Snare drum rolls are one of the most important – and perhaps least understood – components of percussionists’ development. Students must learn to play rolls accurately and musically according to such parameters as style, tempo, and dynamics. Here are techniques for building fundamental roll strokes, combining those strokes into sustained rolls, and applying musical and technical decisions to play the right roll at the right time in the best way possible.

Percussionists use four roll types for general playing: single stroke (one note per hand with alternating sticking); double stroke (two notes per hand); triple stroke (three notes per hand); and multiple bounce (more than three notes per hand). Single stroke rolls are typically used on instruments with a naturally sustaining sound, such as timpani, suspended cymbal, or marimba. Because these instruments have a relatively long decay when struck, rapidly alternating single strokes are quite sufficient to sustain long notes.

The sound of a snare drum decays quickly, and even if a player can execute very rapid and even single strokes, the sound of the snare drum will still leave slight gaps in the sustain. Developing a strong single stroke roll on the snare drum is worthwhile for fast rhythmic passages and for application to other instruments, but the main ways to sustain longer notes are the multiple bounce, triple stroke, and double stroke rolls.

Developing Three Roll Types

Multiple Bounce Roll

I generally guide students to develop multiple bounce strokes first because playing them is generally easier than double or triple strokes for beginners. Exploring the physical technique of these strokes also introduces students to the extreme opposite of single strokes; they will play as many bounces as possible per hand versus only one note per hand. Once students have developed the ability to execute an undefined large number of bounces in each hand, it is much easier to strip away some of those bounces and practice playing exactly two or three later on.

The best way to introduce multiple bounce strokes is simply to model them. I play in alternation with students, on only one hand at first, so that they are focused on the sound I am making and trying to copy it exactly in terms of dynamics, duration, and spacing of the bounces. Using the natural rebound of the stick and guiding it just the right way will produce a gradual buzz sound as the stick moves closer to the head with a single wrist motion. I like to use the analogy of bouncing a tennis ball on the ground with a tennis racket and gradually pushing the bounces into the ground until they come to a stop. As teacher and student alternate buzz strokes, they will naturally fall into a repetitive, even trade in which constant repetition of the model sound gradually produces two equal sounds between the two players. Once a good buzz sound has been established, move to the other hand.

While developing buzz strokes, students will likely recognize the gap between their strong hand and weak hand, assuming they are not naturally ambidextrous. Students should come to terms as quickly as possible with this physical discrepancy, and take steps to overcome it. I usually pose a series of questions during instruction, asking them when they think they developed a dominant hand, and what they may be doing daily that increases its dominance. They often reply with “writing,” “texting,” “eating with a fork,” “operating the computer mouse,” and “unlocking my front door,” for example. All of these tasks require dexterity with small muscle groups, the very ability needed for consistent buzz strokes on a snare drum. I then encourage students to do all of those tasks with the other hand regularly; many of them will be surprisingly challenging at first, but switching hands will be well worth the time and effort.

Students can also use the discrepancy between strong and weak hands directly as a learning tool. If the dominant hand is playing a solid buzz sound right away, have them use it as a model for the weak hand. Guide them to play several buzzes with the strong hand, noting the feeling of the fingers on the stick, the contact with the drumhead, the physical control of the rebounds, and the lift when the buzz is finished. They can watch, listen to, and feel the details of each buzz and transfer these to the other hand. The strength of this approach is that all of it is happening within the student’s body and mind, rather than relying on an external model. This strategy can apply to any technical problem involving the two hands.

When students have developed a good sound on each hand in isolation, they can begin to alternate hands. I remind them to keep the sticks down in the drum as much as possible. Creating a smooth, sustained roll from alternating buzzes requires the sticks to move unequally up and down. In other words, the stick does not move up and down in an equal rhythm, but in a lopsided rhythm favoring the downward motion. I use the metaphor of allowing the sticks to come up only for air, and then go right back into the roll sound. This purposefully imbalanced hand motion can be difficult to develop; to solve it, have students practice isolated buzzes at faster and faster tempos, while maintaining the full length of the buzz. They should notice that their sticks reset to the up position with a quick motion, and dwell on the buzz as long as possible.

Triple Stroke Roll

As students increase the speed and dynamic level of the buzz roll, they will reach a point where the buzzes start to sound choked and separated. At this point, the buzzes are occurring so fast and loud that the bounces are being squeezed into a space that cannot contain them comfortably. This situation calls for development of the triple stroke roll, which creates more space between each bounce by playing only three bounces on each hand.

