.jpg) Why does the world need bands? Why does the world need flowers, sunlight, religion, the laughter of children, moonrise in the mountains, great masterpieces of art? Why, indeed? Because the world has a soul, a spirit, which is hungry for beauty and inspiration. Years ago we used to be told the smallest conceivable thing was an atom. Now they are actually measuring electrons, which are infinitely smaller than atoms; and I suppose that some day, some time, some where, exophthalmic scientists, with gauges, calipers, and micrometers, will attempt to tell just why bands have such an amazing effect upon mankind. Mankind, from the days of the pyramids, has instinctively demanded groups of instrumental players, and from that day to this there has been a constant progress in the development of the instruments, the players, and the music itself. We are living in the greatest period in the history of mankind, but we are all living so fast that hardly one person in ten seems to realize our glorious advantages, to say nothing of enjoying them. At no time in the history of art has the band, for instance, attained a higher degree of excellence than at this moment. The improvement in the instruments has been nothing short of marvelous, and the players have acquired a degree of proficiency that is so high that anything short of virtuosity prevents a player from joining high class organizations.

Why does the world need bands? Why does the world need flowers, sunlight, religion, the laughter of children, moonrise in the mountains, great masterpieces of art? Why, indeed? Because the world has a soul, a spirit, which is hungry for beauty and inspiration. Years ago we used to be told the smallest conceivable thing was an atom. Now they are actually measuring electrons, which are infinitely smaller than atoms; and I suppose that some day, some time, some where, exophthalmic scientists, with gauges, calipers, and micrometers, will attempt to tell just why bands have such an amazing effect upon mankind. Mankind, from the days of the pyramids, has instinctively demanded groups of instrumental players, and from that day to this there has been a constant progress in the development of the instruments, the players, and the music itself. We are living in the greatest period in the history of mankind, but we are all living so fast that hardly one person in ten seems to realize our glorious advantages, to say nothing of enjoying them. At no time in the history of art has the band, for instance, attained a higher degree of excellence than at this moment. The improvement in the instruments has been nothing short of marvelous, and the players have acquired a degree of proficiency that is so high that anything short of virtuosity prevents a player from joining high class organizations.

The Lure of the Band

The band holds an entirely distinctive place in music. It affords a means of stimulation that cannot be acquired in any other way. This is such a common experience that to comment upon it is scarcely necessary. Oh the thrill that travels up and down the normal spine when a fine band is heard marching down the street!

The smart band of today can boast the most ancient ancestry in music. All in all it is the oldest combination of instruments that we use. Many of the instruments in the band of today are lineal descendents, ancestors of such remote Asiatic origin that historians are at a loss to discover their beginnings. The oboe and the bagpipe are older than Methuselah. The first brass wind instruments of the Egyptians, as their barges floated down the Nile toward the mysteries of Karnak, were apparently straight metal trumpets blown through a cupped mouthpiece. These were much like the straight trumpets which Verdi used so ingeniously in the “Triumphal March” in Aida. Curved brass instruments apparently were not used until Roman times. Therefore when Local No. 46 appears in the Temple in the Second Act of Aida, playing an assortment of modern trumpets and tubas from American instrument factories, they present an anachronism as ludicrous as Shakespeare in plus fours. Yet the players usually wear spectacles and carry modern printed music scores, so we must not be too carping. Still, what would this Second Act be without that inspiring band to put the flavor of brass into that vivid scene? In fact the pomp and circumstance of fate are almost unthinkable without a band.

Bands in the Middle Ages

Instruments of the band began to improve in the Middle Ages. It must be understood that at first bands were an outdoor affair. The blare of the instruments of that time would have been insufferable indoors. However, with the coming of the great inventors and innovators, such as Boehm, Sax, and Wieprecht, the instruments were so vastly changed and improved that the most pianissimo effects were obtainable; and the band is now equally effective indoors and out. More than this the instruments have become infinitely easier to play, and the effects comparable with those of the orchestra are now easily attainable. The Boehm flute, for instance, offered great improvements in facility and intonation, and, because of similar betterments of many of its instruments, the band of today is even cleaner cut than the orchestra. The double bass of the orchestra has much less capacity for execution than the basses and tubas of the band. Only in the case of real virtuosos of the double bass do we have that definition and unity of intonation in an orchestra that we expect in the brass band.

