Improvisation can be easily learned through bite-sized, sequential development. However, the greatest information in the world, given to students in the wrong order, will only produce glassy-eyed looks. Teaching scalar improv too soon will result in students improvising mostly with scales, and putting changes down in front of students will produce arpeggio improvisations in which the chord is the end, not the means. In addition, students accustomed to using scales to improvise rarely have ears for melody, and they also eventually plateau in their improvisation development; students have some early success but eventually start playing the same ideas over and over. Getting them beyond that can be difficult.

The ideal choice is to begin teaching improvisation by paraphrasing melodies. This is using a liberal amount of the melodic line and tweaking it by changing rhythms and adding some scalar material to connect phrases. For example, on a phrase that has a long note in the melody, you could use the length of that note to weave in a scale pattern. It is still essentially the tune itself.

In the early days, this is how jazz players improvised. The harmonies in most 1920s tunes are occasionally quirky, but usually transparent, and in Kansas City in those days, it was mostly blues. Virtually everyone played by ear. Some Kansas City bands had no physical book at all. At one point jazz musicians were judged in part by the number of tunes they had memorized. Non-diatonic chords are often passing chords. They had the tune to work with and only a short amount of time, because in early recordings bands were limited to three minutes on a record side. Generally, a player would get only one or two A sections or a bridge and an A section, and that would be it. This meant they could not explore far away from the melody, at least on recordings.

Jazz moved away from the melodic paraphrase style of improvisation as arrangements became more complex, leading to great dependence on what was on paper. As a result, people used the melody as a basis for improvisation less frequently. Some of it is just the evolution of the art form, but there was a generation of players who, if told, “Summertime in D minor,” could play without any music. There are still some players who do that, but not many young players. We almost lost this art, but in recent years, ear playing has made a comeback.

Playing by ear is the foundation of melodic paraphrase. Antonio García wrote a book, Cutting the Changes, using these principles. The first part of the book contains only melody and lyrics. Chords are in the back of the book. One year at the Midwest Clinic I expressed my admiration for the book and asked him what inspired him to take this tack. He said, “People have been doing this (having no chord changes in front of them when they learned tunes) for 90 years.”

Don Doane, the great Maynard Ferguson/Woody Herman trombonist and jazz teacher, used this as the foundation of his approach, only his version was pared down even more. You learn everything by ear. This method is also espoused by Dave Demsey of William Patterson University, who says, “When you read it, it doesn’t stick.” This has been my experience. One student I worked with was a good player but just not progressing. It was difficult to get him to improvise based off of the tune, because when students see chord changes, that is what they use. If they don’t have them, they can’t run to them.

In the jazz improv course I taught this spring, we learned everything by ear. To teach tunes, I played a phrase on my horn, and students played it back. We could learn a tune by ear in roughly 15 minutes. I picked easier tunes they would know, such as Summertime and When the Saints Go Marching In. We learned more than ten tunes by ear, getting as advanced as Take the A Train, and the more that we did it, the faster students became at it.

John Cooper wrote a book called Linear Transitions, which is about using a number system to learn tunes and improvise. We tried it with When the Saints Go Marching In. I gave students the number of where each note fell within the scale (1 3 4 5). Another tune we learned was Moten Swing. This chart lent itself well to the numeric method because of the flat 3 in the melody and the modulation of the bridge from Ab to C major. We played through it, talking through the form (AABA). This helped shorten the time needed to learn a tune. We still used imitation primarily, but we did a bit with numbers, particularly on bridges, to reinforce intervallic skips. At the same time you practice melodic recognition, you can also improve ear recognition of the chordal aspects.

When students started to improvise off of these melodies, solos sounded more natural and less stilted, because students were less hung up in the vertical aspects of playing. If all you have is the melody, then all you can do is play with the melody. I have talked to musicians who play this way. A man who coached combos here for a number of years is an engineer who taught himself jazz and plays everything by ear. When he solos, there is almost never a wrong note. I asked him if he saw the chord changes in his mind while he was playing, and he said, “No, usually I don’t even know what chord I’m playing over, but I know what will sound good.” I bring him in on occasion to play a couple choruses of A Train. He will whip through it with no missteps of any sort, and students’ jaws are right on the floor. If the focus is on chord changes, you will be thinking in terms of vertical realizations of the chord symbol, meaning making sure you’ve included the right notes for the chord. If you don’t have that at your disposal, you can start to think about creating longer phrases.

Even without having changes in front of them, students frequently play in tiny cells at first; they will get an idea and try to play around with it that way. I then asked them to make two-bar phrases out of their ideas, which pushed them in a linear fashion. If you can get them to think in a one or two bar linear phrase, then the next step is to turn that into a four-bar idea.

When students get to the point of developing a four-bar idea, then they should look at the music briefly, find the chord in that fourth measure, and pick a destination note. Picking a destination note gives students a sense of where the harmony is and starts them thinking about the journey rather than the destination. With vertical thinking, the tendency is to think of every measure as a destination, and that should be avoided.

I like to use the third of the chord as a destination, because I read somewhere that 75-80% of all resolutions are to the thirds of chords. If you listen to Miles Davis in his Porgy and Bess era, there are frequent resolutions to thirds. So when it comes time for students to think in four-bar ideas, have them pick the third as a destination note. The second most common choice is the seventh. When working in this way, students’ mindsets change. Melody is not vertical, and if you want to improvise melodically you have to have a grasp of the idea of horizontal movement; this concept is extremely important.

