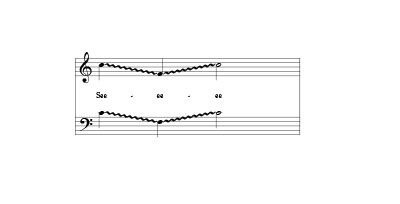

See-ee-ee

Make a shallow V with your hands. Your middle fingers should touch just at the top of the lip, while the rest of your hand should run along the bottom of your cheeks. Tell singers to imagine the sound originating above the hands rather than below. This helps produce the high sound Jordan mentions. Getting the sound to resonate in the nasal cavities is not an easy concept to teach, but this motion may help over time.

If possible, separate men and women into different ensembles. This allows the director to focus on the differences between male and female voices. When working to develop the proper placement and buzz in the sound, Jonathan Reed, Professor of Music and Associate Director of Choral Programs at Michigan State University, suggests starting the men in falsetto and descending. Men tend to carry too much weight as they ascend, so starting in falsetto and stressing the feeling of less weight and pressure when they get below middle C can aid males with the transition into full voice. When doing this, remain in F major, but begin the male students at C5, rather than C4.

Bee-bee-bee-bee-bee

Position your pointer finger directly between your eyes and shake it forward with each new pitch. Imagine someone saying you did something wrong and shaking their finger at you while speaking. This motion reinforces the forward position Jordan is referring to. Many voice teachers also refer to singing in the mask. This creates a mental image of the sound vibrating in the areas where your face is covered by a mask, your eyes and cheeks (nasal cavity). Men will often swallow the sound, especially as they descend, causing the pitch to go flat. Encouraging them, as well as women, to think upward and outward as they descend can help prevent swallowing of the sound and improve pitch.

Upward Range Extension Exercises

Learning to access the higher register of the voice requires a systematic approach, just as with an instrument. Many women will say they are altos and cannot sing high, but this is false. Men, meanwhile, unnecessarily switch to falsetto earlier than is needed as they ascend. The most common mistakes when trying to sing high are caused by improper support through the core: the larynx will rise and tension with the tongue, jaw, and neck will often occur. This produces a pinched sound rather than a free, vibrant tone quality throughout all registers. There are several important concepts to consider when helping students access their high register.

Vowels must be modified as the singer ascends. Women should modify to an open vowel as they approach the top of the staff, and should use an ah (as in father) above the staff. Closed vowels like ee and oo (as in food) should be avoided in their unmodified state higher in the range.

Men should move to a closed vowel before modifying to an open vowel. Tenors should move toward a closed vowel (ee or ay work well) around Eb4, then open up toward an ah as they go higher. Basses should move toward a closed vowel (ee or ay) around Bb3, then open up toward an ah as they go higher.

Consider stopping at G5 (women) and G4 (men) or lower when beginning range extension exercises. If tension can be seen or heard, stop earlier and don’t go as high the next day. When G is free from tension, gradually add a half step higher with the aim to reach C6 (women) and C5 (men) once daily during the range extension exercise.

Because of the changes in middle school voices, consider stopping with G5/G4. Cambiatas (boys in the midst of the voice change) will often have a range that goes from about G3-G4 for changing tenors and D3-D4 for changing baritones. This is general – some may not have this large of a range – and should be considered in range extension exercises.

Keep young baritones below C4 unless it is apparent they can sing it without straining. Once you get high enough to be completely in their falsetto (possibly F4), allow them to sing higher to not lose the ability to sing the notes they had before the voice change. They may struggle with their voice cracking and also may struggle to find their head voice. Consider working from their falsetto downward to find a heady tone. They may still have cracking, no transition from falsetto to full voice, and possibly note gaps.

Use a descending motion when ascending. This may seem counterintuitive; however, the descending motion can activate the core and possibly keep the larynx from raising.

James Jordan recommends using arpeggios performed at a fast tempo. This works well as long as students are engaging the core while singing. Start on Bb3 (girls) or Bb2 (boys) for exercises spanning an octave or more (ex. 1-3-5-8-5-3-1), then repeat the exercise ascending by half steps.

Below are several exercises that can help with range extension. Consider starting with exercises spanning only a fifth until singers are more experienced. D is likely to be a good starting note for these exercises.

See-ee-ah-ah-ee

.jpg)

Have students squat down without allowing torso to lean forward or back and pretend to shoot a basketball.

Zee-ah-ah-ah-ah-ah

Have students swing their hands out to their sides just below their waist on the high note as they do a plié in second position (legs turned out with feet pointing in opposite directions and heels at least shoulder-width apart). The key to a plié is to keep the upper body from dipping forward or back. Modify the pose so toes face out at a 45° angle rather than 90°.

Vowel Unification, Balance, Ear Training

Vowel unification, balance, and ear-training are all important to a choir’s development, but time constraints may necessitate working on all three in one exercise. Using the current music to create exercises can help isolate a problem without all the other variables. For example, if the choir is singing in Latin but struggling with vowel unification, you could create an exercise using the following pure vowels used in Ecclesiastical Latin: ah (father), eh (debt), ee (feet), aw (lawyer), and oo (food).

Nee-neh-nah-naw-noo

Place hands in front of stomach pretending to hold a ball. One hand should be on the bottom of the ball and the other on top (not the sides). This helps to create a warm, round sound that makes unifying vowels easier.

Insert a chord with vowels

This exercise allows singers to listen for both vowel unification and balance. Basses and sopranos can sing the tonic, tenors the fifth, and altos the third. Have the students move the chord up or down by half steps a cappella – or change the chord quality – and this exercise will also work on ear-training and intonation.