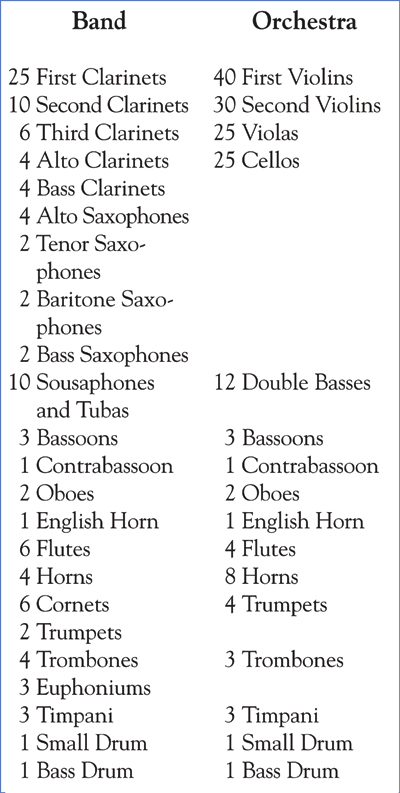

In tonal mass, naturally the band can produce large effects with fewer instruments. Let us make a comparison of the concert band and the symphony orchestra. A band composed of one hundred players would have a far larger volume than an orchestra of 156 instruments. The following outline affords an excellent means of comparison.

The average man of today gives small consideration to the enormous improvement in thousands of things that make life more wonderful than at any previous period in history. This has affected musical instruments quite as much as it has transportation, communication, hygiene, and the thousand-and-one domestic toys which add alike to our joys and our electric bills. Wind instruments have improved so much that Mozart and Beethoven would dance with delight if they could hear one of their compositions played by a modern orchestra or band. In fact it may be safely said that they had but a small conception of how their works would sound as we now hear them daily at concerts or over the radio.

Introduction of the Tuba

It was but a comparatively few years ago that the bass of the band was an ophicleide, which was nothing more than a cumbersome keyed bugle in the bass clef. Wieprecht, head of a musical department in the German army, invented the tuba that is used today. The limitations of the ophicleide account for the fact that many of the European bands have used string basses. In fact the famous Belgian Band that toured America in 1928 employed string basses. The expert tuba player, as I have said, can far excel the average double bass player in intonation, and therefore string basses in a band are wholly unnecessary. They have disappeated in practically all American bands.

When I became conductor of the Marine Band in 1880, practically all of the instruments were of French and English manufacture. At that time comparatively few good instruments were made in America. The foreign instruments, the best at that time, were not capable of really first-class intonation. Now I believe that by far the best wind instruments of the world are made in America. There is not a foreign instrument in my band. A protective tariff plus the great growth of music in America has fostered this industry. Quality, however, is the determining factor, and if superior instruments were manufactured abroad, we would have to pay for them. At present, however, I would be willing to pay a premium for American instruments, as compared with the best I have heard from overseas. The industry would not have arrived at its present position so quickly if it had not been for protection, but quality is, after all, the thing that holds it there. When the matter of increase in tariff came up in Congress years ago, I urged that some of the revenue should go for an increase in the salaries for the marine bands.

It would be a thrilling experience for the average music lover to visit a factory where band instruments are made. Machinery, with the precision of a fine watch, is employed in producing many even frail parts that formerly were obtained only by cumbersome hand tools. Of course there is still a great deal of hand work in finishing delicate processes.

