Contemporary band composers have expanded the sonic capabilities of the traditional concert band to such an extent that wind players are sometimes asked to create a variety of sounds that extend beyond their typical role as an instrumental musician. Audience members might hear band members sing, whistle, pop plastic grocery bags, or they may be engaged themselves as participants in the performance. Additionally, conductors are called upon to interpret a musical score that may look quite different than the traditional full band score. Although this is an exciting time in the evolution of band repertoire, these extended techniques can also pose some challenges.

During the mid to late 20th century, avant-garde composers began to explore a variety of new compositional techniques and new modes of expression. The way composers viewed the wind band was forever changed with works such as Karel Husa’s Music for Prague (1968) and Joseph Schwantner’s …and the mountains rising nowhere (1977). Since these monumental works, the quantity and sophistication of band music in the last several decades has grown exponentially, and extended composition techniques can be found in band music at all levels of the repertoire. Some of these include aleatory techniques, graphic notation, vocalizations (including singing, chanting, whispering, screaming, humming, and animal sounds), and such sonic effects as tapping, whistling, key clicks, blowing air through instrument, flutter tongue, and using mouthpieces only.

Vocalizations

The traditional role of the band instrumentals began to change dramatically when players were asked to use their voices in works like Husa’s Apotheosis of This Earth (1971), Schwantner’s ...and the mountains rising nowhere (1977), and Warren Benson’s Solitary Dancer (1970). Since these early works were premiered, the list of band works incorporating singing, speaking, chanting, and an endless variety of vocalizations has expanded tremendously.

Although the human voice might be mankind’s oldest mode of musical expression, some band directors seem to consider singing something they cannot or will not do. Some reluctance is understandable, as directors may feel singing in rehearsal wastes time, they lack the confidence in their own ability to sing, and they fear that students will respond negatively to singing. Although students (especially older ones) may initially appear unwilling to vocalize, this behavior may stem more from shyness or peer pressure than any real dislike for the activity itself. Although one might consider vocal sounds to have no business in a wind band, the added sonic timbre, when carefully woven into the wind texture, can provide a wonderful expressive quality.

Vocal parts that are to be performed by band instrumentalists appear in great variety, from simple humming to singing in multi-part vocal harmony. One common approach to this scoring is to have players sing a unison pitch, which is notated in concert pitch to be sung in any octave. A good example of this is in Andrew Boysen’s I Am, where the phrase “I am” is to be sung by all wind players.

A more complex vocalization example can be found in and the mountains rising nowhere where Joseph Schwan-tner creates a sixteen-voice “celestial choir” comprised of woodwind and brass players. These players begin by singing n on a unison B, and as the music progresses, each singer is eventually given complete rhythmic independence, resulting in a tone cluster on the notes B, C#, D, E, F#, G, and A. Conductor guidelines are provided and include an indication that when creating the sound of a distant ethereal choir there should be no vibrato.

A common technique used by composers is to begin with unison singing and expand to multi-part vocal harmony. In the example below, “All the Pretty Little Horses” from Three Folk Song Settings for Band by Andrew Boysen, the vocalization begins in unison in measure 49, and in measure 51, the parts divide into three-part harmony. In this example, each vocal part is assigned by instrument part, transposed in the key of the instrument. This scoring allows for instrumentalist to play along with the vocal part, which can be helpful when first learning the vocal pitches.

Of Sailors and Whales by Francis McBeth is a similar example, but in this case, the vocal parts are divided by women’s and men’s parts, not by instrument. The melody is first sung in unison octaves and is followed by a brief three and four part harmony section.

.jpg)

Introducing Band Members to Singing

If band members are not in the habit of singing in band, then the approach to vocalization should occur in a positive and unthreatening atmosphere. If the director demonstrates appropriate vocal modeling with comfort and security, students will, given time, follow the teacher’s lead and respond in kind. Ideally, players should start singing as part of their beginning band classes. Perhaps the easiest approach with beginning band students is to simply have them sing the exercises out of their band book before they play them. Advanced players should be able to sing scales, chords, and chorales, as well as their part within a musical composition. Generally, if singing is a regular part of rehearsal, band members will consider singing as normal as playing scales.

Directors who incorporate singing in rehearsals find that it is not a timewaster; it can improve the overall musicianship of the band members. Numerous studies have shown that singing can have a significant effect on instrumental performance and instruction with instrumentalists at various age levels. Students exposed to singing as a regular component of their instructional program tend to score higher on measures of music achievement, attitude, and developmental music aptitude. Structured singing furthers the development of a consistent sense of tonality and will result in better intonation at both the individual and the ensemble level. Many directors use singing exercises in daily warmups and rehearsals as a tool to improve tone production and intonation. Many of these educators tend to go by the philosophy that if you can sing it, you can play it. Suggestions from directors include having everyone sing together, incorporate solfège, sing familiar songs, and avoid pressuring anyone to sing alone.

