Drill, body choreography, and color guard are important, but marching band is ultimately about the music, and the musical performance of our students should reflect that priority. At every show I have judged, including five state championships, evaluation of the music made up more than 60% of the score. Even the greatest visual choreographers and drill designers agree that the construction, scoring, and content of the music is the top priority. DCI Hall of Fame visual designer Gary Czapinski gave a lecture at the 2009 Midwest Clinic to an audience of over 500 people, only one of whom would admit to creating marching formations before the music. In 2007 I was part of a panel discussion with Michael Gaines, one of the most sought-after drill writers in the country, where he confirmed that he does not write drill before he hears the music, contrary to popular rumors. This precept that the music has to come first, has been affirmed hundreds of times by experts from across the spectrum of the marching band and drum corps world.

Drill, body choreography, and color guard are important, but marching band is ultimately about the music, and the musical performance of our students should reflect that priority. At every show I have judged, including five state championships, evaluation of the music made up more than 60% of the score. Even the greatest visual choreographers and drill designers agree that the construction, scoring, and content of the music is the top priority. DCI Hall of Fame visual designer Gary Czapinski gave a lecture at the 2009 Midwest Clinic to an audience of over 500 people, only one of whom would admit to creating marching formations before the music. In 2007 I was part of a panel discussion with Michael Gaines, one of the most sought-after drill writers in the country, where he confirmed that he does not write drill before he hears the music, contrary to popular rumors. This precept that the music has to come first, has been affirmed hundreds of times by experts from across the spectrum of the marching band and drum corps world.

When selecting music, directors have some choices to make. Options include purchasing an existing arrangement of music familiar to the audience, hiring someone to create a custom arrangement of similar music tailored to fit the band. Other possibilities include buying a show composed specifically for performance on the field from a company specializing in marching band shows or hire someone to create an original composition for a band to perform.

Purchasing an existing arrangement of music familiar to your audience from a music publisher is by far the least expensive route. The relatively low purchase price of each piece includes all licensing fees as well as resolution of all legal hurdles such as obtaining permission to arrange and compliance with copyright laws. The drawback is that many bands purchase the same arrangements and end up performing the same music in competition. Some published arrangements may not fit the instrumentation of a band or make the most of the strengths of your program. Most published arrangements must fall within industry guidelines for scoring combinations, ranges, key signatures, and technical difficulty to get published in the first place, some of which may or may not be the best fit for your band.

Creating a custom arrangement of existing music can solve some of these problems, in that the arranger does not need to consider the commercial viability of a work, only the needs of your program. If a band has a strong soloist or two, the arranger can showcase these players. If any particular section is substantially stronger than the others, the arranger can write more interesting or more difficult music for these sections to increase the musical effectiveness of your program, which can also offer inspiration and opportunities for those who design the percussion, drill, and color guard portions of your show. The primary concerns with this approach are the cost of the arrangement, the time required to complete the arrangement, and the legal requirements that must be fulfilled.

Creating a custom arrangement of existing music can solve some of these problems, in that the arranger does not need to consider the commercial viability of a work, only the needs of your program. If a band has a strong soloist or two, the arranger can showcase these players. If any particular section is substantially stronger than the others, the arranger can write more interesting or more difficult music for these sections to increase the musical effectiveness of your program, which can also offer inspiration and opportunities for those who design the percussion, drill, and color guard portions of your show. The primary concerns with this approach are the cost of the arrangement, the time required to complete the arrangement, and the legal requirements that must be fulfilled.

For any published or recorded music for which copyright is still in effect, the law is absolutely clear that permission must be obtained to arrange the music. This permission may come from the publisher or agency acting on their behalf. Obtaining this permission almost always includes payment of a fee, which can vary greatly based on the age and popularity of the music as well as practices of the copyright holder. Hal Leonard, Alfred, and the Harry Fox agency are some of the largest and most common agencies from which you can obtain permission to arrange and pay the appropriate fees. It is wise to investigate whether permission to arrange is even available before going any further into the design process. Some composers and performers will not allow their music to be arranged for any medium. Others have placed such high fees on obtaining permission to arrange that the licensing fees may cost more than the arrangement. Factor these costs into your budget for designing your show.

