For many years, my focus was on getting students to play with great breath support and characteristic tone quality. My students could do this, and we were successful at adjudicated events. However, when attending concerts at the Midwest Clinic in Chicago, I became aware that there was something different about the sound of those incredible groups. I would look in the programs and see that all of the band members were taking private lessons. So, I surmised that this was the key to the success of these bands. I would be satisfied with this for a bit, but that answer just still didn’t seem right. Upon further reflection, I realized that there was more involved than having students who played well. These bands did not sound like individual students playing with individual sounds; it was as if the musicians were creating a single group sonority. This realization helped me seek out the steps needed to develop a superior ensemble sound and develop what has become a core part of my teaching.

Deciding on Your Sound

The first and most important step to improving an ensemble’s sound is to have a sound model in mind; my approach to teaching changed once I knew the sound I wanted my groups to have. I started by listening to exemplary ensembles such as the Marine Band, the Navy Band, the Eastman Wind Ensemble, and other wonderful ensembles that I admired. As I listened, I noticed that each group had a distinct sonority. My personal favorites are the recordings of the University of Houston Wind Ensemble under the direction of Eddie Green. I was struck by how vibrant and pure the band’s sound was while still possessing a clarity that allowed each instrument to shine through. As soon as I heard Green’s recording of a transcription of Aaron Copland’s Appalachian Spring, I knew that this was the sound I wanted my groups to emulate.

Once you have found an ideal sound, listen carefully to decide what makes that sound appealing, while also determining how to achieve that sound. I read On Teaching Band: Notes from Eddie Green by Mary Ellen Cavitt. It covers Green’s teaching philosophy, including fundamental concepts for posture, embouchure, tone, tonguing, and releases for every instrument, as well as improving an ensemble’s timing and sound. I return to it frequently, taking something new away each time.

In the course of my research, I started to understand more about sound. Sound is vibration, and to create the purest vibration possible, five fundamental concepts must be mastered: posture, breathing, embouchure, tonguing, and releases. The mastery of these fundamentals is essential to the development of a wonderful ensemble sound.

The Enemy of Sound

The number one enemy of great sound is tension, which creates impurities or blemishes in the sound. Eliminating tension begins on the first day of instruction and needs daily emphasis all the way through high school. Below are some strategies for removing tension from the five fundamental concepts in your class.

Posture

Have players strive for balanced posture with feet flat on the floor and knees over the ankles. Keep backs straight with shoulders down and relaxed. Faces ought to be soft with no unnatural creases, and chins should be in a neutral position. Remind students that no part of the body should touch another. Most importantly, ask them to remain still while resting and playing. Watch for tension in the eyes and hands, and encourage players to set posture before setting the height of the music stands.

Breathing

Focusing on a relaxed but full breath from the beginning will eliminate the majority of tension-created problems. Students should avoid forcing the stomach to expand and instead concentrate on letting their stomachs expand as they breathe down and through their chair. Everything should feel natural. As a student exhales, the air should be directional and focused. When I start teaching breathing concepts, I ask students to take a four-count breath. Students should use their eyes to send their air to a specific spot in the front of the room as this will help them to visually focus their air at a faster speed.

Embouchure

The development and maintenance of the embouchure takes vigilance and care. Without disciplined monitoring, bad habits can develop that will make continued musical learning more difficult. Every instrument uses a different embouchure setup, so take time to understand the subtleties of each. Students should be able to describe and demonstrate a proper embouchure setup. They also must understand what vibrates on their instrument to create sound and know the specific vowel sound used to create the characteristic sound for their instrument. Using the proper airstream and correct embouchure will produce a better vibration and result in a better tone quality.