Students can again start with isolated hands, developing the sound of triple strokes consistently. The rhythm of these strokes should be a precise, even triplet. Start with the buzz strokes they have mastered, and guide students to gradually shift into strokes that contain only three bounces, spread out evenly across the duration of the stroke. As soon as they are able, they can begin to alternate hands to create the sound of constant triplets. Pay close attention to the spacing of the three notes on each hand, so that the triplets run precisely into one another in alternation, creating a completely consistent stream of notes. Each triplet should consist of rebounds, not individual strokes; in other words, the wrist moves only once for every triplet.

Because the triple stroke roll is used primarily for fast, loud passages, be sure to encourage students to practice them that way. The muscular stamina required to do this may be somewhat surprising at first; students may need guidance in maintaining their muscular health, including frequent breaks and knowing when to stop for the day. Just as with building a brass embouchure, pushing a player a bit past their current muscular development is necessary for productive practice, but pushing too far can have damaging results. A warm feeling in the forearm muscles is fine, but a sharp persistent pain is not.

When students have developed a controlled, sustained triple stroke roll at a loud dynamic, they should begin to experiment with when to switch from a buzz roll to a triple stroke roll. A crucial consideration in this decision is that, generally speaking, the louder the roll the faster the alternating hands. For example, at an extremely soft dynamic one can play very slow sustained buzz strokes, drawing out the maximum number of bounces in each hand. As the dynamic level increases, these maximum-length strokes will start to sound separated because of the increased stick height needed to create the dynamic. The hands need to be sped up gradually, and the buzz strokes gradually shortened, to maintain the appropriate sustained roll sound.

The decision to switch into a triple stroke roll is simply a final extension of this gradual adjustment. As the roll becomes louder, and therefore faster, a point is reached at which the hands are moving fast enough to require only three strokes per hand. Experimenting with this transition will help students discover appropriate relationships between hand speed, stroke type, stroke length, and stroke volume. Mastery of these relationships allows students to create and maintain a sustained sound within a single passage or across a changing one (e.g., crescendo or accelerando).

Double Stroke Roll

Eliminating one more rebound from each hand creates a double stroke roll, which produces additional space between bounces and a more open sound. The double stroke roll is most often used in marching band, military music, and military-inspired concert pieces. The open nature of the rebounds creates the effect of a barrage of fast notes compared to the smoother sustain of a buzz roll. The technical challenges are mostly the same: creating consistent sound between the two notes on each hand, and creating consistent sound and rhythm across the two hands as they alternate doubles.

Isolating the hands again is helpful, and students should experiment right away with the difference between buzz, triple, and double strokes in succession on a single hand. Teacher and student can again model and copy, with the student focused on matching every detail of the three stroke types. Strive to make the difference between the three precise and consistent, while changing as little as possible in your technique for each switch. The main determining factors are the pressure placed on the stick from the middle finger of each hand, and the timing of the lift after the stick has struck the drum or pad. In the double stroke roll, the hands are moving in an even up-and-down relationship; they do not stay down for a majority of the time as with the buzz roll.

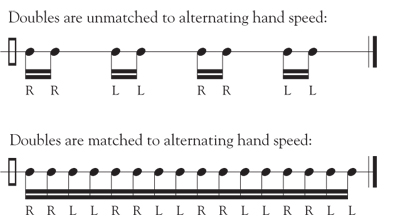

Precise timing is extremely important for developing a clean double stroke roll. Students must coordinate two intersecting tempos to accomplish this: the speed of each double (i.e., the space between the two notes) and the alternating speed of the hands. The examples below provide an illustration of doubles that are too fast (or hands that are too slow) and doubles that are just the right tempo to match the hand speed.

Matching these two tempos again requires experimentation. Perhaps the best way to find the right intersection is to begin deliberately with very slowly alternating hands, and gradually speed them up until the notes of the doubles become a constant stream. The key to success in this approach is not allowing the double spacing to change as the hands move faster.

Musical Decisions

Once students have developed the three roll types described above, they must learn to make wise decisions about how to incorporate them in musical situations. Four factors can contribute to these decisions: the sound of the roll desired, the length of the roll indicated, the tempo of the passage, and the dynamics of the passage. Teachers can make these decisions at first, but should ultimately help students develop the listening skills to make the decisions themselves.

Sound

Students must determine what kind of sound is desired from a given roll. Is it meant to be a dominating wall of sound or a skittering flourish of strokes? Smooth and full, or grainy and abrasive? Deep or superficial? Light or dark? Subtle or brilliant? These questions help to define the particular timbre of the roll without concern for additional musical parameters yet. Again, experimentation with all roll types will help to define which sounds align with which rolls.

