Derek Gipson is the brass caption head for the Bluecoats drum and bugle corps. “As caption head, I am mostly responsible for coming up with the technique program. I write the day-to-day lesson plans and assign what the other brass teachers on staff are to do that day. One of the secrets of success at Bluecoats is that I record the group every time we do a run-through of the show. I use a portable but decent recorder to get a good-quality recording rather than try to pick everything up on my iPhone. At night I listen to the recording while I study the score. From there I make notes and come up with a solid lesson plan for the next day. That time is the most important part of my day; listening, score study, and planning are extremely important.” Gipson, who earned a music education degree from Louisiana State University, runs the brass program with Dave MacKinnon, a former Bluecoats caption head who is now brass supervisor. “MacKinnon has been around the Bluecoats since 1994. He brings an experienced set of ears and offers many great suggestions about scoring and musicality. Dave and I work well with brass arranger Doug Thrower, who has been with the Bluecoats since 1992.”

How do you warm up the Bluecoats brass?

Every day we start with a session called breathe-sing-buzz. We use ideas from The Breathing Gym by Pat Sheridan and Sam Pilafian as well as supplemental exercises that other staff members and I have learned over the years. We don’t do these with instruments or in any formation.

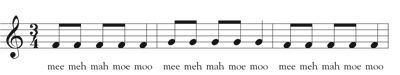

This is followed by singing. We use a tuner to go up chromatically instead of a piano, but the singing warmups are similar to what a choir might use, starting with exercises on vowels (mee-meh-mah-moe-moo).

In using these as a warmup, students learn how to match these vowels, which applies to getting a blended sound. For playing, the vowel shape we teach at Bluecoats is ah in the throat and oh in the mouth, and we realize that sometimes upper register high brass may have to change the oh in the mouth to something smaller, but we try to get as open a space in there as possible. Students won’t be playing much with an ee sound, but the idea of getting a good, blended choral sound is important.

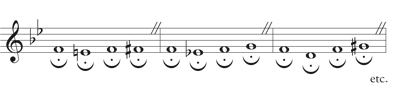

We also sing scales and arpeggios and will harmonize scales and modes. Singing in harmony helps to match pitch and give direction to both the line itself and also the energy through each pitch. It is easy for vocalists to go flat if they do not concentrate on the entire note. One exercise we frequently use is to go up a scale together in unison, and on the way down, one group stays on the top note, another stops on la, another stops on fa, and then, as the last group goes from re to do, la goes to sol and fa goes to mi.

We do that not just in major and minor scales, but also in modes. Having students know where the half and whole steps are in any given key is a beneficial skill, so we do a fair bit of ear training with these.

.jpg)

I also use simple Gregorian chants, which are great unison works that do not require accompaniment. Chant music lends itself well to proper phrasing and giving direction to the line, as well as matching pitch and blending. They are a good way to sing authentic music without extensive vocal training, plus students enjoy them.

Vocal warmups are an excellent way to get students to focus. I have also noticed that doing these warmups can be emotional for the members who are aging out; there are some teary eyes doing the vocal warmups the last couple days of the season.

After vocal warmups, we buzz mouthpieces. We mix buzzing exercises up quite a bit, with different staff members rotating in and offering different perspectives, but commonly used exercises include sirens, long tones, and pitch matching. Over the past few years, Matt Stratton, the assistant caption head, has developed a technique called magic buzz point. Players blow air through the mouthpiece with a slightly wider than normal aperture and then gradually let the lips wrap around the air until a buzz forms on its own with as relaxed a face as possible. The point at which a buzz forms is the magic buzz point. It is a way to get a natural embouchure without tension. This works especially well with students who have tight sounds or tight apertures. If they start with a more open aperture than necessary and let things happen, the sound just starts without them trying to force it. This also usually produces a more resonant buzz.

