Richard Meyer has taught band and orchestra at all levels and currently directs elementary and intermediate orchestras in Temple City, California. Although he is a clarinetist, he prefers teaching strings. “I think teaching strings can be easier than teaching band. String teaching is all out in the open. There are no embouchures, tonguing, or breathing; everything is visual. The tone production is all the same compared to the variety of instruments in the band. Band students can fake it within the ensemble, but it is difficult to hide on a string instrument.” Meyer is also a prolific composer and often writes music for his ensembles. “I started writing in high school. I never took composition lessons; I learned by trying to come up with interesting music for my students. I teach at a music camp in the summer and did some experimenting there as well. Everything I write is kid-tested. It is great to write a piece and hear it played by your students. In college you rarely get to hear anything you write.”

What should wind and percussion players know about teaching strings?

When I was a student teacher, I had a terrific master teacher. Her name was Rosemarie Krovoza. I started watching, then little by little began playing and learning the jargon. I encourage wind players to watch as many string rehearsals as you can to learn what words to use. String players use a certain vocabulary that wind players should know.

The biggest compliment I can get when I run clinics or guest conduct is when they think I am a string player and are surprised that I play clarinet. The drawback of being a clarinetist is that I cannot always grab an instrument and demonstrate something at a higher level. My students in the Oak Avenue advanced orchestra have passed me and they know it, so I use them to demonstrate. In other situations I have to explain things in a way that students can understand. That can be a challenge, but it should never stop someone from being a good string teacher.

How do you teach beginners when you only see them 45 minutes per week?

It is quite difficult. Beginners are separated into violin, viola, and cello classes (we don’t start basses in elementary school), which range from 12 to 50 students, depending on the instrument and the school. Although fourth grade is the beginning year, students can begin in any grade after that. I start beginners with a rote-playing system based on a modified Suzuki method. There is no note-reading the first semester; I have a curriculum of four different songs that students are required to memorize. Once we learn how to hold the instrument, bowing, and a D scale, we start with the songs, which are “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star,” “French Folk Song,” “Are You Sleeping,” and “Song of the Wind.” This first-semester curriculum is also the beginners’ music for the spring concert. Every student is expected to come up in front of the class and play each song from memory when ready. I bring students up in groups of three or four and accompany them while watching for memory as well as reasonably good position and intonation. If students can play the song, they get an A. If not, or if the wrist or bow hold is poor, they have to try again the next week. Students can move at their own pace, so one student might still be on the first song while another is on the third.

Second semester for the beginners is devoted to note reading and preparing to play in the advanced orchestra. The focus is for students to make sure they can stay with the class. The assignments are short and reasonable to learn and include thirds, arpeggios, the D-major scale, and a few songs that include slurs and hooks. Students are also expected to play half, quarter, and eighth notes in all combinations and to read music by the end of the year. If they can do that, I give them a golden ticket, similar to Willy Wonka, at the end of the year. This ticket allows them to play in the advanced orchestra next year.

The advanced group meets twice a week for one hour with most rehearsals starting before school and dovetailing into the school day. We read out of the method book and play some Suzuki warmups. I test students periodically; they play in front of the group so I can give pointers on how to improve. This group also plays a lot of repertoire, although we do not perform all of it on concerts. Because all students can read music at the beginning of the year, we simply move through the method book and finish it by the end of the year. In sixth grade the curriculum is the same; the difference is that fifth graders sit toward the back of the section or play second violin, and sixth graders play first violin or become section leaders and are expected to set a good example for the younger students.

How do you start basses and balance instrumentation?

At the end of their sixth grade year, we share with students the harsh reality that there are always too many violin players at the intermediate school, and it will be difficult to get on a first part or make the advanced group, even as an 8th grader. Many of them listen and switch to viola, cello, or bass during a 19-day summer program. Students who want to switch instruments join with those who were beginners the past year and want to be sure they can play well enough to move into the 5th-6th orchestra. Local high school students are required to complete 100 hours of community service to graduate, so they often earn some hours as coaches helping with this group.

There is also an advanced summer orchestra, which is made up of the Oak Avenue seventh graders and the elementary advanced orchestra students. This is a reading orchestra and sightreads every day. They also play music theory games and students have the opportunity to conduct. I try to keep it fun, but the goal is to work on sightreading skills. No concerts, we just read. Going through repertoire is important.

How do you catch students who are poor readers?

No student at Oak Avenue is a non-reader. If they somehow get into a group that is more advanced than they can handle, they go back down a level. The intermediate and beginning orchestras meet at the same time, and I have had students go across the hall halfway through the year because they fall behind on their reading.

