Part of Chicago’s Noble Network of Charter Schools, Pritzker College Prep was founded in 2006 with only ninth graders. Benjamin Das started the band program in 2007 with just freshmen and sophomores, none of whom had played an instrument before. “I came in with three years of experience, having started a middle school band program in Boston. As most first-year teachers are, I was too soft and buddy-buddy. I was worried about students’ emotions too much and would get offended if they weren’t listening to me. At the suggestion of my principal at the time, I spent a day observing an orchestra teacher in New York. His discipline was great. The students all sat on the edge of the chair and were holding their instruments and bows in a certain way when they weren’t playing, and I wanted that. I was especially struck that although it was disciplined, the environment was positive and encouraging, not dark or oppressive. I had never seen that before, especially in an urban school. When I came to Pritzker, I focused on teaching students to be disciplined from the start. A new teacher can’t wait half the year to start demanding perfect posture; it has to be that way from day one.” The program has flourished, and a number of students come to Pritzker specifically to join band. Das and his students presented a clinic on the practical application of Japanese band methods in urban schools at the 2016 Midwest.

How do your students begin instrumental instruction?

Before anything else, we learn how to enter the room and sit with perfect posture. That takes a class. Students are responsible for setting up the room, and I am particular about the rows being perfect. If everyone in a section is facing the same direction and sitting with perfect posture and feet the same, it makes it easy to see who is using an incorrect fingering.

Next is a guided meditation, which lasts 10-20 minutes. If students are too antsy then I’ll make it go longer. I don’t call it a guided meditation; the point is to have students realize their potential for focusing for long periods of time. I have them close their eyes and sit on the edge of their chairs, palms down on their lap. I have them notice their toes, wiggle their toes, then take attention away from the toes and come up to their hands. I have them hold their hand out and wiggle their fingers. The aim is to get them to know their bodies without looking at them.

Then, we focus on sounds in the room. If someone walks through the hall, I point the sound out and then tell students to turn that sound off and put their attention elsewhere. I bring their attention to the air and the space around them, then give them a talk about how this is our canvas. Every sound we make is a mark on the canvas, either good or bad. I want students to have the mindset that the air is where we put vibrations to come together to create music.

I used to have long, drawn-out instrument demos complete with YouTube videos. Now I take roughly one minute per instrument. I let students try some instruments; if one doesn’t click right away, then I get them excited about something else.

I assign instruments. Before we ever start, I say, “The class is not called trumpet, or flute, or clarinet. You are picking band, and it comes down to what works for you, what the band needs, and what is available.” Students give me their top three choices, and most get their first. Students also learn from the beginning whether their instrument is a soprano, alto, tenor, or bass instrument, which is important for many of the exercises we do.

What do you play first?

I am against teaching quarter notes too early. I like to take my time on long tones until students produce a consistent sound. Every time we learn a new note, we turn on a drone and go around the room in many different ways.

One exercise we do when learning a new note is to start with the bass voices and focus on a good bass sound. I start with the student who has the strongest sound, whether this is a tubist, bass clarinetist, or bari sax player. That students starts, and all other bass voices play to fit into that sound.

When the bass sounds good, we add the tenors. I describe it as painting on another layer. We’re adding to it, not covering it up. We do talk about the pyramid of sound, but I don’t harp on it. The visualization is good, but I have heard a lot of directors say, “The pyramid! The pyramid!” and little more. Instead, I stop the group, and we start layering the sound from bass on up again to experience the pyramid. Because we do this in unison right from the beginning, as we start repertoire, I can stop on a chord and say, “Measure 42, beat three, bass,” and then tenor, alto, and soprano instruments are prepared to come in when cued.

I was out on paternity leave earlier this school year, although I occasionally came back to the classroom for a few days here and there. One class sounded rough, so we spent 45 minutes on long tones. I mixed things up, using different pitches or instrument groupings and giving them breaks, but students’ cheeks were feeling it by the end. The next day, they sounded great on the exercises they learned without me.

When I do introduce quarters, it is framed as moving the tongue, so that students learn that the air never stops between quarter notes. All tonguing should be legato at first. In the beginning, progress seems slow, but because the tone develops so quickly the way we do things with long tones, we move faster in the end. By the end of the school year, students can handle grade 2 music, because when they are confident about their sound, they hit pitches. I think a lot of students will play a note, and if it sounds bad, they think they are doing something wrong and eventually lose the desire to keep playing. Because we worked hard on the tone in the beginning of the year, we accelerate quickly through the book.