Tonguing

Tonguing is an important area to address for elimination of unwanted sounds. Students need to know the exact tonguing technique and tonguing syllable to use for their instrument; for example, they could use either tOO or dOO. Syllables will be different depending on the instrument, but having students know which to use will help get their tongue in the correct place. For every instrument, the tongue uses a quick motion and should strike the same spot with the same strength every time.The tongue also needs to be in the down position 98% of the time so it does not get in the way of the air. The tongue should only briefly interrupt the air stream, not completely block it. One of the most challenging concepts for students to understand is that the tongue always starts the note the same way regardless of the note length.

Releases

Releases are often overlooked in the fundamentals of sound but can provide great results with the proper attention. The effect created when a group releases a note that reverberates in the performance venue can be moving. Notes can be released either with a breath or by stopping the air. Either way, every student must do it the same way at the same time, and most importantly, the embouchure and tongue must stay still to avoid creating any unwanted changes to the sound. With my middle school group, I prefer that students take a small sip of air on the release so they have a physical activity to place on the release which helps ensure timing. We also talk about defining the beginning of silence (a rest) as clearly as the beginning of a note.

A Plan

To incorporate these fundamentals fully, directors must spend time daily developing these skills with all groups, from beginning to advanced, even if it is just for five minutes. Before and during rehearsals, consider the sound you have in mind, whether you are comfortable in your knowledge of tone production on all instruments you teach, how to best use warmup time to reinforce these fundamentals, and your goals for the entire rehearsal.

I once heard Richard Saucedo say something simple but powerful: “You first have to make your instrument sound like your instrument.” We all want our groups to play in tune with balance and clarity, but to accomplish this amazing sound, students first have to play with a proper tone as individuals. Only then we can unlock the door to playing as an ensemble. All of these fundamentals can be introduced within the first few weeks of a student’s beginning year. The key is for these fundamentals to be practiced daily all the way through high school.

Recommended Exercises

Long Tones

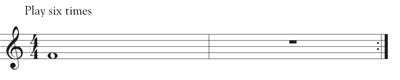

If we have time for just one exercise during fundamentals time, this is the one that we do, and we do it every day. The band plays a whole note concert F followed by a whole rest repeated six times. Used correctly, this simple exercise works on every one of the five fundamental concepts and lets students focus on the beginning, middle, and release of the note. Students must work to remain still and relax during the exercise, including the rests. During the rests, the director can provide feedback and guide student listening.

Articulations

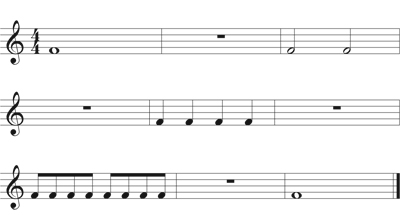

The second exercise that we focus on is an articulation exercise. For more advanced versions, staccatos, triplets, and sixteenth notes can be added. Because this exercise starts on a whole note, the director can quickly reinforce the use of directional air through each rhythm. This exercise is also effective for working on tonguing. The main goal is to make the beginning of every note the same regardless of the note length.

Descending

The third fundamental exercise is commonly known as the F-Remington or F-descending. This exercise starts on concert F, moves to concert E, then returns to F. This pattern continues all the way down to Bb. The primary goal of this exercise is to perform the various pitches with consistent sound and tone quality. Students learn that as the intervals between the notes widen, their air must be more focused to perform all three notes with the same tonal energy. This exercise most closely resembles the music that the students will perform, and is a great transitional exercise to bring fundamental concepts to the music.

Sustained Notes

There is another exercise that may be the most powerful one that we do. Simply have students sustain any pitch for an indefinite amount of time. Students must listen and focus on keeping their tone as steady and still as possible. Without having a specific duration, students will naturally take a more relaxed breath and greatly improve their ability to hold out and complete musical phrases. This exercise builds embouchure strength and is an incredibly easy first step when having students develop their ability to listen across the ensemble. Within the first few days of instruction, my beginning students will sustain the first pitch they learn on their instruments to develop this skill. Approaching the sustained note without tempo and duration, while giving students the freedom to take a relaxed breath when needed, makes this exercise extremely effective.

