It is difficult to know which question is more common in the band – the forlorn bassoonists asking why they are there or the band director wondering, what to do with them. As a player, perhaps I can offer some insights that may help foster better music from happier band bassoonists.

The bassoon fills a distinctly different role in the concert band than in the orchestra. The first bassoon in a symphony orchestra plays the important solo passages, while the second bassoon usually provides the critical bass line that establishes the bottom of the chord for the entire woodwind choir. Both bassoons are heard frequently and are indispensable to the total sound picture.

In the concert band, however, the bassoons are used quite differently. The second bassoon of the band does not have nearly the importance it has in the orchestra. In fact, when the Marine Band travels on tour, we use only a first bassoon and find that the second part is seldom, if ever, missed. As a section, the band bassoons are most often used to double other lines. Of course, they have their own moments now and then, but basically they will double the bass line of the tubas and other low brass, the counter-melodies of the euphoniums, the offbeats of the horns and percussion, or the chords of the saxes and horns. In a traditional orchestral transcription for band, such doubling results in a serious endurance problem. Most transcribers will first give the orchestral bassoon solos to the first bassoon, and then both bassoons will double cello and string bass parts, horn and viola accompanying lines, trombone and tuba lines, etc. Although often unplanned, the bassoons usually play from the beginning of the selection to the end with very little chance to get a breather in between. Rest is necessary for a bassoonist because the vibrations of the large reed quickly tire the lip. Orchestral bassoonists get small periods of vital rest here and there throughout the music, but the band bassoonist does not. Even more frustratingly, the bassoons in the band (doubling so many powerful instruments) are seldom ever heard.

The problem then becomes how a band bassoonist can muster the energy to endure the playing of his solo parts as well as the parts being doubled by other instruments. A workable solution could be to establish a principal/assistant system, much like that used by the horns. The first bassoon will play all solo parts. Also, he will play by himself soli parts that may be doubled in the second bassoon if, for purposes of good ensemble and balance, only one bassoon is really needed. Both bassoons will play other exposed sections which sound best when doubled (often marked p or pp). Then, the second bassoon will assist on other parts as the first player rests during, perhaps, a forte tutti section in which the bassoon line is completely smothered by the rest of the band. If more power is needed in a first bassoon solo, the second can temporarily drop his already-doubled part and play along with the first. The goal is to save the lip a bit. Those bands lucky enough to have three bassoons can have the middle man assist both players.

In sections indicated ff, where the bassoons double tubas, trombones, euphoniums, baritone saxes, and bass or contrabass clarinets, the lip can be saved by lowering the dynamic level, perhaps to f even mf. With all the instruments playing, the bassoons just don’t have the power to compete, so why abuse the lip? This system takes some practice, but it will allow both parts to be covered adequately while still giving both players – especially the first – the needed time to rest and recover.

What a shame that most arrangers and transcribers use the bassoon mainly as a doubling instrument where it is covered by the masses, instead of taking advantage of its rich, beautiful tone to add a unique color to small groups of instruments within the band.

Adjust the Parts

Sometimes it can help to alter the parts slightly as long as soli and exposed passages remain unchanged. For example, in the second section of the trio of The High School Cadets March, the bassoon part is formed by combining the tuba and horn parts. The first bassoon part in particular is very awkward and unnecessarily complicated. Why go through all this when the part will never be heard? Just have the bassoon play either the bass line, or the offbeats.

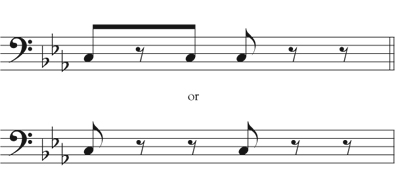

A transcription is also likely to have troublesome bassoon parts if it gives the bassoon a straight copy of a string part. A cellist, for instance, doesn’t worry about breathing as he plays, but a bassoonist does. Some notes in a lengthy part may have to be omitted to allow the bassoonist to breathe. Also, repeated sixteenth notes are easier bowed on the cello than tongued on the bassoon. Consider this exposed phrase near the end of The Flight of the Bumblebee:

At a really brisk tempo, it is just too hazardous for the bassoonist, especially when played staccato. Because it goes too quickly for the double notes to be heard distinctly, have the student play eighth notes instead. The resulting line is much cleaner and more rhythmically dependable.

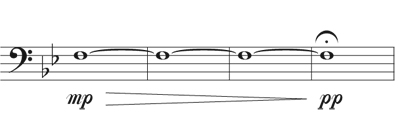

Another example of sensible editing is in the “Polovtsian Dances” from Prince Igor by Borodin. In one section of the band score, both the first and second bassoons are given nearly an entire page of a single pitch repeated over and over in a very fast 68 (in two).

This figure is doubled and relatively unimportant at the beginning; the rest of the band covers it with the theme. However, about two-thirds of the way through, the scoring thins out and suddenly the two bassoons are carrying the figure – now exposed. However, by this time, the tongue has become too fatigued by the rapid figure, so the conspicuous passage becomes extremely sluggish; the conductor wants to keep the tempo moving, but the tongue does not. I feel that it is far better to rest the tongue during the heavy tutti part and save it for the important passages later. Play the figure as:

As the exposed part nears, switch to the printed articulation. The part will come through crisply and accurately, and the tempo will keep moving.