The Quest for Tone Color

The history of instrumentation has been largely that of a quest for tone color. The pigments of the composer’s palette are the voices of the different instruments of the orchestra and the band. The quest for new tone colors is more intense now than ever before. Of course exquisitely beautiful effects can be achieved in musical monochromes, just as art rises to great heights in the blacks, greens, and sepias of the master etchings of the great painters, from Michelangelo to Whistler. Every new instrument introduces a new color. Even in the string quartet the violin has a different tone color from the viola or the cello.

The pipe organ does, it is true, have a great variety of tone colors, and the combination of the pipe organ with the band or the orchestra sometimes produces magnificent effects, but the organ is always an organ. This is due to the overpowering effect of its diapasons and other characteristically organ pipes. The imitation of strings produces an effect that is often very beautiful in itself, but it fools no one.

Tone Color of Instruments

The piano has a distinctive tone color all its own, as well as its literature. The great facility with which music of all kinds may be transcribed for the piano accounts for its eminent position and universal employment. New instruments are often very slow in gaining recognition. The sax-ophone, which (with the exception of the soprano saxophone) is one of the mellowest of all instruments, was invented in 1842 by Antoine Joseph Adolphe Sax. It was instantly and warmly endorsed by Berlioz; but it was not until some 70 years later that it became one of the most popular of all instruments, a rage that started in America.

I am often asked if age affects wind instrument players. This, unfortunately, is the case. The sound in wind instruments is merely the intensification of vibrations of the lips of the player (called embouchure) in the air chambers of the instruments, which are lengthened or shortened by the valves or slides. The lips can stand this strain only just so long. The period varies with individuals. The embouchure must always be fresh. Most brass players are obligated to retire at 60 or 70 except in abnormal cases. Woodwind (especially reed in-srument) players are not affected so much as those of the brass.

To the question, “What instrumentalists command the highest salaries?” there is no final answer. It is purely a matter of supply and demand. Instrumentalists that are hardest to secure are the ones who earn the most money. Just now the instruments that are not used in the orchestra, notably the cornet and the euphonium, are hard to secure. Some players receive as high as $200 a week. My players receive, on an average, far above the union scale.

The problem arises as to the nature of the material of which an instrument is made and its effect upon the sound of the instrument. It has always seemed to me, and I am sure that many physicists will agree, that the only thing that counts is the vibrating column of air. Flutes of wood, silver, brass, ebonite, or glass, made identically, would sound identically. The old silver cornet bands, such as the one in which President Harding played, and which were the joy and delight of the countryside, were not silver cornets at all, but instruments made of brass or alloys and then silver plated. What a smashing appearance they made when the perspiring boys got together on a Saturday night of June and fought their way through the Poet and Peasant Overture or General Grant’s Grand March.

Now the brass instruments are made of brass, often silver and gold plated, and the woodwinds are likely to be made of ebonite. Big bands have become the fashion in modern times, but when they become too large they are inelastic, cumbersome, and inartistic. Patrick Gilmore, years ago is his Peace Festivals, used to resort to mass bands. Recently in Madison Square Garden I led a massed band of 2,000 players.

Wonderful School Bands

The student bands in our public schools are reaching an amazing status. There is far more interest in this activity in the West and Middle West than in the East. The normal boy always finds a joy in playing in a band. He seems to incline far more naturally to the band than to the orchestra. It is about as difficult to coax the average boy to play in a band as it is to coax an Airedale to eat beefsteak. He soon finds that, however delightful it may be to listen to music, it is ten times as much fun to play the music himself. He forgets the routine of practice in his intensified interest. Start a boy in studying music in the right way – get him past that critical point where he has acquired sufficient technique to make playing easy – and you have a boy who will be in music for life. No matter if he rises to the highest office in the land, he will find that his life interests are enormously expanded by music.

