Harry Begian grew up in Dearborn, Michigan, and when he first heard a band in school, he was so enthralled with the sound that he took up the cornet. He earned a B.A. from Wayne State in 1943 and briefly taught at McKenzie High School in Detroit. He was soon drafted and played in the 180th AGS Band of the U.S. Army.

After military service ended, he pursued a master’s degree at Wayne State and then became the band director at Cass Technical High School in Detroit. He developed an outstanding program and was invited to perform at the Midwest Clinic in 1954 and 1961. Along the way he earned a doctorate from the University of Michigan and became director of bands at Wayne State University. The director of bands position at Michigan State University opened in 1967 when Leonard Falcone retired, and Harry Begian took over.

He stayed there for three years and then took a similar position at the University of Illinois in 1970 where he stayed until his retirement in 1984. He briefly came out of retirement to conduct the Purdue University symphonic band from 1985-87.

For many years he was on the faculty of Blue Lake Fine Arts Camp, a director of the Midwest Clinic, and an active conductor and clinician. He was a Contributing Editor of The Instrumentalist for many years and his articles frequently reflected his enduring love of the sound of a full concert band. He could vehemently voice his ideas without giving offense to the other side, a rare ability and a reflection of a warm person, one we will miss.

The following are excerpts from some of his articles that appeared in The Instrumentalist. Click on the link at the end of each excerpt to read the full articles.

December 2002

Nothing Can Match The Wonderful Sound Of a Full Concert Band

By Harry Begian

In the late 1930s, I attended a concert by the University of Michigan Band conducted by William Revelli and came away taken by the sound of this large ensemble. I believed that this was what a band could and should sound like. Here was a beautiful, sonorous, and well-balanced sound coming from a large group of woodwinds, brasses, and percussion – a sound that was pleasing to the ear. It was refined and capable of subtleties and expressivity I had thought possible only from an orchestra. The personnel list in the printed program was roughly as large as for a full symphony orchestra.

The ratio of woodwinds to brass and percussion was roughly in the same proportion as strings to the winds and percussion in a symphony orchestra, approximately 60/40. The sound of the Michigan Band was naturally denser or heavier than the orchestral sound and depended at its core on a large clarinet section consisting of a full choir from sopranino (Eb) to the Eb contralto. This 60/40 woodwind/brass ratio and the full choir of clarinets enabled the band to cover the same dynamic range as a symphony orchestra, from a full, brilliant, and inoffensive fortissimo of brasses down to the softest and most delicate dynamics possible by the woodwinds. The most important quality of the sound was the wonderful balance and blend with the textural clarity. This refined, lush sound was so pliable and adaptable that the band could adjust to perform all types of music….

With the advent of the wind ensemble 50 years ago, Frederick Fennell introduced to the band world the musical potentials of small band performances under a fine conductor leading a select group of instrumentalists. The early recordings of the Eastman Wind Ensemble display cohesive performances of very high quality. These performances were technically accurate, rhythmically precise, and had fine intonation. The wind ensemble concept was well received by a younger generation of band conductors, and by the 1970s this form of band became a part of the offerings at many colleges and universities.

The high levels of musical performances attained by many wind ensembles were and are a credit to the calibre of the players and conductors. In my opinion, there are more well trained and knowledgeable band conductors now than ever before. Instrumental playing abilities have advanced so dramatically that the best bands and wind ensembles are able to competently play anything written for bands. With this in mind it is a harsh reality that audiences do not attend wind ensemble concerts in significant numbers. My assessment of why so few people attend current wind concerts and some leave early is that the basic sound and programming of even the finest wind ensembles in this country are unappealing.