The Whisper Key Lock

The whisper key lock can really be a lifesaver, but few school band bassoonists make sufficient use of it. This small device on the side of the instrument locks the whisper key closed and thereby frees the left thumb to move freely in the lower register of the bassoon. (Some bassoons are equipped with a left-hand lock activated by the thumb, but most have the right-hand type.) This exposed passage in Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Dance of the Tumblers” from the Snow Maiden becomes a breeze once the thumb is freed from upper Bbs and Fs.

Without the lock, the whole thing is a mad scramble, especially if the conductor really wants to go. How much easier the bassoon solo in Percy Grainger’s adaptation of the Irish reel Molly On The Shore becomes with the lock on and the trill fingering used at the point noted below.

The locking device should be added to any school-owned bassoon without it, as it is very much a part of good bassoon playing. The director should ask students to mark on the music not only when to use the lock, but also when to take it off. An upper octave solo could be disastrous if accompanied by lower octave growling caused by a depressed whisper key.

Key Changes Cause Problems

Serious bassoon students will study orchestral excerpts, often committing them to memory, as part of their applied music curriculum. However, they encounter new difficulty when the same solo must be relearned in the band key. Directors don’t always realize how difficult this process may be and that it is not especially beneficial to the bassoonist’s overall development; in fact, performances in both keys tend to suffer. The hours the student has spent practicing the solo from Rossini’s La Gazza Ladra in the original key of G major, will not reduce the time necessary to master the band key of Gb major. Moving the overture to The Marriage of Figaro up a half step from D major to Eb major completely changes the feel of the solo and forces the use of a rather false trill fingering to cope with the opening figure. Stravinsky scored the “Berceuse” from the Firebird in Eb minor. The band key is lowered one half step to D minor. However, in the original key the slurs are much easier to execute because there is less chance of the pitches dropping to the lower octave. (Overblowing the octave can be quite difficult on the bassoon when slurring is involved, but in the original key the chromatic upper fingerings are very different from the lower octave minus the whisper key.) In just the first four-measure phrase, the supposedly easier band key has twice as many notes that could drop to the lower octave. In the example, the pitches marked x are fingered exactly like the lower octave minus the whisper key; slurring makes response on the bassoon difficult for these notes even when flicked or vented for the upper octave.

Many school bassoonists have bewildering difficulty with this solo in the new key. In the Marine Band, most of the transcriptions we play are done by in-house arrangers and usually left in the original keys. It makes it so much easier to learn a major solo passage once and for all.

Tuning and Intonation

Because bassoons in the orchestra control the woodwind bass line, they have a major role in maintaining the pitch, at least as far as the woodwind choir is concerned, but in the band the bassoons lose most of this control since they will probably have to adjust their pitch to the section they are doubling. During an outdoor concert in midsummer for example, brass is quick to heat up and may cause the pitch to go slightly sharp. Because bassoons are often doubled with the tubas and other low brass, the bassoonist must listen carefully and adjust.

Sometimes when a doubled theme is indicated ff, band bassoonists will try to blow much too loud, trying to match the volume of the brass, which causes the pitch to flatten drastically and also produces a most displeasing buzzing sound. In massively scored passages where the bassoon line is heavily doubled, it’s a good idea for bassoonists to play with moderation and not be expected to mimic the power of some of the other instruments.

More school directors question me about intonation problems than any other area, asking why their bassoons cannot play in tune. The most obvious problem, of course, may be with the bassoon and reeds. Truly fine, professional-type bassoons in the public school system are a pleasing but rare sight. However, many of the school models, if maintained and cared for properly, are not bad and should serve adequately. Reeds are always a problem. If there is a symphony or college nearby, directors should contact the bassoonists and try to obtain handmade reeds for their students. Serious students studying privately can depend on their teachers for well-made reeds.

Resonance Keys

Assuming that both bassoon and reed are at least adequate, the bassoonist can attain a higher level of intonation through the use of resonance keys. Several keys on the bassoon can, in addition to their regular capacity, be used to alter the pitch of other notes. One of these is the low Eb key, operated by the little finger of the left hand.

On most bassoons, G3 is usually extremely sharp and often too loud when compared with the other tones. By adding the low Eb key, the intonation will improve. In fact, most bassoonists use this as the regular fingering for the note, although many band method books omit it. The Eb key should also be added to improve E4 and F4. I also add the low Eb key to the basic forked Eb3 and further stabilize the note by also adding the Bb key and the first or second finger of the right hand, whichever sounds best on the particular bassoon. Unfortunately, many method books don’t include these extra keys and some instead present the alternate D# trill fingering as standard.

Suppose your bassoonist has a whole note on C4 in a passage where it is very exposed, very sharp, and unstable. First try adding the low Eb key to the C and then try it with this key only halfway down. It will usually improve the tone markedly. The low Db key is another resonance key that may make the C even better. Also try it halfway down. Depending upon the particular bassoon, one of these combinations should greatly improve the response of the note. These keys also will help improve B3 and Bb3. However, they should be used only sparingly when these tones are very exposed and held for some length of time. Here they are not regular fingerings, but special ones.