The next step is to go to the horns. Most of our warmups are done in a circle, in integrated instrumentation. Trumpets aren’t all together. We put trumpets next to tubas for intonation reasons and also to encourage trumpets to play with as round a sound as the tubas. We also put the second euphonium voice next to the tubas because the two instruments often play in octaves. Integrating instrumentation can expose weak spots and make it easier to help people who are producing a different sound than everybody else or not playing up to the same level.

On the horns, we start with long tones, and I use a number of different long tone exercises. Variety is a way to keep warmups interesting. In drum corps, the difficulty is balancing the fact that everything, including warmups, is memorized with having enough exercises in the manual to keep these good musicians interested. Drum corps members today are much different from when I marched. They are a lot more talented. I want to keep them interested without having them memorize so much material that I have to shift the focus from talking about the concepts behind the exercises to making sure they have everything memorized.

In addition to Remington exercises, I use one by James Stamp. I like this one because it can be played with a sense of phrasing and connectivity through lip slurs. In addition, the whole step head start into the lip slur at the end makes it a little easier.

I also use a long tone exercise by Bill Adams, who was a somewhat esoteric and philosophical trumpet teacher. We tell students that the number one indicator of whether they are doing it right or wrong in getting the right sound is not how it feels or what the embouchure looks like, but how the instrument sounds. The most important muscles we have are our ears. My trumpet teacher was a protégé of Adams, and he would occasionally tell me I was thinking about the wrong end of my instrument. We give instructions about the throat and tongue placement, but it is all for the purpose of getting a better sound, and that should remain the main focus.

In the Bill Adams long tone exercise we use, all the notes have fermatas over them. Often in drum corps we do things in tempo and while marking time, and sometimes students need a break from that to relax and focus on getting a good sound. I especially like to use the Bill Adams exercise after a stretch of long days. We work on just getting great sounds like they would in a practice room at home.

After that comes air flow studies. The concept is maintaining a sense of resonance and follow-through with the air while wiggling the fingers. When brass players start wiggling the fingers or using the tongue, they sometimes change the way the air flows or move the embouchure because they are trying to control the change of pitch, but this is unnecessary and detrimental. The first air flow study we usually do centers on concert F.

Another air flow study we use includes lip slurs. The beginning still works around half steps, and it expands from there. All of them feel very relaxed to play, and they are a good way to get a free buzz going.

After these we do lip slurs and articulation exercises. Brass parts for this year’s show include double tonguing, so I have also chosen some double tonguing exercises from the Arban book.

We also play chordal studies and chorales and make a point of playing these at louder volumes to work on projecting a good sound. High school bands aren’t going to play as loud as a drum corps, but in my experience, once you get into orchestral music, brass players will need to play as loudly as they do in drum corps. We have experienced this in the Bluecoats. We were commissioned to play a Khachaturian piece with the Canton Symphony, and the conductor kept asking the trumpet players in the drum corps to play louder. He was right, too; the Bluecoats trumpets were not loud enough to match the orchestra. Sometimes there is an idea that drum corps teaches students to play too loudly or to play loudly the wrong way, but we work to project with the best possible sound.

During camps that warmup may take 90 minutes. By the end of spring training it will be about an hour, and once we get on the road it is usually less than an hour. As we get on the road and the available time each day diminishes, sometimes there is just time to warm up before going straight to full-corps rehearsals. As the time for warmups becomes more compacted, we will only hit on one or two things from each of those categories.

What are the keys to keeping the best possible sound while on the move?

All of our visual teachers talk plenty about separating the upper body from the lower body and playing with good posture. The breathing exercises we use emphasize efficiency and proper airflow and relaxation but also filling up. The more you fill up your body and the instrument with air, the more there is a sense of cushion between the feet and the upper body. Much of that comes from using your air correctly as well as good posture. This is easier said than done, and mostly it is learned through experience.

We try to avoid sitting in an arc and playing. Early on, when we are primarily talking about such concepts as vowel shape, musicianship, and pitch and interconnecting these, which takes our full concentration. However, once we get through that stage, it is important to get on the field, get in the drill, and work on the music that way. We rarely stand still and work on show music. We play on the move as brass alone, and even in sectionals; the trumpets will practice their music in a sectional while going through the drill at the same time.

