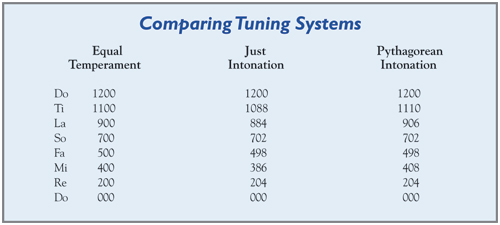

When asked, students might say that a tuner indicates whether a note is in tune, but this is incorrect. Tuners actually show deviation from the equal temperament system. Students should strive to get as many notes as possible close to zero, but what determines whether someone is in tune is getting rid of beats in the intervals when playing with others. The point at which these beats are eliminated is called just intonation.

Practicing Tuning

A good daily tuning exercise is Carmine Caruso’s six-note exercise, although I extend it to 13 notes, from written C4 chromatically up to C5. Students can use any notes in a comfortable range for this exercise.

I recommend doing this exercise with the tuner on early in each practice session. Although it is good to vary how you warm up and practice, this tuning exercise is the one part of my routine that never changes. It takes about two minutes, and from this exercise I can tell whether I might have difficulty with intonation on any given day. Sometimes the room temperature can cause flatness or sharpness, but other times my embouchure might simply be stiff from working hard the day before. When consistently flat, just push the tuning slide in rather than fight it.

Students can also play through this exercise as a part of warming up before rehearsal. Many tuners can pick up just one person, even in a noisy room, and it is better to take care of tuning before rehearsal starts.

Students should record themselves and review the tapes to see how in-tune they are. I am often my toughest critic, as is true for many people, and listening to a recording will make apparent any poor intonation in my playing. I recommend recording to check pitch at least once a week.

Twice a year students should survey every note on their instrument with a tuner to see where the natural center of each pitch is. Every note on an instrument has a center, a pitch where the note is naturally most resonant. Ideally this is at zero on a tuner, but that is not always the case. I recommend doing this in spring and fall, because the temperature of the room should be fairly consistent; doing this in spring and fall eliminates climate as a possible reason for a change. Any changes noticed should be changes in the ability to control the instrument.

A musician may need to bend the sound, but to know which way to move off the center of the sound, it is necessary to know where the starting point is. For example, on a trumpet, E5, Eb5, D5, and C#5, the notes played on the fifth partial, are usually flat. If one of these notes is the fifth of a chord, the player will have to bend the pitch up quite a bit more than the usual two cents to be in tune. When playing, students should be especially aware of the notes that are difficult to get within five to eight cents of zero on a tuner.

Students should work on coming in right on the sweet spot of each note; sometimes a student may slide into the center of a pitch because articulation bends a note sharp or flat. I practice this by playing a scale in every key every day.

Use a drone to practice bending pitch. This is one of the best ways to learn the pure widths of intervals, the point at which there are no beats in the sound. In fine tuning, there will be considerable playing that is slightly off-center, as much as 16 cents sharp for the third of a minor chord to 31 cents flat for a minor seventh. The ability to bend the pitch even further than these limits ensures that these extremes are easy to hit. Musicians should strive to be able to bend the pitch 20-40 cents on any note at any dynamic. I recommend playing both intervals and arpeggios with a drone.

Every instrumentalist should have a bag of tricks for changing intonation. Trombonists have the easiest time of this; their main slide is easy to use for fine tuning adjustments. As a horn player, I was taught to adjust the embouchure looser for flatness or tighter to be a bit sharper. Changing the tongue or jaw position can also change intonation. Alternate fingerings are another way to change pitch, as some fingerings are flatter or sharper than others. Hornists can also adjust the right hand; adjusting how cupped or flat it is will affect pitch as well.

Some notes on woodwind instruments are extremely inflexible. For a major third, the distance between those two notes should be lowered 14 cents. However, this doesn’t always mean that the person playing the third should lower his note; it may be a difficult note to adjust on his instrument. The two players should communicate about such things, and if the player with the third can only lower the pitch seven cents, the other player should bend the root sharp to make up the difference. This may be the only way to eliminate beats.

Although checking an instrument’s tendencies is best done in temperate weather, students should also learn what happens to their instrument during temperature extremes. There were studies done on this back in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Tubas and horns are most affected by temperature, followed by trombones, flutes, and trumpets, with slightly less change in clarinets, oboes, and bassoons. Horn and tuba players should remember that temperature affects them more than it does other people; in a hot room they need to pull the tuning slide out.

Tuning Chords

Take chords apart to tune them. The first step is tuning the root, which should be done with a tuner. Tune the lowest octave first. Starting with the bottom octave makes it easier for everyone to hear how they fit in. While tuning chords, students should play at mp-mf regardless of the dynamics written in the music.

Tuning a chord should always start with the root, regardless of which instruments play it. If a major chord is in first inversion and the root is primarily in the highest-pitched instruments, tune these first. If the third is in the lowest instruments, they should tune last. This forces the low woodwind and brass players to think about pitch more than they may be used to. If tubas play the D in a Bb chord, starting with tuning that D to zero on the tuner is going to throw the pitch of the entire band off, as the instruments with the root will have to play 14 cents sharp for the chord to be in tune.

If the low players adjust poorly, it can throw the medium- and high-register players off quite a bit. An error of four cents on a tuba playing the third of a chord doubles the beats per second with every octave. If that third is doubled or even tripled, the players in the upper octaves, if they want to tune a good octave with that tuba player, will have to double the beats. The tubas might only be off enough to create a few beats per second, which will not sound like a big problem, but an instrument three octaves higher will have eight times as many beats per second.

When the root is in tune, add the fifth. If directors want to hear this note alone, it should not be at zero on the tuner; ideally it will be two cents sharp, a distance that few tuners can measure well. Turn the tuner off when the root is in tune. Again, start with the bottom octave.

When the fifths are pure, add the thirds. For a major triad, the pitch should be lowered by 14 cents, and for a minor one the pitch should be raised 16 cents. After a chord is in tune at a medium volume, have students play it again at the written dynamic.

I have my students sing frequently; this is the best way to develop students’ ears. Sometimes I tune chords using these steps, but by having students sing rather than play.

The simplest chords are the most difficult to tune well. Chords with 7ths, 9ths, or 11ths are not as worrisome as the simple ones. Often, tuning dominant sevenths is an artistic choice; on a seventh chord it is sometimes acceptable to leave things a bit unstable. That may even be the composer’s intention. To eliminate the beats, it is necessary to lower a dominant seventh by 31 cents, but if the seventh appears in a middle voice, lowering it 31 cents will bury the note. Conversely, if the seventh is in the highest voice, lowering it by 31 cents might draw way too much attention to the note; sometimes it is better to leave some of the beats in.

Wind Players in Orchestra

Orchestras use Pythagorean intonation, so it is beneficial to know the tendencies that strings have; they use this system because it gets rid of beats on their open strings. String players keep the same distance between do-re and re-mi, which pushes thirds higher than they would be in a band. Knowledge like this can help students adjust in advance.

As an example, the orchestral version of Shostakovich’s Festive Overture has a section in which a solo horn plays a melody along with the cellos. Knowing the characteristics of the Pythagorean system will help a hornist play with a cello section better; in this example the hornist, perhaps used to lowering thirds, will have to raise it to match what the cellos are likely to do.

Each member of an ensemble should always assume he is the one who is wrong and adjust when something sounds wrong. The musicians who adjust the fastest are the ones who develop the reputation for playing in tune.