Many directors have specific hand motions for each of the five Latin vowels. The motions below come from Jeff Johnson’s Ready, Set, Sing.

Ah: make a C with the right hand, turn to where the fingers point downward, and place your four fingers next to your cheek.

Eh: put the thumb and pointer finger on either side of your lips to remind students not to spread this vowel.

Ee: put the thumb and pointer finger together, and with tips of fingers toward your face, pull forward from between the eyes.

Aw: point the tip of the index finger toward the mouth and draw a circle around your lips.

Oo: put the thumb and pointer finger together, and with tips of fingers toward your face, pull forward from your lips as though holding a strand of spaghetti.

Agility

Agility takes considerable time to develop, and there are several approaches to consider. Starting simply with inexperienced choirs is crucial. Something as easy as a staccato arpeggio on see-hee-ha-ha-ha, encouraging them to think of their stomach like Santa’s bowl full of jelly, can help train singers to bounce rather than sing an exercise completely legato. Singers can place their hands on their stomach to feel the difference between this and a legato exercise. As singers advance work to take away the h articulation and coordinating the breath and pitch starting at the same time.

James Jordan encourages directors to teach students how to sing in a martelé style. Starting slowly, singers will allow a bounce of the stomach with each pitch, using a d at the beginning of each note to help with the articulation. If breath support has been taught by bracing in the stomach area, this concept is even more difficult to teach, because flexibility is needed from the core muscles. Once singers are coordinating the muscles with the change of pitch, remove the d, working to align the pitch change to the stomach on only the vowel. Make a fist and punch out from the stomach area, just in front of the belly button, with every d. The next step is to keep the d only on the first note of each triplet. Then, remove all consonants. If singers struggle to coordinate the onset of sound between the voice and the breath, it is helpful to have them think of adding an inaudible h before the vowel.

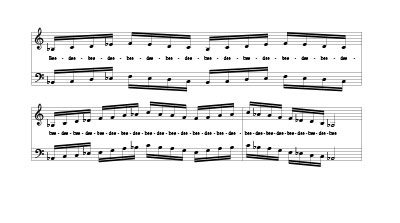

Another technique used for melismas in music, like “For Unto Us” from Handel’s Messiah, is to add two different syllables to the notes of the run. Bee-dee-bee-dee (below) works quite well because the b is produced with the lips and d uses the tongue. Jerry Blackstone has also taken the concept and made it into a warm-up for male voices. Not only does it work on agility, it requires the male voice to move easily in and out of full voice, head voice, and falsetto at a quick pace.

A good visual cue for this is to move hands in a circular motion in front of the stomach, thinking of tossing a beach ball in the air.

Developing agility can be compared to learning to play martelé bowstrokes. Allow a bounce of the stomach with each pitch, using a d at the beginning of each note to help with the articulation.

The next step is to keep the d only on the first note of each triplet.

Finally, remove all consonants. If singers struggle to coordinate the onset of sound between the voice and the breath, it is helpful to have them think of adding an inaudible h before the vowel.

Relaxation Exercise

It is helpful to end the warmup time with a relaxation exercise. Charlotte Adams provides several that are quite effective. Starting in D major and descending until students reach their lowest note is not only helpful in relaxing, but gives basses a chance to show off the low end of their range. When doing this, encourage students to drop out when it is too low rather than push. Middle school girls do not need to venture very far below middle C4; elementary students should not go below this note at all.

When descending below the staff modify the vowel toward an open syllable for lowest notes. Ah works well. Use a motion that brings the sound forward and up as they descend to prevent flatness and swallowing of the sound.

One of Adams’s relaxation exercises that works well for this process is bumm-biddly-biddly-biddly-bumm (top of next page). Have students bounce on toes, put hands beside cheeks, and pull upward with each note.

Conclusion

Developing a beautiful choral sound is a lifelong pursuit, and being on a choral podium is challenging for even the most seasoned conductors. However, with a systematic approach to developing a warm, tension-free sound, the well-developed assets a skilled band director brings into the rehearsal provides the potential for a highly successful choral program at any level.

Bibliography

Daily Workout for a Beautiful Voice by Charlotte Adams (Santa Barbara Music Pub.,1991, DVD).

Evoking Sound: Body Mapping Principles and Basic Conducting Technique by James Mark Jordan and Heather J. Buchanan (GIA Publications, 2002).

Evoking Sound: The Choral Warm-up: Method, Procedures, Planning, and Core Vocal Exercises by James Mark Jordan and Marilyn Shenenberger (GIA Publications, 2005).

Glossary of Ballet, Wikipedia (from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

“Movement and the Choral Rehearsal: Part One The Use of Movement in the Choral Rehearsal” by Janet Galavan. From In The School Choral Program: Philosophy, Planning, Organizing, and Teaching, ed. Michele Holt and James Mark Jordan (GIA Publications, 2008).

Ready, Set, Sing! by Vance D. Wolverton and Jeff Johnson (Santa Barbara Music Pub., 2001, DVD).

Teaching Kids to Sing by Kenneth Harold Phillips (Schirmer, 1992).

“Working with Male Voices” by Jonathan Reed. From In The School Choral Program: Philosophy, Planning, Organizing, and Teaching, ed. Michele Holt and James Mark Jordan (GIA Publications, 2008).

Working with Male Voices: Developing Vocal Techniques in the Choral Rehearsal by Jerry Blackstone (Santa Barbara Music Pub., 1998, DVD).