To my ears, most smaller bands and wind ensembles have a bright, brass-oriented sound that reminds me most of the army regimental and division bands with 28 to 56 players respectively. These brass-laden timbres are fine for the parade ground but lack the sonority and variety of tone colors for the concert hall. The simple fact is that two flutes, two oboes, and two clarinets do not effectively counterbalance the sound of two trumpets, two horns, and two trombones. Full Text

January 1991

Standards of Excellence For Band Repertoire

By Harry Begian

Student musicians and general concert audiences can distinguish between good and bad music; they also can tell whether that music is played well or poorly. Last May (1990) at the Smoky Mountain Band Festival, the Joliet Township High School Band directed by Theodore Lega performed Elgar’s Enigma Variations. Filled to capacity with student musicians and their parents, the auditorium remained quiet as the audience listened intently. At the completion of Elgar’s work, the audience gave the band and conductor a thunderous and prolonged ovation. It was clear that the audience of students and parents realized they had just heard an exceptionally fine performance of great music by a well-trained band. That high level of playing was brought about by the skilled training and teaching of the conductor. The old cliche came to mind once again: a band is no better than its conductor and is a reflection of what he is and thinks musically….

If music is not worthwhile, then don’t buy or perform it; instead study good band music, such as that listed below or some of the many other fine works that are available for grade levels 3, 4, and 5. The panel I assembled does not claim that these listings are complete, but they feel the pieces are worthy of the time spent in performance and rehearsal. The panel chose works as worthy of being played by school bands. The panel concentrated on grade levels 3 through 5 because groups of this degree of ability can develop the musicality of a work, and directors of grade 6 bands generally know all of the available literature. Full Text

April 1990

The Conductor’s Responsibilities

By Harry Begian

Audience attendance at symphony orchestra, opera, and university band performances reached an all-time high into the 1960s…. From the 60s until the present, symphony and opera attendance have held their own while attendance at university band concerts has dropped.

Decline in the size of band audiences is a major concern for many band conductors and has been the topic of panel discussions and seminars throughout the country. While many reasons are advanced for the causes, one never hears or reads that perhaps the main reason for the decline is poor programming. Far too many band conductors have forgotten, or consciously dismissed, a proper balance of musical responsibilities to both audiences and players….

In the late 1960s and into the 70s, one began to hear from a small group of university band conductors that they did not care to program traditional music from the band’s limited band repertoire; they would devote their musical energies to the performance and propagation of new music, original band works in the contemporary idiom.

This approach to band programming had a direct influence on the younger generation of band conductors being trained by our universities. When this younger generation entered the conducting profession they adopted the programming philosophies of their mentors. Many of them became so intent on personal expression that they showed little or no responsibility for exposing players and concert audiences to a variety of styles and periods of music.

It is my opinion, shared by a great number of band conductors, that programming of a preponderance of one kind of music is shortsighted and cheats our players. Through lopsided programming that stresses only new, original, or contemporary band works, an aura of musical monotony is created, seriously affecting the performers’ enthusiasm and curtailing audience attendance at concerts….

To conductors who regard all transcriptions as anathemas, I say that transcriptions have been considered a legitimate practice throughout the history of Western music. Bach, Mozart, and Liszt are but a few of the great composers who transcribed music of their own as well as that of other composers. Unfortunately, there are far too many bad transcriptions for band: transcriptions unsuited to band performance or executed so poorly they discredit the original composition. Unacceptable transcriptions are those in which the transcriber has freely changed harmonies, textures, and rhythmic figures or made deletions.

However, having listed these objectionable transcription practices I would also venture to say that many bands today perform in concert as many bad original works as bad transcriptions….

When teaching graduate music students, [I find it] distressing to observe how little they know about music literature and music history. This leads me to believe that very few band students ever play or hear music of the masters in their high school or college bands. It may also indicate that many of them do not attend symphony orchestra concerts and operas. In pondering this matter I have come to the conclusion that their playing experiences are confined to the new educational music published for bands and a type of “non-music music” (it looks like music, reads like music, but sounds terrible). Full Text

On Conducting

April 1993

Conducting with Eloquence

An Interview with Harry Begian

By Barbara Favorito

Don’t give speeches. In those first minutes try to exhibit a clean stick and give clear cues. After the first few cues, the musicians’ eyes will emerge from the music. With any ensemble don’t drop the stick before you have their complete attention. If the players are still talking and fiddling, just wait. Give them the eye and a little smile, and they’ll get the message after a while. Be in command from that first moment.