Preparing Vocal Parts

When working with a band composition that includes singing, first examine the vocal writing to see if the parts are scored in concert pitch or transposed and placed in the instrumental parts. If the parts are assigned by male and female, determine if they are to be sung in unison or can be sung in octaves or in the range of the singer. In the case of multi-part vocalizations that are scored in the instrumental parts, determine if the parts are distributed to the appropriate voices. For example, if the tuba part is scored for lower vocal part and the player is a soprano, perhaps a reassignment of the part might be appropriate for that singer.

When initially learning the music, it is a good idea to play through the work a few times before learning the vocal parts. Play a recorded example of the piece so students can hear the context of the vocal parts. At this point, the director can introduce the vocal melody (if there is one) and have all the band members sing it as a rote song. To learn the specific vocal pitches, have an instrument play along with the vocal part while the band members first hum or sing on a neutral vowel. Non-transposing instruments, such as a flute or oboe for the upper vocal pitches and trombone for the lower pitches, work well for this activity. Having like vocal parts sit or stand together can also help at this stage. Once the vocal parts are learned, a refinement of the vocal elements may be necessary. There are a number of ways to do this:

• Create a brief vocal warm-up, perhaps on the same pitches being used in the piece.

• Remind band members to sing with proper breath and posture. Producing a hissing sound can be helpful in focusing the airstream.

• Practice matching the male and female voices while singing in unison.

• Unify vowel production. This can be introduced by starting with an mm sound and opening to an oo sound).

• Decide whether to use vibrato (no vibrato will produce a sound that is more pure and clear).

• Determine if men need to use falsetto. This is sometimes necessary for unison singing.

• Encourage each singer to blend his or her sound into the sound of the group.

• Balance vocalists with the instruments if playing. The singers may have to be urged to sing out, especially in the lower voices.

• Consider whether changing the seating arrangement can help with balance and getting the best sound out of the vocalists.

It is a good idea to solicit the help of a choral director or vocal teacher, especially if the vocal parts contain text. Many choral pedagogical references are available, a number of which are specifically written for band directors.

Vocal Sounds

The variety of non-singing vocalizations that appear in the contemporary wind band repertoire is extensive. These include imitating train sounds, mimicking jungle and animal sounds, shouting, chanting, speaking, screaming, and whispering and mumbling.

An early work that asked band members to vocalize was Husa’s Apotheosis of This Earth. In the third movement of the original version, Husa calls for rhythmic speech on the words “this beautiful earth.” The words are placed on non-pitched sextuplets with staggered entrances by the voices, interspersed throughout the movement. The first entrance for voices is in measure twelve with the upper woodwinds, saxophones, and several percussionists reciting one of the words. Due to this novel orchestration, and the hesitation by band members to vocalize, Husa later edited the vocal parts to be separate.

David Holsinger’s In the Spring at the Time When Kings Go Off to War is an example of a unique vocalization scored for female voices to sing wa repeatedly over a tone cluster of indiscriminate pitches and speeds. This electronic wa-wa effect begins in measure 10 and is to be sung as loudly as possible before fading to pianississimo. In this work, male and female voices have diverse assignments, including shouting and chanting.

It is often the case that wind composers will score several different kinds of effects in the same work. The example below, Many Paths by Ralph Hultgren, has the clarinets chant, sing, and clap in a three-measure span.

.jpg)

Sonic Effects and Techniques

Some of the most unique, non-vocal and non-playing sounds are scored for the wind band at all levels of the wind repertoire. Common techniques include blowing air through instrument, clapping, tapping on the stand, whistling, key clicks, flutter tongue, using mouthpieces only. Additional unique sounds that composers have notated for bands include playing the highest note possible (or a unique variation: “shrieking the highest note possible” by placing the teeth on the reed), blowing across a straight mute like an open bottle, playing tuned crystal water glasses, using flashlights, crinkling plastic or paper, and making sound with feet.

Aleatoric Techniques

Aleatoric music, in which elements of the composition, including dynamics, rhythm, pitch, and form, are determined by chance, has two main distinctions: aleatoric composition and indeterminate notation. In an aleatoric, chance, or pre-compositional music, the score is prepared in the traditional manner, but the process that the composer took to reach that point involves some element of chance. Chance compositions were widely explored by John Cage during the second half of the 20th century, and his experiments with the aleatoric processes and audience-determined sound production in the early 1950s were seen as an important milestone in the rejection of modernist unity and compositional control. Chance techniques may include the tossing of coins or dice, or by randomly arranging mathematical, textual, or sonic materials. Indeterminate notation, is where the composer establishes a means to allow each performance of a particular piece to be unique through some type of controlled improvisation. Although aleatoric notation can differ for each composition, commonalities do exist. Numerous examples of both distinctions can be found in all grades of the wind repertoire, allowing band students at any level to experiment with this musical technique.

