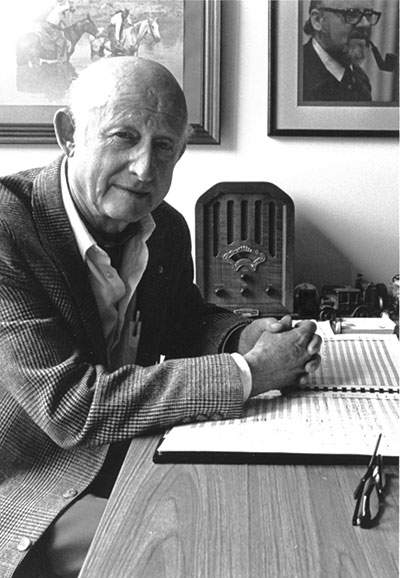

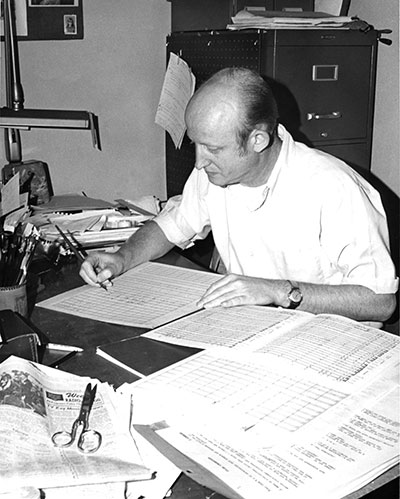

When this article was published in May 1990, W. Francis McBeth was professor of music, resident composer, and chairman of the theory-composition department at Ouachita University, Arkadelphia, Arkansas. He wrote extensively for band, orchestra, and chamber ensembles. He was a former conductor of the Arkansas Symphony in Little Rock and received formal education from Hardin-Simmons University, the University of Texas, and the Eastman School of Music.

How does a person learn a score? Volumes have been written on the subject, but how does one actually learn a score or a poem or a role in a play?

Seventeen years ago I became the conductor of the Arkansas Symphony in Little Rock and was faced with the challenge of learning scores of up to an hour in length. A conductor’s first employment with a professional orchestra is an overpowering experience in score study. This is a far different experience from university conducting, which covers only about a tenth of the literature a professional orchestra performs. An hour-long symphony is about a hundred times harder to learn than ten 10-minute works; it might seem that it should only be ten times harder, but this is not so for many reasons. It is a shock how quickly the repertoire learned in university years and in prior performing experiences is consumed.

After about 11/2 seasons, a full-time orchestra will go through a young conductor’s repertoire, and he will begin to leave duplicate scores in other rooms and spend all available time studying. I mention all this to explain why I had to start learning scores faster than ever before and what I learned from it.

The first step in score study is to memorize the score, and the second is to decipher the composer’s intent. The third step is to determine the conductor’s concept of what he expects to hear. The fourth step involves the technical approaches that we have all been taught, such as form and harmonic usage.

In using the word memory, I do not mean you should know the alto clarinet or viola note on beat 1 in measure 126 or the rehearsal letters by recall. Rather I mean knowing by memory the sequence of events of the work and being able to sing it from beginning to end.

When I make this statement in clinics, there is often one person who gets a bit upset. This is a natural reaction to something he thinks he cannot or does not need to do. I disagree that he cannot do it; but I agree that it is not always necessary. In fact, there are some scores that are not worth learning, not because of the quality of the scores but how they are used. If it is a training piece for a beginning band to learn various aspects of mechanical technique, and if you conduct four periods of this level a day, it’s not worth memorizing. However, I don’t know how one could keep a score out of memory by sheer osmosis.

Some conductors define score memory as knowing every note that each instrument has in any given measure, while others define memory as knowing the melody all the way through. I define score memory, or more accurately the memory that I use, as a memory knowledge of the order of occurrence in the composition.

If the word memory disturbs you, please note that the superb book by Elizabeth Green, The Modern Conductor, one of the few books on conducting that discusses score study in depth, does not use the heading of score study or score preparation. The chapter devoted to this subject is titled “Memorizing the Score.“ It speaks only of memorizing the score and gives the best information about how the memory works, and I recommend Chapter 17 to all of you.

Once you memorize the score, you know the order; once you know the composer’s intent, then you know the plot. Once you know the order of events and the plot, you are almost there.