Levels of Listening

Once students start to perform the previous exercises at a high level with characteristic, tension-free, and resonant sounds, we can start to work on advanced ensemble concepts. The important skill of listening can be a difficult concept for students to grasp. To help guide students, we break down listening into three levels.

Level 1 is listening to self while focusing on creating a vibrant characteristic sound. At this stage, students should be aware of the sound they are making, evaluating whether they are playing with a proper tone, which includes the correct vowel shape. They should also consider whether the sound is open, relaxed, and as vibrant as possible. They should also pay attention to their bodies, considering posture and tension.

Level 2 listening has students monitoring their sound while listening to the two adjacent players (trios) or their section. Students will listen and adjust to match volume, tone, and intonation within their trio and section. Students should focus on their dynamics and whether they can hear the people on either side of them. They should also check whether tone quality and intonation match.

Level 3 listening addresses balance. While paying attention to everything they were listening for in Levels 1 and 2, students will also begin to listen to how their sound fits inside the sound of the tubas. If a student can hear the tubas while playing, it creates a natural balance that is the foundation of a mature ensemble sound. Every director dreams of having a perfect instrumentation, but this is not always the case. If your group has no tubas, have students listen down to the lowest voice in the ensemble. These concepts will still help your group improve their overall sound.

The first three levels of listening are the foundation of developing a superior ensemble sound. However, this may not help us hear the most important part of the song – the melody. To help teach the three levels of listening while still balancing to the melody, I developed Level 4 listening, which consists of teaching students how to balance to an instrument other than the tubas. While students perform the long-tone exercise, I will call out a section, which will then change from a concert F to a concert G. By playing a dissonant pitch, the ensemble can more easily find that section’s sound and balance to it. Students will learn that they have to make decisions on how loud to play to make the concert G balance with the concert F. Rotate through each section, including percussion, so students can learn to listen around the entire ensemble.

Once students are comfortable listening for the concert G, the next step is to do the exercise again, only this time when I call out a section, they remain on the concert F. Without the cue of the dissonant sound, students will need to listen intently for that section’s specific timbre to attain the proper balance. For more advanced groups, you can call out two sections, who will then play the third and fifth of a major chord respectively, creating a major triad. The goal will be to get the chord to speak while maintaining a fundamental sound. Level 4 listening helps those moments in a musical selection where a melody or an important note in a cluster chord is scored in just a small number of players.

Level 5 listening helps students to focus on the venue in which they are performing. We often run into situations in which we have to perform in an unfamiliar hall. The focus of Level 5 is to make the performance space respond to the sound of the group. This will help students quickly gain confidence in any performance situation. By doing the long-tone exercise while students focus on playing with a full vibrant sound, the performance space should respond by creating a ringing sound (reverberating) in the hall after each release.

Variations on the Basics

Once your ensemble can perform the basic exercises with the desired sonority and resonance, it is time to modify them to focus on skills needed to perform vibrant harmonies. In these modifications, the aim is to hear the harmonies being created clearly while getting the notes to react with each other. These variations are also a great way to mix up the basic exercises to keep students engaged and interested. Some examples include:

Long Tones and the Levels of Listening

Build the long-tone exercise through the various levels of listening. Start with Level 1 listening, then Level 2, followed by Level 3. Use the rests to help guide student listening and reminders. Remember to include the Level 4 exercise from earlier.

Long Tones and Balance Training

Start the long-tone exercise with the tubas, then build your group from the bottom to the top. Verbally cue in the next section that you want to add to the current sound during the rests until the entire band is contributing. As in level 3 listening mentioned above, students will need to fit their sounds inside those already playing. You can also start this exercise with just first chair players, then slowly add additional musicians. Focus on maintaining the sound and balance as the group becomes larger.