Generally, a buzz roll will provide a more full, smooth, and deep sound, while a double stroke roll will provide a more grainy, articulate, and bright sound. Within each of these types, roll speed is very important. For example, a buzz roll will sound fuller as the hand speed increases, but will reach a point where the hand speed is so fast it sounds frantic. Conversely, gradually slowing down the buzz roll eventually leads to a sound of separation between the hands. Experimentation with this range of roll speed is crucial in developing decision-making for appropriate roll timbre.

Concert band and orchestra music tends to call for buzz rolls – and triple stroke rolls at louder dynamics – while marching band music usually employs double stroke rolls. Exceptions to this guideline occur when a piece of music in one ensemble setting is heavily influenced by the style of the other, such as a militaristic movement in an orchestral suite or an adaptation of a symphonic theme for marching band.

Finally, stick choice and striking area are important considerations in achieving appropriate roll sound. A thin pair of drumset sticks will produce a much different sound than a large pair of concert or marching snare drum sticks. One choice might be perfect for a jazz tune but not for a Sousa march. A soft, slow buzz roll may sound great near the rim of the drum but terrible in the center. Finding the right intersection of roll type, stick type, and striking area is a challenging but rewarding learning process.

Length

Rolls can be broadly categorized as either unmeasured or measured. Unmeasured rolls have indeterminate length, for example, at a fermata or the seemingly endless roll during The Star-Spangled Banner. Measured rolls have a specific duration in a given meter and tempo, for example, a half note of sustained sound in a fast allegro.

Unmeasured rolls generally require consistent sustain for extended periods of time. Students will need to develop physical stamina for these situations with appropriate attention to muscular health, as described earlier. They will also need to be able to mask the sound of the individual roll strokes by not allowing any particular pattern of hand motions to emerge conspicuously from the texture.

The most common example of this problem is a right- or left-hand dominated sound. In addition to improving their weak hand through daily tasks as described earlier, students can counteract this lopsided tendency during practice by starting the roll with the weak hand, accenting odd groupings of hand motions (e.g., three or five) deliberately while maintaining a long roll, and imagining odd groupings of hand motions (e.g., three or five) as they play the long roll evenly. The odd groupings help take both the mind and hands off of one-sided domination within the roll.

Measured rolls are short segments of roll fitted to a particular note length, tempo, and meter. When practicing these rolls, students should determine the roll base, that is, the underlying rhythm of the roll desired. Below is an example of a typical roll base that could be used to execute the notated quarter note rolls.

.jpg)

Students then simply layer one buzz, triple, or double onto each of the four notes of the roll base to produce the roll. Practicing roll and roll base in alternation can help students develop confidence and consistency in the rhythm of their hands when later playing the roll in context.

Tempo

With a firm grasp of the basic concept of roll base, students can begin to explore changing the roll base according to tempo. For example, the same quarter note roll in the example above played at MM=176 instead of MM=120 would likely require a different roll base, only three notes instead of four. Likewise, if that roll occurred at MM=92 it might require five or six notes in the roll base to maintain a full sound. Students need to be able to play various roll speeds within a given note to account for the tempo. They can practice this range of roll speeds in two ways: setting a constant pulse on a metronome and playing two, three, four, five, and six buzzes per beat incrementally; or practicing a set number of roll strokes at incrementally increasing tempos. In both cases, they are learning to find and to fit the appropriate number of roll strokes to a given note length and tempo. As students develop fluency with their range of roll speeds, they should also practice these exercises without the metronome, relying on their inner sense of pulse to maintain the beat as they shift with their hands.

Dynamics

Louder rolls typically require higher and faster roll strokes. Similar to tempo shifts, dynamic shifts require players to adjust their roll speed appropriately. Dynamics also require careful consideration of where to play on the head. In general, play soft rolls out towards the rim of the drum, making sure not to go so far that the sound of the snares becomes inconsistent or absent altogether. Play louder rolls close to the center of the drum but not right in the center. Playing an unmeasured roll constantly from loud to soft to loud will help players determine where to draw these boundaries on a particular drum. In addition, it will prepare them for crescendos and decrescendos in their music.

A crescendo roll requires gradual increase in hand speed and movement toward the middle of the drum, and a decrescendo roll requires the opposite. To help students develop the flexibility to change roll speed and playing area smoothly, practice giving them various conducting gestures for changes in dynamics and tempo. Their development in this skill will be very helpful to the sound of the ensemble.

In Conclusion

As instrumental directors, we spend lots of time helping our wind and string players develop full, characteristic tone with appropriate sustain, vibrato, and dynamic shading. In many situations, percussionists face different challenges, spending their practice time instead on rhythmic accuracy, coordination, and steady tempo. However, when it comes to the snare drum roll, the aim should be the same as for wind and string players. Investing the time and effort to help students develop the rolls described here, and choose when and how to incorporate them wisely, will improve their musicianship greatly.