Don’t ever doubt yourself; take charge without being ostentatious. Show that you are prepared and look the musicians in the eye when you cue. Don’t stop unless things get out of hand and remember that good players don’t like lectures. If they’re pros or players in a community orchestra, they’ve probably played under twenty different conductors. Now the twenty-first tells them to play differently. If they don’t catch the idea from the stick, you may have to stop and explain it. I don’t agree with advocates of conducting without any words; listen to the Toscanini tapes. Some people think that conducting isn’t teaching, but that is precisely what conducting is. Speaking is appropriate when you can’t represent an idea through facial expression, gestures, or the baton.

After identifying why you stopped, give a clear solution to the problem. Most conductors neglect to give the cure. Adding “please” at the end of the request works well.

Which of the differences between bands and orchestras are the most striking?

Less experienced conductors who alternate between the two kinds of ensembles may find the differences striking. When conducting wind players, I discuss two attacks: soft and hard. I describe a D versus a T sound. String players can draw the bow to get a sharper edge on the attack or just glide into the note. Wind players can’t glide the way a string player can; they have to give an attack but can modify it by using a D tonguing instead of a T. That sounds simplistic, but it makes a big difference as far as activating the sound.

Another difference in articulation is that bands are far more precise than orchestras; the nature of string response encourages imprecision. If twenty strings attack inaccurately, it is not terribly obvious; with twenty clarinets, it is glaringly obvious to the most inexperienced listener. Intonation also poses a bigger problem for bands. Intonation problems in the orchestra are largely covered up by vibrato. In a band, poor intonation cannot be hidden. Full Text

April 1997

Rehearsals Improve with Effort And Planning

By Harry Begian

Although many conductors use chorales as part of the warm-up, most fail to take advantage of the full musical potential of these works. By approaching warm-up chorales as demanding concert pieces, a director can sharpen the response to his conducting gestures and set an attentive mood for the rehearsal. Through visual contact and clear gestures during the chorale, a conductor can clean up the attacks, correct balance, indicate dynamic or tempo changes, add a tenuto, or improve releases.

After the warm-up I often like to sight-read a short piece with enough technical demands to be a challenge. Marches are well-suited for this purpose because they are technically and rhythmically challenging and span a wide dynamic range. The contrasting styles, tempos, and technical demands of a chorale and march during the warm-up are an excellent beginning for any rehearsal. The remainder of a rehearsal should proceed from the easiest to the most difficult pieces.

Rehearse selected passages that need attention, but don’t feel obligated to play the entire work. It is always best to end a rehearsal with a piece the band likes and plays well so players leave feeling good about how the ensemble sounds, even if it was a difficult session.

Try to make rehearsals fast-paced, serious, and focused entirely on making music. Corrections to the music should be made on the spot instead of leaving these for a player or section to correct later. After diagnosing a problem and offering a solution, students should play the passage again. If a problem persists after several attempts, leave it for a subsequent rehearsal. Conductors who spend an inordinate amount of time on one rhythmic, intonation, or technical problem simply waste time and raise the stress and tension levels often without correcting the passage. Any problem that continues for several rehearsals should be dealt with in sectionals or private sessions. Full Text

August 2004

Conducting Wisdom

From Harry Begian

By Barry Ellis

I learned a great deal by observing professional conductors, who worked in an entirely different manner from what I saw in school. Instead of talking to the orchestra, these conductors came in and all they said was “good morning gentlemen, the Beethoven please” – and wham, the stick came down. The conductor never stopped unless he had to. Only if there was something he couldn’t convey with gestures or by talking over the music as they played would he stop. Whenever this was necessary, the conductor always explained why he stopped and gave specific instructions about how he thought the passage should be played.