It can be difficult to figure out who can read music and who is playing by ear. I have to listen to every student, and I use tricks to check them. When testing students on a line in the method book, I never start at the beginning of the line. I might have them start in the middle of a phrase or just ask for the last three measures of a piece. This is a great trick because anyone who has the whole line memorized will falter if asked to start halfway through. Students who ask if they can start at the beginning give themselves away.

How do you divide the Oak Avenue orchestras?

How do you divide the Oak Avenue orchestras?

All of the classes at Oak Avenue are grouped by skill rather than grade. There are three orchestras: beginning, intermediate, and advanced. I audition all the sixth graders at the end of the year using a page of thirds and arpeggios that includes shifting and four key signatures. Most students join the intermediate orchestra as seventh graders. A few make it into the advanced orchestra; this year that group has 75 students, and 12 of those are seventh graders. Approximately 25% of the students in the top orchestra study privately; there is a good base of private teachers in Los Angeles. A number of our students also play in the Pasadena Youth Symphony, which I conducted for 16 years and is currently led by Jack Taylor, the band director at Oak Avenue. Jack also directs the school’s intermediate orchestra.

Not every eighth grader makes it into the advanced group. Parents sometimes ask why their child was not selected for the advanced group, but a student who is not ready will struggle. I ask whether the parents want their child to get a D in advanced orchestra or be a leader and earn an A in the intermediate group. Parents usually appreciate such honesty.

From your perspective as both a teacher and composer, what makes music good?

A good piece should interest both students and teachers. I look at all the parts before I pick music and think, “Would I want to play this part?” I wrote an arrangement for full orchestra once, and as parts were printing I noticed that I had written almost nothing for third trombone; the part had only three notes with a bunch of rests. I realized I had to give this player more to do. Each part ought to be interesting and have some sort of melodic sense to it, even if it is an accompaniment part. It should move in a logical way rather than simply filling in all the extra notes, like one of the inside parts in a barbershop quartet. If you copy that idea over to string writing and just stick all the extra notes in the viola part, the music will sound terrible. A sense of melody, even for the accompaniment parts as they fill in chord tones, is important to me.

When I write a new piece I make sure that everybody gets the melody at some point. I also reorchestrate themes when they reappear. As a string editor I see compositions in which a composer has essentially cut and pasted sections; a theme is orchestrated exactly the same way each time it appears. I prefer to change things or throw in something unexpected to make certain students are thinking and reading. Students love anything in minor or modal. I also try to write a lot for very low grade 1, especially music in 3/4 – there just isn’t enough.

Grade 1 is the most difficult level for which to write interesting music. Anyone can write something easy, but to write something for that level that both students and teachers will remain interested in is difficult. Dr. Seuss once bet his publisher he could write a book with no more than 50 different words. He not only won the bet, the book he wrote with this restriction was one of his best, Green Eggs and Ham. Composers for young players obviously have a limited number of notes and rhythms at their disposal, but they still should make their work interesting and educational.

What do you recommend to aspiring composers?

I encourage beginning composers to write music using a theme and variations form. Pick a strong folk theme and write variations on that; this is a good way to flex your composing muscles. I love this form because it keeps you on a certain path harmonically and melodically but also requires creativity. This is a good way to learn what sounds good on various instruments and what doesn’t work.

Fast and minor is fun, but students should also learn how to play music that is slow or legato. This is another reason I like theme and variations; you can always have a slow variation. Composers can also vary time signatures. For young players, write a legato variation, a 3/4 variation, one where the fingers are flying, one in modal, and you have a finished piece.

What factors are most often overlooked when composing?

The range of the instruments is important. When I start writing, I find a theme and come up with the harmony first, This can be difficult because there is no great key for a middle school symphony orchestra. A major causes trouble for the trumpets and clarinets, and flat keys may cause the string players to struggle. Often we have to meet in the middle at C major. F major is not the best key for strings, but they should learn that key in middle school. F major, G major, and C major are the best choices, with D major being a possibility depending on how busy the woodwind parts are. I have occasionally found what I thought was the perfect key only to discover that it put the trumpet part out of range by three notes.

What one bit of advice would you give to new teachers?

Remember that you are teaching people, not music. The students in the back of the group for whom it doesn’t come easily or quickly are the core of the program, so make sure to give them enough attention and help. That took me a while to learn. I think young teachers want to prove what they can do by going to festivals, contests, and parades. I’ve taught for 32 years now and am getting towards the end of my career. I have made the Giving Bach program I started a priority for my students and the community. I’ve already done all the other stuff.

What is the Giving Bach program and how did it start?

I started the Giving Bach program as a way to help build character in my students. I have seen it improve leadership skills, encourage empathy, and increase confidence. The program consists of concerts at which we demonstrate all the instruments, play pieces in which the audience can participate, and possibly bring an alumni soloist.