Most articles on score study begin with the analysis of form. Trust me, you do not need to know the form first. What difference does it make if it is rondo concertant, sonata allegro, or stollen-stollen-abgesang? Form becomes obvious once you have memorized the work, and another major heresy on my part is that the form of a work has never aided me in learning it. It must help someone because almost everyone lists it as the first step in score study, but I cannot comprehend how it helps initial learning. The only way it could is for each separate form to be exactly alike in time (minutes passed) and occurrence. I do not mean that form is not important, because I know the form of every piece I conduct. I do mean that it is not a useful first tool for memory. In memorizing a poem, did you ever have to know the form first? Form is not a roadmap, and every sonata allegra is different. When a score is memorized, the form is obvious.

Perhaps those who recommend learning the form first are using the wrong term. To most musicians and all music academia, the word form pertains to a prescribed structure that results from the composers manner of presenting and developing the ideas in a work. Many use the term form when they actually mean the unfolding of a work (what I call the sequence of occurrence.) These are two completely different aspects. Orchestration has much more effect upon memory of occurrence than knowledge of the form.

The architectural study of form in college has never helped a composer learn form. Form is more complicated and important than superficial structure. The name form should be changed to glue. Form is what holds a piece together. One can have perfect architectural form and the piece can fall apart formally, but then that’s another discussion.

To return to my first step – memory. I don’t mean that you must conduct without a score, which can be used as an occasional reference during a concert, but you should have memorized the score to the point that if it falls off the stand you will be no worse off. At times I use a score for a concert when I have not used one in rehearsal, and always when a group is a bit shaky and may need extra help with a problem. Sometimes I put a paper clip in a score and open it only to a specific page I have trouble remembering.

Composers have a particular problem that most conductors do not, and I usually use a score when conducting my own music. I have heard so many comments, such as, “I don’t understand, you didn’t use a score on any piece except the one you wrote.“ The reason for this is that when you have composed music for 35 years, your brain can easily shift into another piece you have written. I don’t conduct from the score, but use it to remind myself now and then as to which piece I’m conducting.

Baroque music is the most difficult music to memorize because of its constant similarity. It’s like driving through a tunnel: the scenery does not change. Twentieth-century music is the easiest – the scenery is in neon.

If the first step in score study is memory, then how does one memorize a score? In the 1950s public education tried to get away from memorization and replace it with logic. Twenty years later, it dawned on educators that if you can’t remember it, you don’t know it. Knowledge is memory, wisdom is not.

Although I cannot explain memory, I know the process for achieving it is repetition, an ugly word in modern education: the repetition of singing through the score and playing through the score on a keyboard or a recording. A recording can be detrimental if you tend to take only the recording’s interpretation. Listening to Reiner with Strauss, Mitropoulos with Shostakovich, or Ansermet with Stravinsky can be a plus, but usually bandmasters will listen to a recording by the local Presbyterian junior college band, and this can be disastrous.

Singing while conducting or playing through a piece is far superior because you memorize faster when you participate instead of just listen. Listening is the slowest way to memorize and has interpretational pitfalls.

Try conducting through a score while singing it, silently, to yourself. You can silently sing melody, harmony, and percussion at the same time – try it. Not only is it possible, but there are never wrong notes or pitch problems in silent score singing. I have found that conducting while silently singing the score is the fastest method of score memory. While singing, you can stop and check the score at each mistake or error. This activity follows knowing the harmonies; it cannot precede it.

Learning the composer’s intent (plot) comes from understanding music and how composers speak through sound. I don’t know how it can be done without an understanding of composition, which should be the one required course for all music majors; yet only 2% study it.

I don’t know how one can fully understand anything that another does without ever having tried to do it. It does not mean that one should be good at it or successful at it, only that they have tried it. No one can appreciate a great bullfighter, a great aviator, a great sailor, or a great trumpet player if he has never tried it. Trying to understand music without ever having tried to create it makes it a longer road.

The composer’s intent is the most overlooked element among wind conductors and is the most important aspect in music. Without recreation of the composer’s intent, the exercise of performance is futile. Wilhelm Furtwangler said, “Everything purely mechanistic is a matter of training. But that understanding from which the word art derives has nothing whatever to do with training.“ This is a debatable statement but the older I become, the more I understand his point. I have asked a hundred conductors if rubato can be taught, and they all said yes, immediately. I wish I knew how to teach it. It is either right or wrong, and I can’t explain it to another. I can tell a student that it is too fast or too slow, neither of which would happen in the first place if he could feel it. How is feel taught?