If there is a problem with C#3/Db3, try adding the low E key (or, as it is sometimes called, the pancake key) to the regular fingering and it should flatten, soften, and stabilize a bit. Once again, this is a special fingering to be used only in exposed passages and when one has time to get to it. Through experimentation (every bassoon is a little different) you may find that these keys will help other notes to stabilize in pitch. If your bassoonist is drastically out of tune on a long, exposed pitch, experiment with one of these.

The pancake key can be used to stabilize a note during a change in dynamics. As the decrescendo is made, the open F will often tend to stop speaking because of the difficulty involved in controlling the soft tone. By slowly adding the low E key as the de-crescendo progresses, the pitch will keep from sagging and will be much easier to control.

Sometimes a new reed will tend to produce a very flat E3 or open F3. As the reed is broken in, these pitches are corrected through nature. However, if your bassoonist has to play an exposed E and must, for some reason, use a new reed, the flatness can be corrected by adding the G key with the third finger of the right hand. This fingering is for emergency use only and should never become the norm.

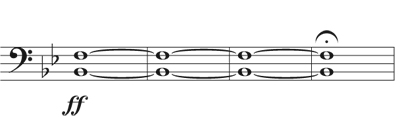

The notes on the bassoon that use the fewest fingers need the most lip for their control. Open F and the E below naturally want to go flat and must be held up by the lower lip. As fingers are added, this lip pressure lessens because the notes are more and more in tune. In an unexposed part such as this, the first bassoonist could simply double the lower part and save his lip quite a bit.

In a situation that calls for a C2 or D2 to be played extremely softly, add the low Bb key (reach carefully around the low B key so you don’t depress it) and these pitches will be much easier to control at a low dynamic level.

An alternate fingering can sometimes solve an intonation problem. Often it will be a slightly different pitch than the regular fingering. If F#3 is sharp in an exposed passage, perhaps the alternate fingering will be a little flatter.

Sometimes doublings with other instruments just don’t work out, even when certain trick fingerings and techniques are used. Although this case is relatively rare, one of the instruments may have to drop out. Once in a while, for instance, a bassoon/euphonium doubling may become a solo for either instrument. It depends upon range, dynamic markings, the musical situation, and the players themselves.

Volume, Projection, Frustration

Few people who have not played bassoon in the band can really sympathize with the utter frustration of having to play an instrument that will rarely be heard at all. In the orchestra, projecting over the full tutti string section can be difficult, but projecting over just the full brass section of the band is nearly impossible. One thing that can help is good positioning. Too often directors put the bassoons in the back row of the band, near the tubas and other low brass. Although it makes sense to group instruments that share the same lines, it is a poor arrangement for the bassoons. They are overwhelmed by the power of the brass and often try to compensate by fiercely overblowing which produces an out-of-tune, raucous line. A much better seating arrangement would be to put the bassoons up front and on the end of a row. Also, keeping the bassoons and oboes together is a good idea. They share similar problems and can give each other moral support. The bassoons should be near the other low woodwinds. These instruments often play similar lines, and it should help compensate somewhat for their lack of brass power by keeping them grouped together, near the front of the ensemble. I recommend seating the oboes in the first row and to the conductor’s right – and the bassoons immediately behind them. The alto and bass clarinets should be next to the bassoons, and the saxophone section should be in the row behind these instruments.

Of course, the ultimate degree of projection, whether in the band or the orchestra, is heavily dependent upon a finely-built bassoon matched with a good bocal and a centered reed. With all this, even a pianissimo has a chance to cut through and be heard. A little bit of buzz in the reed gives it life and is necessary, especially in the band. There is no way a dead reed can make it in the band.

A sound system can be most beneficial to the rather soft bassoons. Outdoor concerts will almost always require the use of microphones if double reeds are to be heard at all. By using the seating plan described above, one microphone positioned near the bassoons will also pick up the other less powerful instruments. A good sound system can make playing outdoor concerts a pleasant experience for the bassoonists.

Final Comments

Two final observations seem to be in order. First, bassoons should never be used in marching bands. Expensive instruments, coupled with delicate reeds and fragile, soft-metal bocals just weren’t meant for movement on the field. Besides, the volume contributed by the instrument in that situation would be negligible at best.

Bassoon students should be encouraged to use a seat strap, and it is also a good idea to have a neckstrap available to support the weight of the instrument when standing. The National Anthem and the school’s alma mater are often played at formal band concerts. When I must stand to play, I make it a habit beforehand to remove the reed from the bocal, put it in my mouth, then stand and put the reed on again. In the cramped quarters of larger bands, such a procedure often prevents the breaking or chipping of valuable reeds. I reverse the order for returning to the sitting position.

Truly, band bassoon playing does have its problems – most more serious than standing up or sitting down. It is no wonder that students tend to become frustrated. Perhaps some of the ideas suggested here will assist you in guiding your bassoon players carefully and letting them know that they really aren’t the neglected band members.