Czech-born composer Karel Husa (1921-2016) won a Pulitzer Prize in 1969 for his String Quartet No. 3 and a Grawemeyer Award for his Concerto for Cello and Orchestra in 1993. Although these pieces garnered prestigious prizes for Husa, he is best known for his wind band/ensemble masterpiece, Music for Prague, 1968, which has received over 10,000 documented performances. In 1969, Husa created an orchestral version of the piece that has been performed many times by the world’s leading symphonic orchestras. (Conductor George Solti was a great champion of the work).

A commission he had just received from conductor Kenneth Snapp and the Ithaca College Concert Band provided him with the perfect vehicle to do so. During the next month and a half, using serial, avant garde and traditional compositional techniques, Husa composed a powerful, dramatic four movement, 22-minute long overt response to the Soviet invasion of Prague and his homeland.

Music for Prague, 1968 abounds with symbolism. A 15th-century Hussite anthem, Ye Warriors of God, symbolizes resistance and hope, bell sounds reflect Prague’s “hundred spires,” trombones imitate air raid sirens, oboes play Morse code-like passages, and a piccolo sounds bird calls, a symbol of freedom, something the people of Prague have only experienced briefly during its thousand years of existence.

Over the years many articles and dissertations have been written on the work’s background, structure, interpretation and performance challenges. However, no one (to my knowledge) has investigated what transpired in the rehearsals that led up to its premiere performances. Apparently neither Husa nor Snapp left notes, documentation of what transpired during the rehearsals or at its premieres. I decided to contact former students who played in the Ithaca College Concert Band at the time to enquire about their remembrances of what occurred.

Music for Prague, 1968 was a radically different piece – unlike any work played by wind bands at the time. For many players in the band, it was their first encounter with real contemporary music with elements that included new notational symbols, serial composition, technical demands, quarter-tones, and improvisation.

Rehearsals

The Ithaca College Concert Band began rehearsing Music for Prague, 1968 immediately after performing their first concert of the school year on October 25, 1968. Concertmaster clarinetist Robert Hayden, stated that “the band was not able to ‘read down’ Music for Prague, 1968 from beginning to end without stopping. [We just tried] to get through it. It took several rehearsals [before we got] a feel of how rich and intense the piece was.”

Band members recalled that Husa spent a considerable amount of time working with both the full and individual sections of the band. He also met and discussed various details of the piece with individual players.

Frank Phillips, a clarinetist in the band, recalled that “we were in many ways a lab band for him. He would come to rehearsal, pass out parts [which were] scratched out in pencil [and then] rehearse a specific section. I recall one rehearsal when Mr. Husa experimented with the trumpets, having [the players] try different combinations of mutes, one [using a] Harmon [mute] with [the] plunger in; another with [the] plunger out, etc. He would write notes [in] his score [and then] leave [and] return another day. My participation [was] exciting and inspiring. The challenge, [in addition to playing] technically correct, was [to grow in] understanding the emotional intent of the piece. This was a very new experience for me, a naive sophomore clarinet player who had no previous exposure to contemporary literature.”

Trumpet player Donald Riale also recalled the composer’s experimentation with trumpet mutes. “He had me bring all my mutes to his office and demonstrate various sounds so he could select what he wanted for the trumpets. He [had written in] some impossible mute changes, so I got him to modify those!” Riale added, “I drilled my section on the piece so we were very tight and I’m very proud of the results we got.”

Bass trombone player Donald Robertson stated that Husa “worked with each instrument to explain their role in the music. When he came to the trombones, my instrument, one of the details he [clarified for] us was that the glissandos [represented] diving airplanes and the bombing of Prague. As I recall, we worked very hard to get this effect and not play the notes in a typical glissando manner.”

Principal percussionist Gary Rockwell spent a good deal of time with Husa “exploring the complexity of the percussion parts, the fabric of the sounds he wrote as well as the re-writes to [achieve] his intent. While [preparing] his work [Husa] consulted with the percussion [players], and the percussion teacher at the time, Jack Moore. [He] spent [a lot of] time with us rehearsing and balancing the complex parts and overall textures he sought [in the percussion movement].”

“I was the percussion section leader and [played] the solo snare drum part which moved me every time we played the music, knowing what [Husa wanted to express.] His thorough approach and curiosity were always present.

John Farrell, another percussionists who was also a composition student of Husa, recalled that “during our weekly sessions, [when] he was composing the piece, Husa discussed various aspects of the multiple percussion instruments [with me. I played the vibraphone part.] He showed me movement 3 and asked what I thought. I was flattered that he asked. I loved the piece although I had no sense of why it was so important to him.”

Bass Clarinetist Ardis Leyburn Ketterer stated that Husa “was concerned [whether what] he had written for [the] instruments [was] in their proper ranges. Husa [said he] was more familiar with strings. A few changes [had] to be made in the manuscript parts. [Husa] was so easy to work with and appreciative of our efforts.”

Robert Albretsen, a tuba player in the band. wrote that “the ink was still wet [on the parts at the] first rehearsal. Husa often attended rehearsals encouraging our efforts and fine tuning the score. The turning point in our [preparation] came the day he [communicated] his love for Prague and how the music expressed the indomitable spirit of his people to be once again free. This changed us from a group of musicians trying to play a piece of music to a single organism expressing an idea.”

First clarinetist Tony Pietricola wrote that he and the other clarinetists “spent hours together in the practice room hashing out the wild interval skips and rhythms. I don’t think we really got it right until we played it in Washington.”