To understand the composer’s intent, begin with the simplest and most often violated aspect, executing what is on the written page. Hundreds of times, I have stopped conducting a high school honor band and said, “When you get back to your schools, you should talk to your conductor about being a clinician. It’s great fun and wonderful travel and you don’t need to know anything. You only have to make the band members play what is printed on their parts.“ This is almost true. The first day of an all-state is primarily forcing the students to do what is printed on their parts. How many times have you been a participant in the following scene:

Conductor: “Timpanist, what does your part say?”

Timpanist: “What? Where?”

Conductor: “The note you just played, what is the volume marking?”

Timpanist: (Long pause) “Double f” (the reply is never fortissimo)

Conductor: “Why did you play mezzo-piano?”

Timpanist: (No response).

I know this sounds simplistic, but 80% of the time I conduct where the music has already been prepared, the volumes are not correct (99% with the timpani)

A composer speaks through many techniques but the one most used is volume variance, with dissonance running a close second. Volume variance covers much more than louds and softs and includes most articulation markings, and goes through style and down to phrase endings. However, let’s not get complicated and stay with louds and softs and the gradation between them. Incorrect volumes will kill the composer’s intent faster than anything other than an absurd tempo. Even slight tempo changes can harm it. I have a tape on my desk on which the slow tempos are ten counts too fast and the fast tempos are ten counts too slow; it destroys the entire effect. Why is slow music usually conducted too fast?

A few years ago I was in the audience when an excellent honor band performed a work of mine. The tempo was excellent and all the technical aspects were good, but the pianissimos were mezzo-piano and the fortissimos were mezzo-forte. I don’t know when I was ever more embarrassed to take a bow. The work is a dramatic work that I am fond of, and it sounded silly and made no sense. This isn’t a rare occurrence; it happens more often than not.

We could go into the other aspects of understanding the intent of the composer but the executions of what is printed is a major first step.

Step three is the conductor’s concept. In score study the conductor decides what he wants to hear and with what attitude and balance. Most young conductors are not sure what they want and accept what comes out as long as it is in tune – a disastrous approach. Young conductors worry about pitch and tempo; neither has anything to do with score study. Good pitch is assumed and the tempo is written on the score.

Before the downbeat I know exactly what I want to hear; if it is not what I expect I stop and force it into what I want. The first element that affects my ear and brain is always attitude; the second is balance. Young conductors stop for the wrong notes: I never do unless it happens twice. Notes mean nothing; attitude is everything. Don’t confuse attitude with composer’s intent. Attitude is the conductor’s intent, which he hopes is part of the composer’s intent, but he has no way of knowing for sure.

Step four of score study is learning technical aspects. Hundreds of classes and articles cover analysis of form, harmonic understanding, and rhythmic complexity. To understand controlled dissonance is to understand balance; to understand harmony (18th to 20th century) is to understand volume. These are most important. I do not make light of the technical aspects, which are essential but are easily accomplished.

I realize that I am in the minority on a final aspect of score study, that of marking the score. When I was young I marked much of the score because I was taught to do so. I found that my usual markings in an hour’s work caused me to spend more time reading markings than listening because the eye and ear do not work together. Once the eye goes to the page, the ears shut down 40%. It was a great revelation to me that if I had to mark the score, I didn’t know the score. I recently read an article on how to mark a score, but I feel that if you need to mark the score, you do not know the composition. We are not learning a score; we are learning a musical work.

Except for enlarging the numerals in multiple meter changes, one must know all the things that are usually marked. I realize this may be heresy, but I believe that a marked score is an unlearned score. To a lesser degree this is also true with the player’s individual parts.

After a recent concert I erased the markings from the parts and found three players that had circled, usually three or four times, the ff and the opening measure. If players need additional reminding that the work starts ff, then they either have no concept of the piece or their brains have been somewhere else during all of the learning process (rehearsal). I may be the only conductor who asks the ensemble not to mark their parts unless the marking is to correct an error, to change the printed material, or as logistics for the percussion. I want players to know how the piece goes; it is too late to read at the concert. I am not talking about bow markings, but I am tired of all those pencils clicking when I want everyone to remember and understand what I am saying.

I hope these thoughts are helpful to young conductors. Expanding your score study will build confidence and enhance the pleasure that comes from being in complete control. I leave you with this one important thought: you are not learning a score: you are learning a musical composition.