Many student combos suffer from the lack of a creative presentation when performing. Too often they simply play through the melody, have everyone solo, then play through the melody again. With the next tune, they play the melody, have everyone solo, most often in the same order, and then play the melody again. I have heard entire performances that follow this pattern.

Many student combos suffer from the lack of a creative presentation when performing. Too often they simply play through the melody, have everyone solo, then play through the melody again. With the next tune, they play the melody, have everyone solo, most often in the same order, and then play the melody again. I have heard entire performances that follow this pattern.

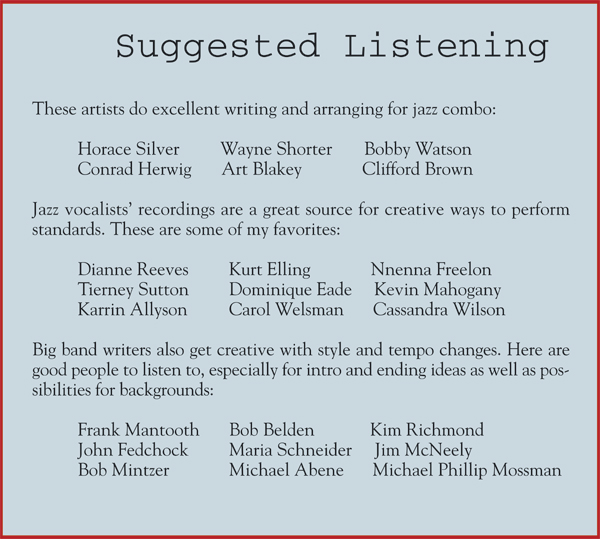

This approach works well when used by jazz greats, but for many students it puts too much pressure on their improvisation skills to keep listeners’ interest. Limiting the number of soloists and changing the order of soloists can help a little, but there are a number of ways to make combo performances more exciting while teaching students some basic jazz arranging at the same time. Recordings by Horace Silver or Art Blakey give a good idea of how much some simple arranging can enhance the sound of a group.

Most combos play out of fake books, which are a great resource, but these often provide only basic melodies and simple chord progressions. Although it could be beneficial to have more arranging provided, I prefer the blank canvas such books provide; it leaves plenty of room to create interesting arrangements that can custom fit any group. The tune “Dearly Beloved” from The Real Book, Volume I (Hal Leonard) is an excellent example of a chart that lends itself well to some arranging.

Enhancing the Melody

There are a couple of simple techniques that can be used to make a melody feel like it swings more.

Anticipation

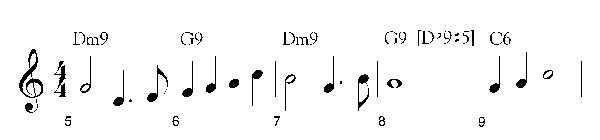

Often certain downbeat melody notes can be moved ahead by half a beat, giving the phrase a much more swinging sound. This is usually most effective when used at the ends of melodic segments. The pitches do not change at all.

.jpg)

Syncopation

Syncopation is simply taking consecutive downbeat notes and moving them ahead by half a beat to create more upbeats. Again, pitches have not changed from the original.

Non-Harmonic Tones

Adding simple non-harmonic tones to a melody will generate more energy by creating more movement. Passing tones, neighboring tones, escape tones, and appoggiaturas can all work. In this example the melody is slightly changed, but the original pitches are all still there. In measure 6, the original melody consists of four quarter notes: F, G, A, and C. We can add a passing tone B between beats 3 and 4 and then anticipate the B on beat 1 of the next measure by moving that to the upbeat of beat 4. This creates a nice diatonic eighth-note run that swings much better and generates more energy with the moving line.

Enhancing the Harmony.jpg)

A good way to approach reharmonization is to analyze the relationship between the bass note or root of the chord and the melody. By substituting for certain chords a much more interesting relationship between the bass and melody can be created. Do not try to change every chord in the tune, and avoid changing chords that are unique to a tune or used at the beginning or ending of phrases.

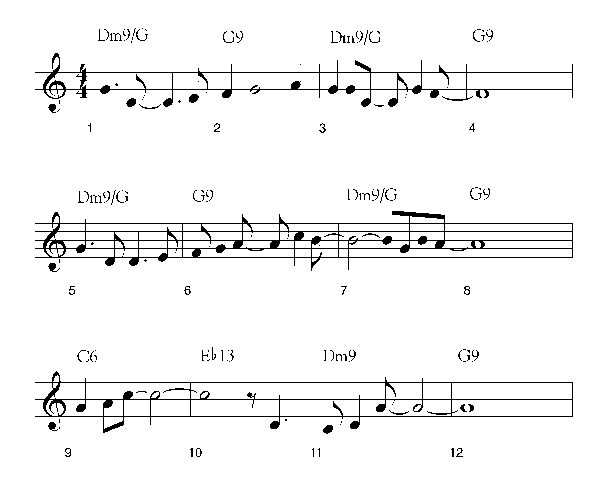

Simple Chord Substitutions

Most tunes are built with major, minor, and dominant chords. The simplest substitute for a major or minor chord is to move the bass note a diatonic third away in either direction. Each of the new chords will share multiple notes with the original chord but has a different sound because of the root movement. With this technique, starting from a major chord will produce minor chords, and starting from a minor chord will create major chords.