Articulations with Harmony

After students have a strong grasp on articulations, add harmony to the exercise while asking students to keep the chords vibrant and clear. While the brass and percussion play the exercise on concert F, the woodwinds can play the exercise while ascending all the way to the perfect 5th. Play the exercise again and have the woodwinds play the concert F as the brass and percussion change notes.

F-Descending with Sustains

While working on the Remington exercise, have the brass and percussion sustain a concert F while the woodwinds perform the exercise. Have students listen to the middle note and how it reacts to the sustained concert F. Then have the sections switch roles.

Sustains with Harmony

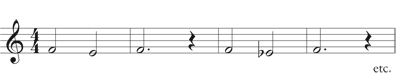

The final example that I will share is a great way to let students work on listening and understanding harmonies. Start by splitting your group in half; this can be woodwinds and brass or high and low instruments. Have one group sustain concert F while the other group slowly moves up and down the first five degrees of the F major scale. The goal of this exercise is to get the sounds to vibrate with each other while also working on intonation. This is a great opportunity to introduce the concept of just tuning versus equal temperament tuning. To get the third and fifth of the chord to truly resonate, the third must be lowered by fourteen cents and the fifth raised by two cents. The more we work on this concept, the more the students can start to bring that skill to our performance music. The great thing about the exercise is that it can be done in any key.

Fundamentals and

Performance Literature

Once students have a good grasp on the fundamentals, it is time to bring that knowledge to the music. Remember, ensemble sound starts with you. It is crucial that you take frequent opportunities to put the baton down, step away from the score and off the podium, and listen to your band. Avoid any habits, such as singing along with your band, which might interfere with critical listening. As you rehearse, pay attention to whether the group sounds the way that you want. If not, fix it. There is nothing wrong with stopping what you are currently working on and returning to the basic long-tone exercise to focus students. The sound of the group must always come first.

When approaching performance literature, be creative with how you rehearse. Use the fundamental exercises as a foundation for rehearsing the music. For example, create sustains in the music that require students to work on phrasing. Use a drone where appropriate to help students to listen for intonation. Have small groups play certain sections of the music to help establish ensemble sound or set style. Start with your first chair players, then rotate to make sure everybody has an opportunity. You can also split your group into three or four small ensembles with every part represented. This is a great way to listen to more students and check accountability.

One of my favorite rehearsal techniques is to play a section of music in the style of a chorale. This allows students to work through the technique and the adjustments necessary to hit the center of every note, which also improves the overall sound of the music. By working on sustains, students improve airflow, relaxation, and phrasing. On faster technical passages, have students go note by note slowly so they can learn what it feels like to change pitches while keeping the airflow constant. Students tend to chop the air up as they change notes instead of keeping the air constant, which also makes the technique more difficult. Students also tend to rush faster passages. Help students combat this by having them just finger along with the music and work to get their fingers to click perfectly in time.

Student Engagement

While these fundamental exercises can do wonders for your band, they can easily become stale to students. One way to keep students engaged is through higher level questioning. Your musicians must be able to tell you how to fundamentally play their instruments. They should be able to describe what they are hearing. If we are always the one telling our students what we want and what should be improved, our students will begin to shut out what we are saying. You can increase student interest by frequently asking them how to improve problems they are noticing. Be creative with your questions, and do not be afraid to make them think. Students love to take ownership over the way that the group sounds. For a quick check for understanding, I will often have students show me their thumbs to see how well they understand. Thumbs up means “I understand completely,” thumbs to the side means “I think I understand but might be wrong,” and thumbs down means “I still need some more help.” The important thing to remember is that your students want to sound good, and they can tell when they are starting to improve.

Final Thoughts

By focusing on these fundamental exercises while working to remove any tension, my band’s ensemble sound and musical expression have improved immensely. As my students and I continue to improve our fundamental ideas, more layers continue to reveal themselves. By making these fundamental concepts a consistent part of rehearsals, the level of performance will begin to improve. I challenge you to start your own quest to find your ensemble sound. Remember, it’s fundamental.