How does a typical band class run?

After the room is set up, I always give students a few minutes to play on their own, which gives me time to take attendance and give out any supplies students might need. I used to have them come in and sit silently in position before we could start playing together, but I think it is important that they find their sound for two to three minutes before we start. I give frequent quizzes on scales and repertoire, so students know to get to work rather than play with cell phones or talk with friends.

After this, I clap my hands to get everyone’s attention, and then either a student or I will start warmups. I don’t like major scales and marching band type drills for warmups. I think those are just physical warmups, which are better suited for student practice time. Warmup time is about developing the ensemble sound. We work on balance, unison playing, or harmony, and this takes up at least half the class. At the beginning of the year we might not touch repertoire for a few weeks. Even before a concert, if the class doesn’t sound good, we work on the sound rather than the repertoire.

How do you develop a good ensemble sound?

Ear training is key, and singing is the fastest, most efficient, and most effective way to develop the ear. In Japan, students learn to sing in primary school, but this is not the case in the United States. To get students comfortable singing, we start with humming long tones. The next step is to start with a hum and open the mouth to an aah sound. This creates resonance and gets students comfortable with projecting the sound. From there we start with unison singing and gradually expand to harmony.

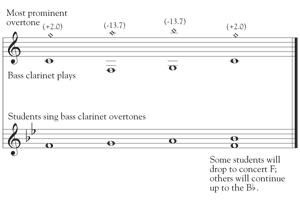

The bass clarinet is a useful instrument for developing the ear. Ask a bass clarinetist to play written C4, and have students listen for the overtone a 12th above and then sing it. When the perfect fifth this creates is in tune, the bass clarinetist should change to F3. The overtone you want students to hear is the high concert G, which is a whole step above the overtone the C4 produced. The bass clarinetist then moves to G3, giving students the leading tone, and then back to C4 on the bass clarinet, which should get students to naturally progress up to the octave, even though it isn’t an overtone on the bass clarinet. The first time I tried it, half the students went up to do, the other half dropped back to sol.

People should pay more attention to overtones; this is where this pure intonation comes from. If the bass instruments weren’t playing with overtones, it wouldn’t matter, because we wouldn’t get the dissonance between their overtone and the pitch of the higher instruments. If we play a concert Eb chord, and the bass clarinet is on that low F, students have a ringing major third overtone to tune to. If students are not trained to adjust their thirds, then it will sound rough, but if you have a drone that can be set to 13.7 cents flat, you can use it to play the third against the bass clarinet’s low F. Have the bass clarinetist start, add the drone, and then fade the drone back out. Everyone should still hear that overtone ringing.

How do you teach balance and blend?

Balance is the chord, blend is the instrument’s voice. Students should know their voice and which part of the chord they have. In a Bb major chord, a trombonist playing D4 should know with which instruments the sound should blend – possibly a tenor saxophone, horn, or alto clarinet – and that the D should be a little flat.

Numerous modern band pieces have ninths and thirteenths, but one, three, and five are more than enough to keep students’ ears busy and working all the time. I don’t think any director has a band full of students who know that they’re playing the 13th, but everyone should promote awareness of the root, third, and fifth.

I help students hear harmony by having them play the first note – no matter how short or long it might be – of each measure of a passage as a whole note. The chord might change a few times per measure, but that is not what this is about; the point is to help students hear the direction of the harmony from measure to measure, so they play more in tune going forward. We often do this as part of our harmony training in the first half of class, especially if a passage is particularly tricky.

This technique also works well with marches, especially the fast ones. It is difficult to think about tuning when the fingers are flying to cover all the notes. This can show students that we might be on a I chord for four measures before moving to a V chord. Now they know they have four measures to build toward a target: the chord change.

The flutes might have F, F, G, G, F# as the first notes of five measures. This is easy enough to memorize after just a few seconds of study, meaning now they can focus on keeping those notes in tune and listening to the rest of the group. They should be able to figure out what part of a chord each note is and adjust accordingly.