We also do some technique exercises on the move. Members learn circle drill exercises in marching practice. We march straight in toward the center for eight counts and then back out for eight. We also go around the circle for 16 counts, then back around for 16 more. We do variations of these combinations so students get practice marching straight forward with the intervals getting closer, marching straight backward with the intervals spreading, and then having to march to the right and turn the shoulders to the left when going around. Students have to keep their shoulders and bell turned toward the conductor when marching around the circle. This seems simple, but it can be difficult even for people with marching experience to do it well. Students have to pull the shoulders around, look strong, and still not have the interval fluctuate while playing with a good sound.

Circle drills like this have been around for years, and many drum corps add long tone exercises to the circle drill so marchers are doing something challenging visually for them and overlaying the responsibility of playing on top of that. A good way to check the sound is to have students play the exercise standing still and immediately follow it with playing on the move and let students experience the difference in the sound.

The show music in the drill gets more secure as members get the long tones in circle drill more secure. We spend quite a bit of time in the circle and spread apart. We do not use a double circle; there is no one behind another player. This makes it easy for people to hear themselves and for staff members to offer encouragement or guidance. When students get a beat in their sound from marching, it is often because they are not letting the air flow through their throat in a relaxed way. They are constricting something, and any time there is tension, especially in the throat or shoulder area, the feet are going to jar the tensed part of the body. However, a more relaxed and properly positioned upper body is going to have some cushion there.

We also play in a parade block, although this is primarily for working on the show music. So much of teaching is isolating different skills, so we take away having to change directions or pay attention to drill counts and just march forward in a block while playing our show music. This does a great deal of good. We call it tracking, because years ago the corps would do this on the track surrounding a football field. After 30 minutes of working on the music in a parade block, we put it back on the field in a drill, and the sound is much more confident and controlled.

One surprisingly effective strategy for improving the sound is to play everything at piano, so students can focus on strictly controlling their bodies. It is difficult to control everything while moving around and playing softly, and performing the show softly makes it feel easier when we go back to written dynamics.

What are some other rehearsal tips you would recommend?

We have long days and need to preserve students’ strength, especially if there is a show that night. We have several good strategies for keeping students from blowing their chops in rehearsal. Sometimes we sing on the move or just blow air through the instruments and finger notes. We have also run the show with members changing every note of their music to concert F. Sometimes we do what is called bopping, where we only attack the beginning of the notes. We also run drill with just one section playing. This is especially useful for finding hidden errors or weaknesses in the show, and it gives the other sections a bit of a break.

What are the secrets to getting the best possible sound?

Many band directors faithfully record their concert bands, and I would like to see more do the same for their marching bands. When I critique a marching band, sometimes I get the sense that that same level of dedication isn’t happening. Attention to such details as knowing who plays which line at what time and at what dynamic is what will help directors take a marching band to the next level.

As an added bonus, if time is taken in marching rehearsals to teach students how to pay attention to melody, countermelody, and accompaniment and how to know how important their part might be, they will already know to listen for such things when concert band kicks into high gear.

Additionally, just as what should matter the most to brass players is the sound that comes out of their instruments, what should matter the most to marching bands is how they balance the ensemble sound. One technique that I have found works well for marching band or drum corps is to assign all the dynamics a level; level one is piano, level two is mezzo piano, and so on, up to levels six or seven. I do this because dynamics are relative; a forte in a brass quintet is going to be different than a forte in an orchestra. However, although dynamics are relative, the levels are not, and I define these for corps members. If someone is behind the second hash, they might play at level five while everyone else plays at level four. The aim is to make what the audience perceives match the dynamic written in the score, but depending on staging, voicing, and the nature of each part, I might assign different levels based on numbers to students to produce that perception. There is something about the numbers that helps students understand. “My page is marked mezzo forte, but I have to play at level two, which is softer, because I’m right in front and not playing melody.” It speeds up getting good balance and blend.