To my mind the introduction of student bands in public school work is a godsend to America. Take my word for it, these organizations will galvanize thousands of lackadaisical and undisciplined youngsters in a way which would not be possible in any other manner. Authorities in prisons have found that the introduction of bands has a wonderful influence upon discipline and character. The trouble is that they are brought in too late. The boys that are playing on musical instruments behind bars might never have gotten there if they had learned to play them before they got in. A boy with a cornet or a saxophone, learning to play Massenet’s Elegy or Bizet’s Toreador Song has very little time to lay plans for becoming a gunman. Playing in a band gives a boy pride; he throws his shoulders back, he is somebody. He must live his life in accord with his new position.

The Native Lure of Music

Music, even in its most primitive forms, seems to have an influence upon some portion of mankind. The Salvation Army, for instance, has depended upon banjos, accordions, guitars, tambourines, anything that was musical, to spread its gospel. From this has grown many fine bands, here and abroad, and I was recently honored by having a request from that great woman, Evangeline Booth, to write a Salvation Army March. Of course I gladly complied, and the March will be played by Salvation Army Bands all over the world.

Soap-Soup-Salvation

The Salvation Army’s first medium of appeal, as I have said, is music. Once in Pittsburgh, I asked Gen. Ballington Booth how he got such a firm hold on the down-and-out man and helped him back. His reply was, “First we give them soap, then soup, then salvation, and plenty of it.” We have gotten to depend upon ourselves and our machinery so much that we are in danger of forgetting that there is a God. Nothing brings us closer to God than beautiful music. If you want to know one of the very good reasons why the world needs bands, just ask one of the Salvation Army warriors who for years has searched carrying the Cross through the back alleys of life. Let him tell of the armies of men who have been turned toward a better life by first hearing the sounds of a Salvation Army band. The first time you hear a Salvation Army band, no matter how humble, take off your hat.

Many of my most successful marches were written for special occasions or organizations. The Washington Post was written for the paper of that name in Washington. The High School Cadets was written for a high school in Washington. King Cotton was written for the Lousiana Exposition. Semper Fidelis (Always Faithful), now sometimes known as The March of the Devil Dogs, was written for the United States Marines, and my latest march, The March of the Welch Fusiliers, was written for the great regiment of that name that joined the United States Marines in the protection of Tientsien, during the Boxer Rebellion, when our President Hoover, as a young engineer, was given charge of the all-important matter of caring for the defense and food during that critical time. The march was recently performed by the U.S. Marine Band in Washington, before President Hoover and many of the greatest men of America, at the annual dinner of the Gridiron Club.

Two questions are put to me over and over again. One concerns itself with my name. Years ago someone circulated the absurd rumor that I am a gentleman of alien birth (usually Italian), that when I first/landed in America my name was John Phillipso, and that I added U.S.A. making it John Philip Sousa. I was born in Washington, D.C. My mother was an American of Bavarian extraction and my father, Antonio Sousa, was born in Spain of Portugese extraction. He had served in the U.S. Navy. Perhaps a photostat of my birth record in Washington would convince the skeptical.

Stars and Stripes Forever

The other question has to do with the composition of the Stars and Stripes Forever. Greatly as I have enjoyed other countries, I have always come back to the United States a better American. If you have ever been away from our shores a long time, you know something of the joy that is felt when you are on a boat with its prow pointed for Sandy Hook. The Stars and Stripes Forever was written on the high seas as I returned from Europe. As I walked up and down the decks, this march, which was a translation of my feelings, kept ringing in my ears. I could hear nothing else. When I got on shore I wrote the march. The publishers at first were unenthusiastic, and the purchasers, likewise. Some even sent copies back. The Spanish War came on at that time. A patriotic march was needed; before long this one was heard everywhere, and it has maintained popularity ever since. No one can explain the reason for a success that develops slowly as this did, but it is a fact that many of the most famous works in music have not been successes at the start. Even Bizet’s Carmen was at first a rank failure. Over for million copies of the Stars and Stripes Forever in its various arrangements have been sold, and it has netted me about four hundred thousand dollars.

This article originally appeared in the September 1930 Etude Music Magazine. Reprinted in the April 1991 issue of The Instrumentalist by permission of the publisher, Theodore Presser Company. Our thanks to Arnold Broido.