The second step is the scalar approach, which I sometimes call the Lester Young approach. In the late 1920s and 1930s tenor saxophonist Coleman Hawkins was the king of vertical (chordal) playing, which relies a great deal on arpeggios. His rival, Lester Young, was the polar opposite. Young rode a horizontal approach that created lines of great fluency and beauty. He had a knack for finding pretty tones, particularly on the sixth scale degree. Lester Young’s developments were so revolutionary because he was one of the first to think horizontally. Jazz players have to get to the chords eventually, but this is why many of the players who focus exclusively on arpeggio improvisation to be more clinical. No one ever accused Lester Young or Miles Davis of being clinical.

Miles Davis’s music was extremely lyrical in the 1950s, and that evolved into the modal playing that he did in the 1960s, in which, if you have two chord changes in a tune like So What, you have to think horizontally. You can’t think vertically because there is no vertical to think about. This is the root of much of today’s pentatonic playing.

We start with the melodic line, but when students start to play with it, we have them connect ideas with the pentatonic scale. Antonio García uses the major scale first in improvisation, because this is something students will know. I prefer to start with the pentatonic, which is the same scale with two notes removed; it is worth noting that the remaining notes are all consonant. The advantage of starting improvisation with the pentatonic over a major scale is that you don’t have to worry about students sitting on dissonant fourth or seventh scale degrees. We move into major scales fairly quickly after that, dealing with it fairly lightly. If the melodic aspect is emphasized, students do not immediately start playing only scales when they improvise. If students are grounded in melody, then they rarely stray too far from it. If they do, you can always stop them and say “use scalar patterns or pentatonics to connect, but don’t make that your focus.” It is an easy fix.

The scalar and horizontal approaches are particularly helpful in the A section of 32-bar tunes, as well as with modal charts. In the latter, the static harmonies demand a strong melodic approach. In AABA tunes such as Moten Swing, we teach the A section as an entity, and then move on to the bridge. The tune is in Ab with a bridge in C. In the A section you can have students use a major pentatonic scale or the known, the major scale.

My teaching shifts slightly from the straight linear aspect once you get to the bridge. With a chart like Moten Swing, the bridge is the time to go to the printed page and a chordal approach. Students will need a strong sense of where they are harmonically, because the natural tendency is to play the whole tune like it is in one key. This is why the best way to start chordal improvisation is with memorization of roots. I have students create root solos, which are rhythmic licks using only the root of the current chord.

I started using root default after years of hearing students play over blues but miss the IV chord. They put a blues scale over the entire blues progression without regard for harmony. The IV chord is harmonically a startling point in the blues, and no one should simply skate over it as if it didn’t exist. However, many young players do this, assuming that the entire blues scale works throughout the blues. To counter this when teaching blues, I define the I chord with something that isn’t blues, at least when students start learning it. Rather than teaching the blues scale or minor pentatonics, we teach major pentatonic scales, so the I chord at the beginning does not have a lowered third. At the IV chord, give them one note, and when they get to measure five, we’re going to play the root default (the root of the IV chord). At the ninth measure, if this is a V chord, we play the root there too. This way students have concrete instructions for the harmonic signposts in the blues and are not playing like there are no chord changes. I have found this works well.

Interestingly enough, these root solos often reemerge in later solos. Students understand that root default is an important part of vertical realization. That knowledge becomes important because the point of a bridge in a tune is the shifting harmonies. Bridges of tunes demand special treatment. This is especially true of circle-of-fifths bridges, where you teach them that you can make the entire bridge with four notes.

I’ll go into my improv class and say we’re going to play Tenor Madness, blues in Bb. For your first chorus, I want you to do root defaults, and they know what to do. After that, I let them do what they want, but they come back to root defaults from time to time. The same is true with guide tone lines over circle of fifths bridges. Students aren’t going to play these all the time, but it will inform their improvisation choices, and they do know what is in the chords, which is the most important thing. The harmonic knowledge is important but should not be the prime focus of what you do. Harmonic knowledge should be one tool in the arsenal.

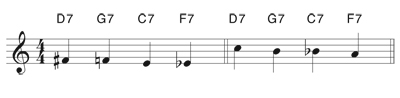

Arpeggios are the last thing I teach, and with these, I initially avoid recorded tracks. Recordings are good tools, but what I’ve found is that when students are learning arpeggios for improvisation, sometimes a recording goes by just a little too quickly. Students become so concerned with just keeping up that they get vertically discombobulated. Often, the entire solo ends up looking like this:

To make it easier on students, remove tempo and let students be thoughtful about what they are playing. If the first chord is C7, have them focus on really hearing the chord rather than worry about keeping up with the track; students should burn the sound of 1, 3, 5, flat 7 into their minds. When that is fluid, then it can be put back into context. Ultimately, for this knowledge to be helpful, it must be memorized. Only then can a set of changes be approached in a complete, in depth fashion.

Improvisation is perhaps the greatest creative outlet and whole mind builder in education’s arsenal. It deserves the best we have to offer, and in improvisation, teaching the steps in the correct order is everything.