The idea came from hearing a Yo-Yo Ma quote comparing performers to waiters; in both cases their job is to deliver an enjoyable product and make sure the customers are happy. Suspecting that my students had never considered their audience before, I asked them what was the number one reason they made music. Out of 76 students, only 6 mentioned the audience. The other 70 talked about themselves, as was expected, because that is every middle school student’s favorite subject. Common comments included, “It makes me feel good,” “Music lets me express my emotions,” or “I think music will help me get into a college.”

I came back the next day with the results and two signs I had made. Both had the word music, but on one the i was highlighted in red, and on the other us was in red. I asked students what they thought the signs meant, and they all understood that the i referred to a self-centered approach to playing. For the us, students initially thought it referred to all of the ensemble members playing together. From that I led them to the idea that it was performers and audience.

After that conversation, I thought of the name Giving Bach and called a local therapeutic school, Five Acres, for foster children and students with learning disabilities such as Asperger’s or mild autism. They jumped at the offer of a performance although the principal was a bit wary about us interacting with her students at first.

How are the concerts set up?

The concerts have two phases. The first part is to provide a great concert. Often the people in the audience have never been to a classical concert, so I go over how to behave, including when to clap. I explain that listening to a concert is something you do alone, similar to reading silently.

We tune in front of them and show how and why students tune. Then we play a piece; I like to play a Bach piece because of the name of the program. Another good choice is an upbeat work such as Light Cavalry Overture, something that students can play confidently and the audience can get excited about. We might even do two pieces depending on the age of the audience and how much time is available.

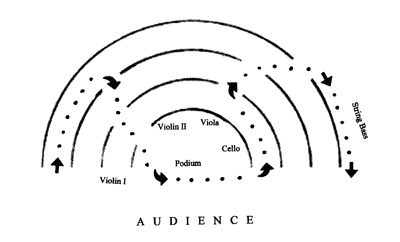

Next, we demonstrate each instrument. The violins stand and play a section feature, followed by the other instruments. I have written short pieces that highlight each section. Then we play another full-ensemble piece, something interesting or unusual. I sometimes program a percussion piece in this slot and invite a few students from the audience to come up and play maraca, claves, or woodblock while my students guide them. The next step is an audience walkthrough, where we have the audience walk through to hear and see the orchestra up close while we play.

I experimented with this in my classroom, putting tape down so I know which way the audience will walk and so my students know how to spread out for this number to leave room along the path.

An orchestra member leads the group through. I have often thought that adults and parents would enjoy the walkthrough as well, just to hear how it sounds in the orchestra. I give walking students two rules: don’t touch any instrument and try to keep moving.

Side-by-side instruction comes next and is often the most powerful element of the concert. Sitting and listening to a concert is educational, but there is nothing like participation. To begin this, every other orchestra member goes into the audience while every other audience member takes the now-open seats in the orchestra.

My students show their partner the parts of the instrument and how to hold it, followed by plucking the strings. Orchestra students show which string is the D string. I wrote a very short piece called “D String Blues.” A small core of our students play the orchestra parts while everyone else claps the audience part. Then orchestra students demonstrate how to play it by plucking the D string.

.jpg)

I remind my students to lean toward their partners and get their eyes engaged. Then they pass the instrument over and play “D String Blues” again plucking. Then we show how to play it with the bow. We play “D String Blues” two more times, once with my students bowing and once with their students bowing. At the end we give students who try instruments a certificate, which always causes excitement. After the first concert, we heard many proclaim they were going to get it framed. One of my students demonstrated her instrument to a school administrator there, and he has his certificate hanging in his office next to his master’s degree.

We play the final piece without changing places. My students either have it memorized (because half of them will be playing from the bleachers) or their partner holds the music for them. We play something quiet to bring the excitement in the room back down to a manageable level.

How did you prepare your students for this?

Before the first performance, the principal from Five Acres came and talked to my orchestra about the students at Five Acres and what they could expect to see. I also had my school’s counselor come in and talk about it, and we found a video from 60 Minutes about a student at Five Acres. We gave four concerts at the school that year. The third concert was when we first brought the Five Acres students into the orchestra to try instruments. Watching the students from the two schools mingle and learn from each other is probably one of the most powerful experiences of my career.

For more information on the Giving Bach program, visit www.givingbach.org.

Richard Meyer is in his 32nd year of teaching and currently teaches orchestra at Oak Avenue Intermediate School and the elementary schools that feed into it in Temple City, California. He was the music director of the Pasadena Youth Symphony Orchestra for 16 years, conducting them in performances in New York, Washington D.C., Vienna, Australia, and Canada.

He is also a prolific composer with 130 pieces in print and one of the string editors for Alfred Publishing. His composition Millennium won the 1998 National School Orchestra Association composition contest, and his Geometric Dances were awarded first prize in the 1995 Texas Orchestra Directors Association composition contest.