Many prominent music publishers, as well as a growing number of web-based companies, now offer marching band arrangements designed specifically for the field. The advantages of purchasing original music from a publisher are much the same as purchasing an arrangement: the price is often very reasonable, the parts can be delivered in a matter of days, and all legal hurdles have already been resolved. The potential disadvantages remain the same, in that this show may or may not fit the instrumentation of your band or its strengths and weaknesses. It may also be difficult to find a show that captures the imagination of the students, the community, or the rest of your design team.

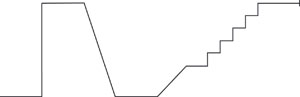

This graph of the first movement of a marching show depicts

high and low points as well as builds and drops in intensity.

For their marching band shows, many directors now commission an original composition, one that will highlight the strengths of their program as well capture the imagination of the band and community. In this case, no permission to arrange is needed, because the music is original. There are no licensing fees to pay, either. Ideally, the composer and the director should have several conversations to discuss ideal ranges for each instrument, how many players will be on each part, and any other unusual facts about the band. The Instrumentalist published a fascinating article about Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Michael Colgrass in January 2009, in which Colgrass described the use of graphic imagery to guide the process of creating music. I have adopted this model when composing music for marching band with great success.

In consultation with the band director, I make a graph of each section (often referred to as a movement) of a marching band show. We determine the overall length of time for each movement, as well as the placement and duration of musical high points and low points and the exact time that each occurs in the movement. For instance, the graph below shows the first movement of a show I created for band director Vic Scimeca at Wheaton-Warrenville South High School in Wheaton, Illinois.

First, we developed a timeline for the first movement. After discussing the musical strengths and personnel of his band, we identified potential soloists and chamber music combinations to use during the show, and placed these on the timeline as well, repeating this process for each movement and making sure that the high points of each movement made sense within the overall contour of the show. Further refinements were made as the members of our show design company, began constructing the percussion parts, drill, and color guard work. For instance, our percussion artist asked if we could add a few measures at a given point to allow him to more fully develop a thematic fragment in the percussion parts. Conversely, at another point, our drill designer asked to take a couple of measures out to accelerate the resolution of a drill idea.

By staying in frequent communication, all of these changes were easy to incorporate to produce the best possible show. Further changes were made once the band actually starting learning the drill and putting it all together. This type of creative interaction between the designers of all the elements of the show is one of the principal advantages of hiring one company to create a show. If all of the elements of a show are well coordinated, then the director has more time to focus on the musical requirements.

Above all, be realistic when choosing music. It is amazing to hear the Marion Catholic High School Band play the Shostakovich Fifth Symphony on the field. However, if a woodwind section is unable to perform blazing runs and arpeggios for seven minutes, perhaps that is not the best choice for music. As a judge, this is one of the most common problems that I observe in bands across the country. Many groups are performing music that is simply too hard for them. H. Robert Reynolds, one of the most respected figures in wind conducting, warns against this practice. In essence, he states that if the band cannot perform the notes and rhythms at a recognizable level during the initial sight-reading, then the opportunity to teach intonation and phrasing will never occur. Despite the length of the marching band season, this principle holds true. If the students are struggling to play the music when seated indoors, the music will not get better when you add drill. Musical challenges are compounded in marching band because of the dispersion of the players across the field, the often intricate nature of the percussion parts, and the shifting listening environment due to the movement of the players within the drill. Weather conditions, stadium construction, and the presence of an audience can make musical performance in marching band even more difficult.

I do not advocate reducing marching band music to the lowest common denominator. On the contrary, I hope that by encouraging directors to carefully select or create music to fit the skills of their group, the level of higher-order musical skills such as intonation, characteristic tone quality and beautiful phrasing will actually increase. The single most important element in a field show is the music. Select it with great care. It is completely appropriate to consider whether or not a specific piece of music fits the skills and instrumentation of your band, as well as the opportunities it offers for points of arrival and climax, as well as points of rest and calm. A balance between these elements, enhanced by the drill and guard work, is the essence of a great marching band show.