One of the most used forms of notation is boxed or bracketed. In an improvisation box, certain musical elements are outlined in visual notation; these are improvised by the performer. There are a number of common examples of indeterminate notation. In H. Owen Reed’s For the Unfortunate, boxed notation comprises much of the composition.

Notated Pitches and Rhythm

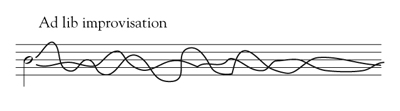

In the example below, The Glass Prison by Noah D. Taylor, specific pitches and rhythms are notated, but the performers play each box at a tempo of their own choice, repeating the phrase ad lib. Composers often use this term to indicate a somewhat non-measured improvisational section – either a controlled improvisation or spontaneously random.

.jpg)

In Old Churches, Michael Colgrass notates a rhythmical value, leaving the performer to determine the pitches.

.jpg)

He also indicates pitches while permitting the rhythm pattern to be at the performer’s discretion.

.jpg)

Other compositions may indicate specific pitches that can be played in any order with any rhythm, or they might use x-shaped notes to give pitch direction but not the exact pitch. Sometimes a starting pitch is indicated, followed by an ad lib section.

Additional notation markings used include accelerando (repeat beginning note)

.jpg)

and ritardando (repeat beginning note).

.jpg)

Some aleatoric sections are unmetered. In such cases, the events are typically guided the seconds timing markings as indicated on the score. The marking AFAP indicatess that the notes are to be played as fast as possible.

Introducing Aleatoric Music

There can be reluctance on the part of conductors and players to try out avant-garde compositions that ask band members to produce non-traditional sounds. New works that look and sound different than the standard wind band repertoire can be difficult to rehearse, perform, and present in a public performance. This hesitancy was noted when the first performance of Karel Husa’s Apotheosis of This Earth was postponed, one reason being the hesitancy of the players toward Husa’s use of spoken words and syllables.

One good resource to use when introducing aleatoric music is Sydney Hodkinson’s A Contemporary Primer for Band. It offers a series of preliminary exercises and short musical pieces that musicians to traditional, graphic, and aleatoric notation devices. Hodkinson’s sonic concept of time = space challenges musicians to navigate a new system of music notation in organized randomness. The pieces are scored using notated elements that permit chance performance determined by the performers. Later exercises studies allow for individual compositions in this style created by performers.

Graphic Notation

According to a study by Lewis (2010) all examples of graphic notation can fit into four broad categories: adaptations of traditional notation, grid notation, pictographic notation, and abstract notation. More loosely defined, graphic notation is the use of symbols and visual images that designate how the music is to be performed. Although this could include any notated music, graphic notation in wind band music refers to alterations of typical notation, and pictorial notations that would not be considered traditional notations.

Examples of graphic notation can be found as early as the fifteenth century in the works of Baude Cordier (1380-1440). His chansons Belle, Bonne, Sagein (below) and Tout par compas suy composes were defined as augenmusik (eye music), a technique that was later adapted in 1972 by George Crumb in Makrokosmos, and more recently in 1993 by Daniel Bukvich’s Hymn of St. Francis.

Although some contemporary composers continue to incorporate graphic notation, its use is both more rare and conservative than during its peak in the 1960s. Graphic notated scores pose a significant challenge to the performer, who must learn to decipher the composer’s intentions (which may or may not be easily understood) and attempt to play the music accurately. Band pieces may use a hybrid of traditional notation, pictographic notation, and abstract graphic notation. In Daniel Bukvich’s Symphony #1 the majority of the work is traditionally notated, with added aleatoric elements and vocalizations, all leading to the final movement, “Fire-Storm,” the score and parts for which feature, in part, a drawing of a burning city.

Introducing Graphic Notation

An excellent way to engage band members with graphic notation is to have players create group or individual graphic compositions. In Hodkinson’s A Contemporary Primer for Band, a compositional template is provided as a framework for composition. Michael Congrass, through his writings, workshops, and online references provides resources for band directors for creating a musical soundscape. Once basic parameters are established (the music moves from left to right, high sounds would be placed towards the top, and low sounds towards the bottom) band members create and perform their compositions. Creating graphic compositions is an excellent way for band musicians to be engaged in graphic notation and can motivate them to overcome any reluctance to explore this technique.

Closing Comments

New works that stretch the boundaries for the roles of musicians continue to be added to the wind repertoire. Although some of these techniques can be daunting to directors, detailed performance notes often appear in the score, and there are various teaching guides, articles, and texts that can assist wind conductors in the study of these new works. Exploring new kinds of music is an exciting opportunity for band musicians to experiment with an art form where there are no right and wrong answers.

A listing of band compositions of all grades that use these techniques.