The warmup may be the most difficult part of a concert band rehearsal to conceive, but it is also potentially the best opportunity for learning. Most of us grew up in the world of major and (rarely) minor scales as a warmup. This was fine as far as it went. Development of tone is, of course, essential, but the warmup can be transformed into a skills development exercise that includes minor scales in all forms and training that would allow students to play many pieces by ear.

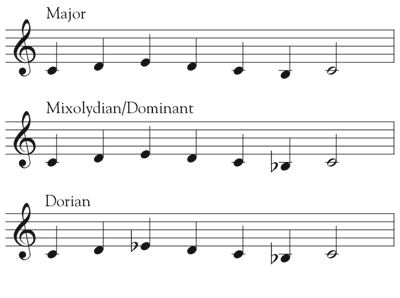

The way to start is to use the scales your students already know as a springboard. If students are fluent in the keys of Bb, Eb, Ab, C, G, and D, each of these can be used to construct new scales. Play a Bb major scale. Have them lower the seventh to create mixolydian (dominant) mode. Then, lower the third to make dorian mode. Explain that dorian is the only minor scale with a regular sixth. Lower the sixth to make it natural minor. Then, raise the seventh to create harmonic minor.

All of this is easy to do, with the added benefit of expanding students’ tonal language. The disconnect between concert band and jazz tonal vocabulary has long been troubling. Good players go from concert band to jazz with little applicable vocabulary. The music literacy of every band member can be increased this way. I reinforce this by having students play seventh chords as a full ensemble after we change the scale. Basses play the root and everyone else chooses a number from one through four, corresponding to root, third, fifth, and seventh (with the basses on the root). Then they play the seventh chords as a full ensemble. It is a great thing to reach the penultimate chord in a piece and be able to say: “Hear the dominant seventh chord, which in many cases resolves to one.” In the future, students will play those resolutions with greater understanding. You can easily expand it to ii-V-I, lingua franca for jazz musicians. You can also teach arpeggios from this material. At one point we were playing the Charles Carter’s Overture for Band and reached a dorian section. Faces lit up when students realized that the sound they were playing was the sound we introduced in warmup. There was context and greater understanding.

We also introduced major and minor pentatonics and whole tone scales. I have tried going to these scales from the major scale, but it works best simply to introduce these scales separately. We start on Bb, and I have someone play up a whole step, and we just walk through the whole tone scale that way. Later, we can show students how these scales differ from major. For contemporary pieces you could also introduce clusters, so that when you reach extended harmonics, students have ears for that type of dissonance and can appreciate it rather than be fearful of it.

Scales by Number

John Cooper’s Linear Transitions is written primarily as a jazz book but is also a wonderful tool for improving concert band warmups. Cooper uses a number system to teach patterns as well as the Circle of Fifths. One option is to have students play 1-2-1 in Bb, then Eb, then Ab, and work through the circle that way. We haven’t made it all the way around yet, but we’re getting there. After that, the next step is 1-2-3-2-1 around the circle, then 1-2-3-4-3-2-1, and so on. This is a great way to learn all the scales without being hung up about what’s on the written page.

Modes can be added to these patterns when running through circle of fifths. The ideal pattern to use is 1-2-3-2-1-7-1. In the key of C this would be C-D-E-D-C-B-C. Change the B to Bb and for a mixolydian/dominant pattern, then lower the third and it becomes a dorian pattern.

It is also possible to go the other direction through the circle of fifths by playing a straight major pattern and then raising the fourth scale degree to create lydian mode. Lydian opens up the world of altered dominants, and the tritone gives students ears for the flattened fifth, which is the characteristic interval in diminished chords and bebop language.

The number concept of learning patterns is also great for teaching scales. I will walk into the rehearsal, pick up my trumpet and say, “Find my note.” When everyone has found my note, I play 1-2-1 up the major scale and have them repeat it. When everyone has done that, we try 1-2-3-2-1, 1-2-3-4-3-2-1, and all the way up through the scale. The first time I tried this, I chose to play Db, and students learned the entire scale painlessly. The patterns create muscle memory, keeping students’ focus on the scale sound, not the fingering or reading.

I catch the occasional self-conscious freshman brass player cheating by watching my fingerings instead of trying to figure it out by ear; I have to tell them not to watch me. An exercise like this gives students freedom to fail, which is something they are unaccustomed to. I give hints to students who might only be a half-step away and frequently remind them not to worry because there won’t be a test. Once students get the hang of it, they pick everything up quickly.

Tunes by Number

Using numbers to teach tunes can also create greater musical literacy. Learning tunes by ear is great fun for the band members and also recalls an almost lost aural tradition. Start with the known, with pieces such as “Twinkle, Twinkle,” “Happy Birthday,” “Old MacDonald,” and “When the Saints Go Marchin’ In.” Just as with the scales, I start these by having students find my note and imitate me. I give students a short melodic phrase, which they play back.

In the early stages, this is easy because the first tunes have only a limited amount of notes. Once melodies start to get a bit more complex, it helps to include the numbers on the board. Some students are great at picking things up strictly by ear, and others need the mathematical aspect of it, while still others use a combination of the two. No matter which students use, we still always start with having them find my note.

The next place to go is blues heads, which have dominant patterns. These tunes are short and generally compressed in tessitura. The perfect place to start is Sonny Rollins’s “Sonnymoon for Two,” which is a four measure pattern played three times.

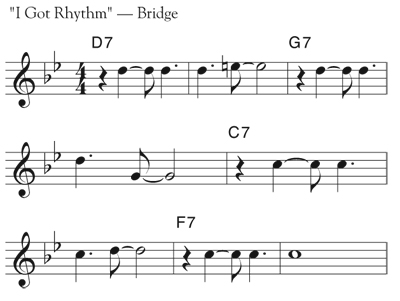

Other easy tunes to learn by ear are “Blues by Five,” “Blues in the Closet,” “Shepherd’s Hey,” Grainger’s “Spoon River,” “All of Me,” “I Got Rhythm,” “Satin Doll,” “Ol’ Man River,” “Bye, Bye Blackbird,” “There Will Never Be Another You,” “Freddy Freeloader,” “Goldfinger,” “Summertime,” “St. Thomas,” “Satin Doll,” and “Blue Room.” The last of these can be difficult because of the expanding arc of the melodic line but is perfect for using the number system. Another piece we learned with the numbers/ear combination was “I Got Rhythm.” We started with the tune strictly by ear because it starts simple and diatonic. The bridge gets trickier because of the raised fourth, so that’s when I went to numbers.

With a freshman/sophomore group, teaching this entire tune took less than 10 minutes and did wonders for interval awareness. There is a new vitality and sense of accomplishment when the group learns expanded scale vocabulary and another piece by ear. One of my great recent moments in teaching came at a jazz festival when a clinician asked one of my musicians what mode the piece was in. “Dorian,” she responded, and I smiled, because that was language she learned in concert band.