What aspects of performance do you reiterate the most over the course of the season?

I am most proud of our resonance, projection, clarity, and blend that help make up the signature sound for which the Bluecoats brass are known. However, once we get that going, we end up talking about timing for much of the year. This is one of the most difficult parts of teaching marching. We ask students to use their ears all the time to match tone, pitch, and style, and then we tell them to quit using their ears to play together because the speed of sound plays a role on the football field. If someone plays while standing right on the front sideline at the 50-yard line at the same time as somebody standing on the second hash on a 25-yard line, the player on the 50 will sound as much as half a beat ahead at 120 beats per minute.

Often we use the conductor or drum major to adjust for students. If there is a group that needs to enter in the far back. We will conduct more ahead of the sound to bring them in. Nevertheless, even with that kind of help from the drum major, players still want to use their ears. Students have to ignore what their ears tell them and go right with the drum major’s hands. It can become rather scientific as we talk about the speed of light versus the speed of sound.

Half of our music score is percussion, and while they work hard on getting an excellent tone quality, they are mostly rhythm. If the brass can’t play together with them, it affects not only the music ensemble but even the percussion score, especially if we’re playing something without the battery percussion. In addition, a slow, ballad-style piece might be mostly brass and front ensemble. If the brass and the drum major are inconsistent with each other, the front ensemble has difficulty playing together with the brass.

When you judge marching bands, what comments do you make the most often?

I do more judging on the field than from the stands, so I often listen to individuals and smaller groups. I would say that the most common thing I notice is marchers not finishing phrases or blowing through to the backs of notes. I want to hear a resonant sound all the way through the notes. Playing a note is like throwing a ball. Just as you want to continue the arm movement after you release the ball, brass players have to continue the air acceleration after they start the note.

Often this comes up in long notes. Imagine two double whole note chords. Counts 7 and 8 of each of those will either have half the ensemble drop out to breathe or they at least stop supporting; you can see them thinking about the next note rather than staying resonant on the first note and connecting it to the second.

One way to get around this is with careful staggered breathing. I frequently tell the Bluecoats to breathe anywhere except the barline on long connected phrases. You cannot make a chord resonate just by playing loudly, it also takes sustain. This is especially true on counts seven and eight or 15 and 16.

Something that often adds to the difficulty in these situations is when the drill has a direction change. Not only are students thinking about the next note, they are also thinking about a difficult direction change, when they may have to go to a much bigger step size. They either all breathe on the barline or just stop supporting the note. In critiques, I suggest to band directors that they might do well to define a breath point in these troublesome spots. This way everybody takes a breath together. You keep a full sound on count 15, then everyone breathes on count 16. This presents a new challenge because you have to work on cleaning a release, but sometimes that is the lesser of two evils, especially when the other option is a phrase end that just doesn’t sound good because too many students are dropping out to take a breath.

What difficult situations do you see marching bands get themselves into?

I have seen plenty of intermediate bands attempt advanced corps-style things, whether it is fast tempos, large step sizes, or scoring that is way too individualized. If a band has three trumpet parts for three trumpet players, it might be too much.

The downside of trying for more than students can handle is that students and directors are not rewarded for their hard work – and it is hard work to do what the world class drum corps and top marching bands do. If a group tries to emulate this but lacks the capability to perform well at the highest levels, the scores will not be as high as they might for a group that attempted something easier and handled it well. The analogy I use is that a three-point shot in basketball doesn’t count unless you make it. It is better not to overstep your abilities. Build a program slowly.

What is your hope for the future of marching bands?

I want people to sound good – even the ones I’m competing against. For years, the Cavaliers had a great teacher named David Bertman, and he had the same mentality. He came from the band world rather than the drum corps scene, switching over when the corps went to Bb instruments. He coached the Cavaliers to a specific sound, and they were successful with it. Bertman was always very open with other people about how he did it. He did not care who won, he just wanted everyone to sound their best. I have tried to emulate that.