Do not move on if an exercise doesn’t sound good. Make sure that a chord is in tune before moving on, for better or worse. It might make the repertoire less tight rhythmically in the concert, but I would rather students have a lasting sense of good intonation and take that to college. Their college director will get them to play as an ensemble with their new ensemble. I’d want them to be prepared for that.

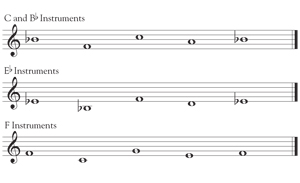

How did you develop your five-note tuning ritual?

Our jazz band saxophones got really good at tuning to concert A. It didn’t matter where their mouthpiece was; they could always find A because their ears and embouchure flexibility were both good. They would always find A, but then they were out of tune once they went to play. It proves that you should never tune to one note. The trouble with tuning only to one of Bb, A, or F, is that students only get good at playing Bb, A, or F. That isn’t the same as being in tune. It is better to find the average of a few notes, so my students learn a sequence of tuning notes. Once a musician’s ears are good enough, they can bend notes to fix pitch quickly.

I have graded tuning before, meaning I made it a grade in the grade book that you have to match these pitches quickly by ear – no visual tuners were permitted. It sounds crazy, but everyone was able to do it after two weeks. I teach students to play their tuning sequence on the piano, so one would sit at a keyboard and play the notes, and the others would tune themselves and each other. Now they tune each other in rehearsal, in sectionals, and everywhere else. I don’t have a tuning ritual; it is considered individual work, and a student might raise a hand in rehearsal to ask to go to a keyboard and tune.

Before students played at the Midwest Clinic as part of my presentation, the flutes were having a rough time tuning, so I sent them to the corner to go figure it out together. They all huddled up in the corner and went through the notes together, checking against the lead. I think it is good to make students obsessed about tuning. You get them to believe in it, and then they practice it.

What are other ways you motivate students to practice?

I run a voluntary summer program for four to five weeks with help from alumni and older students. At the end of freshman year, I introduce all 12 major scales. Their summer assignment between freshman and sophomore year is playing all 12 major scales in one octave. They are allowed to read music when they play the scales, but the assignment still scares them. My offer is that anyone who comes in for at least 25 hours over the summer is exempt from those quizzes when school starts – and they get 0.25 enrichment credit. There is a double incentive for students. Some students don’t need to get out; they would ace their playing quizzes anyway. Others do not need the enrichment credit. These students still come in. This past year, it was 70-75% of the students in band put in at least 25 hours over the summer.

The summer program is also open to incoming freshmen. We send home a letter saying that students who attend the summer program receive the enrichment credit and are guaranteed their first choice of instrument. These students get a head start and often turn into my leaders for the freshman band because they played with older students over summer. They feel more confident going into their freshman class and leading, because they made friends with students in the junior and senior classes.

During the school year, students are required to pass off on their concert music or they are not permitted to play the concert. I assign passages in the music, and students have to score 90 or higher to play with the band on the concert. Auditions are two weeks before the concert. Most students make the concert. This is my way of getting everyone to work harder. Some people believe everyone should have the experience of performing, but there are some students that take away from the ensemble. If one student practices an hour a day, and another only touches an instrument in band class and is disruptive to boot, I find it unfair to those who worked hard to let the slacker perform.

Students at Pritzker often practice in groups before or after school. How did this culture develop?

This started partly because I realized students couldn’t practice at home and partly because I didn’t want to lose class time listening to playing quizzes. I made students come in during office hours, and if a student just quizzed with me and got a 95%, I’d say, “Hey, I’ll give you 100% if you go help your section mate in the practice room right now.” Students saw this as easy extra credit, and that evolved into a culture of helping each other. Working in groups also happened naturally because students were in the same room practicing, so the altos would group up and practice the same exercise together, and the trumpets would group up and help each other.

Older students are responsible for teaching the younger students, and they like to do that. They feel pride that they have something to share with younger students. I haven’t taught how to put a clarinet together in eight years because there are students who could teach it better than I can.

When I observe a senior teaching a freshman, rather than talk to the freshman about problems I see and hear, I talk to the senior about them. I’m teaching them how to teach the beginners. I can teach beginners one on one, but the older students are better at their primary instruments than I am and can more easily demonstrate good technique and sound production. Build up the strongest players, and they will spread their expertise to the rest of the group.

Pritzker students tuning at the 2016 Midwest Clinic.