When substituting chords it is important to look at the relationship between the new chord and the chords surrounding it. In the example below, the C6 chord in measure 10 could be changed to either an Am7 or an Em7. The C in the melody will clash with the fifth of the Em7 chord, eliminating that option. Am7 works beautifully with the melody, and also produces a logical progression of C6-Am7-Dm9-G9. If the chord progression sounds forced, a substitution should be avoided.

In addition, the CMaj9 chord in measures 13-14 can be changed. The G, B, and D in measure 13 fit perfectly into Em7, and the next measure could work with an A7 chord. This produces an interesting Em7-A7-Ebm9-Ab9-Dm9-G9 progression.

A simple solution for dominant chords is to substitute the chord a tri-tone away. Two dominant chords with roots a tri-tone away share (enharmonically) the same third and seventh, and there are many instances in which substituting at the tri-tone will create an extremely colorful relationship between the chord and the melody. In this example, tri-tone substitution produces an interesting D-D flat-C run in the bass line.

Secondary Dominants

Secondary dominants are frequently used in big band writing. At any time a chord can be considered a temporary tonic, in which case a dominant can go in front of it. Although this technique is easy to abuse, it adds quite a bit of color and energy. In the example below, the chord in measure 10 can be changed to an A7#9 leading to the Dm9, or to really make things interesting, use tri-tone substitution of the secondary dominant and add an E-flat 13 chord instead.

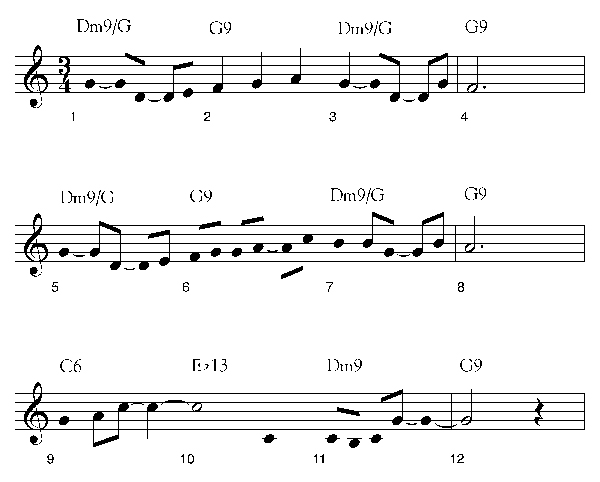

Pedal Point Bass

A favorite technique of mine is the use of bass pedal points. Many jazz standards are built using IIm7-V7 progressions. Placing the IIm7 chord over the same root as the V7 chord creates a bass pedal point that slows down the harmonic rhythm. A pedal point also opens the arranging possibilities to adding a rhythmic or even melodic ostinato on the bottom of the arrangement.

The example above could also make an excellent introduction.

Have just piano and bass play the pattern for four measures, then repeat it, building by adding drums lightly catching the piano and bass rhythms and guitar. If the combo has a trombone or bari sax, this player can double the bass line for the second four measures of the intro. In this chart, the ostinato can continue through the first eight bars of the tune, then the bassist and drummer can switch to a walking line and swing style.

Changing Tempo, Meter, or Style

A simple way to change up a tune is to change the tempo. It is especially effective to take a ballad and push the tempo up to medium or even fast swing. Arranger Frank Mantooth was a master of this.

Another option is to change a tune from 3/4 to 4/4. All sorts of ideas will stem from condensing the original melody to fit the new time signature. Here is the first half of “Dearly Beloved” played as a waltz.

Changing the style of a tune can also liven things up. Converting a common swing tune to something in a Latin, rock, or funk style will naturally inspire some simple arranging ideas for the melody. “Dearly Beloved” as a bossa nova might start this way.

Orchestration

Using various instrument combinations within a combo may be the easiest way to add interest. A group with three horns has seven different options for who plays – and that is without even considering the rhythm section. When changing combinations, think in terms of longer phrases. Changing more frequently than every eight or 16 bars will make the tune sound fragmented.

Changing or adding instruments should help the tune build. Think low to high and few to many. Starting with bari sax and trombone, then progressing to alto sax and trumpet will naturally build the tune. A tune will also build if you start the first phrase with just one or two horns and end with all of them playing the last phrase.

During Solos.jpg)

Although a tune itself can be quite heavily arranged, simple is better during solos. I frequently revert back to straight-ahead swing and near original chord changes. It is important to use the rhythm section to build each solo with volume and activity, then drop in volume and build again with subsequent solos. This adds a lot of interest to the performance and also encourages young soloists to build their solos. The drummer can change the texture by alternating ride cymbals with each soloist; another way to add variety is to have drums, bass, or piano drop out at the beginning of a new solo and come back in halfway through.

The number of solos should be limited, and the order of solos should be changed for each tune. One idea is to have piano or guitar solo before the melody is played for the first time.

The End Result

The instructions for an arranged version of “Dearly Beloved” might look something like this:

• Intro: Eight measures of pedal point ostinato. Start with bass and piano; add bari sax and drums in bar 5.

• Melody: Trombone and bari sax play first 8 bars over the ostinato, bari and alto sax play the next 8 in a straight-ahead swing style. Trombone and trumpet play the third 8 bars (over ostinato), and all play the last 8 together (swing).

• Solo 1: Alto sax (guitar comp, straight-ahead swing).

• Solo 2: Guitar (piano comp, straight-ahead swing).

• Solo 3: Drums solo over the ostinato as a vamp.

• Melody: All play, with alternating ostinato and swing sections.

• End: Same as intro, but drums and bari sax play the first four bars, then drop out.