This efficiency of professional conductors in using rehearsal time im-pressed me the most. As I watched several conductors over the years, I was also impressed that no two of them conducted in the same manner. Each stood before the orchestra differently, used distinctive beat patterns, and no two of them used the left hand in the same way. I had read in books about the taboos of conducting, including that the left hand should never be used except to cue someone, but these symphony conductors used the left hand all the time, and they used it gracefully.

I also began to notice that no two of them conducted the same piece of music at the same tempo or with the same inflections. I heard Fritz Reiner and José Iturbi conduct Roman Carnival Overture a few months apart and they took entirely different tempos on the same work. This convinced me that professional conductors don’t copy one another but conduct each piece as they see it in the score. The result is that the music reflects the conductor’s perception of the score, which I guess is what some people refer to as recreating the music from the score. Full Text

December 1997

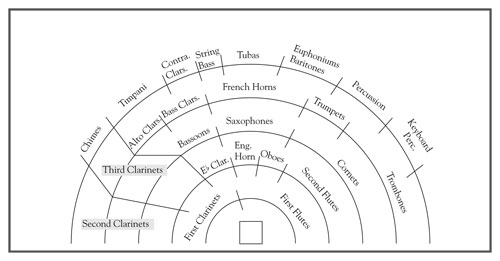

Experiments in Band Seating

By Harry Begian

I experimented with instrumentation and seating plans at Detroit’s Cass Technical High School to produce good balance, blend, and intonation. For good balance the woodwind section should be the dominant sound of the band, with the clarinets as the lead instruments, similar to violins in an orchestra. To add to the resonance and sonority of the clarinet section, I included alto, bass, and contralto clarinets along with the Eb sopranino. Although the alto clarinets were later omitted, I have continued to use the Eb sopranino because it carries the clarinet sound into the upper ranges without relying completely on the flutes.

I also learned that multiple bass clarinets and contralto clarinets help to create a full-bodied and rich sounding woodwind section. The saxophonists in my Cass Tech band were excellent students taught by Larry Teal, so I used only four players with soprano or bass added when necessary. Because the saxophones blend well I seated them in the center of the band between the woodwinds and the brass.

For better balance and a predominantly woodwind sound I toned down the brass section and tried to draw a distinction between cornets and trumpets. This proved impossible simply because all of the players owned trumpets and could not afford both a trumpet and a cornet. The rest of the brass included a full complement of horns, trombones, baritones (euphoniums), and tubas. I consistently used a percussion section of six except on a few pieces that called for more players.

Early in these experiments I learned how greatly a seating plan affects the sound and balance of an ensemble. This first became clear to me at concerts of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra when guest conductors changed the seating of the orchestra. The sound, balance, and blend was different with each seating change and with each conductor’s concept of sound. I later read a music review on the exchange conductorship between Fritz Reiner and Eugene Ormandy that explained how Reiner made the Philadelphia Symphony Orchestra sound like the Chicago Symphony Orchestra while Ormandy made the Chicago orchestra sound like the Philadelphia orchestra.

After considerable experimentation I settled upon the following instrumentation for a symphonic band: 1 piccolo, 8 flutes, 3 oboes (1 English horn), 3 bassoons (1 contrabassoon), 1 Eb clarinet, 16-20 Bb clarinets, 4 bass clarinets, 2 contralto clarinets, 4 saxophones, 7 cornets, 3 trumpets, 6-8 horns, 6 trombones, 4 euphoniums, 4 tubas, and 6 percussion. I have rarely felt it necessary to deviate from this instrumentation of roughly 80 to 85 players. Full Text

Additional Articles

Conducting Marches with Flair and Accuracy, By Harry Begian, September 1994 Full Text

Harry Begian Speaks From Experience, By James Hile, June 1990 Full Text