Based upon the recollections of players, it appears that the composition of Music for Prague, 1968 was significantly influenced by what transpired in rehearsals between Husa and the band and the one-on-one discussions he had with individual members of the ensemble.

Premiere Performances

Music for Prague, 1968 received its official premiere performance by the Ithaca College Concert Band, Kenneth Snapp, conductor, on January 31, 1969, at the Eastern Division Conference of the Music Educators National Conference (MENC) in Washington, DC. Its unofficial premiere took place a month earlier in Ithaca, New York on December 13, 1968, at a concert performed by the same band. Ithaca Journal music critic, George Clarkson, wrote the following about Husa’s new work:

“The major work of the evening was commissioned by the Concert Band [and] composed by Karel Husa. Very interesting techniques …as well as [orchestration]….The [Hussite] song…as woven by Karel Husa spoke of all the passion of the Czechs and their deep longing for freedom. The song also was a mark of unity appearing at the outset, though never in its entirety, and then coming back with stirring strength in the final Chorale. Even in the tragic “Aria” section there was a strange majesty. The color of Prague with its ‘hundreds of towers’ came through with…persistent ringing…. One left…with a strong feeling that music as great as this should not be written about – one should only listen and be deeply moved.” (“Music Review: I.C. Concert Band, Ford Hall.” Ithaca Journal, December 14, 1968, p. 8)

En route to Washington DC (for the MENC concert), the Ithaca College Concert Band stopped and performed a concert at Rahway High School in New Jersey. (Rahway is the home of Rahway State Prison where the Scared Straight TV series was filmed.) In recalling this concert, Robert Albretsen remembered that he had wondered how the students would react to Music for Prague? “Their response was overwhelming! Music for Prague transcends all barriers.”

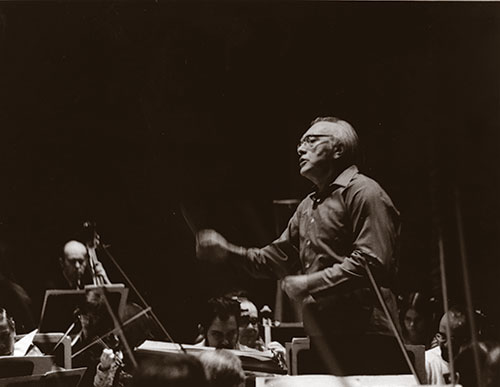

Washington, DC Premiere Performance

There was much excitement as the band prepared to go on stage for the MENC Conference concert. Karel Husa was there, and everyone wanted to perform the piece well for him. George Proios recalled that when he was setting up percussion instruments and equipment for the performance, he saw other people setting up some electronic equipment. When he asked them what they were doing and why they were there, they said they were from Radio Free Europe and were arranging electronic equipment to broadcast the performance of Music for Prague, 1968 “to people behind the iron curtain.” This brought home to George the significance of what they were about to do.

Dr. Snapp and everyone in the band had great concern about the health of bass saxophonist Garrett Lai-Hipp. Robert Albretsen recalled that Garrett had been “very sick with the flu. He [was] on the verge of passing out as concert time approached. [However, he was able to] summon up enough strength to play.” Shortly before the band went on stage, the piccolo player fainted. Again, she recovered and was able to play the concert.

The audience response to the performance was at first “complete silence and then a roar of applause, as the whole audience rose to its feet for a standing ovation.” Ardis Leyburn Ketterer noted that the audience’s response was “overwhelming!” She said she “had chills” Karen Dembow Erler remembered feeling like “something ground-breaking had occurred, [something] bigger than ourselves.”

In an interview I did with Karel Husa for The Instrumentalist in 1990, Husa spoke about his presence in the audience at the premiere of Music for Prague, 1968.

“During the program I ended up sitting with people who didn’t know who I was. It was amazing that at the end of the piece, immediately the people around me stood up; I didn’t stand up immediately, as I was astonished by the reception. Kenneth Snapp, the conductor, signaled me to come to the stage. It was an emotional time for me; I had never before experienced anything so moving. It is satisfying to know that the belief I had in 1968 was not in vain. Life has confirmed that freedom is the supreme thing in man’s existence and it’s worth fighting for.” (Frank Battisti. “Karel Husa – Keeping Ties with Tradition,” The Instrumentalist Vol 44, No. 12, July 1990, p. 42)

Following the concert Husa joined Dr. Snapp and some of the band members to celebrate the occasion. Robert Albretsen recalled that “Husa was [very] happy but still very humble, praising the performers – very much in character, as always.” He added, “In the early 1990s [when] I was driving to work and listening to NPR, they played a recording of Music for Prague. At its conclusion it was announced that Husa was returning to Prague to conduct the piece with the Prague Symphony Orchestra. Tears of joy flowed so hard that I had to pull off the road.”

Don Riale said band members felt “it was a major work and were deeply [affected] by [it]. [It took a while before we realized that it was one of] the greatest works ever written for band.

John von Rhein, music critic for the Chicago Tribune, described “Music for Prague as being “powerful, dramatic and disturbing: even if one listens to it as pure music, it is impossible to remain unaffected by it.”

Karel Husa, The Human Being

Everyone in the Ithaca College Concert Band respected and admired Karel Husa. Tony Pietricola described him as being “a most kind and gentle human being.” He recalled meeting Husa years later at a MENC Conference in Boston following a performance of Music for Prague, 1968 by the Duquesne Concert Band which had been guest conducted by Husa who was now in his 80s. “I just had to go up to him and tell him I had played in the premiere performance of his piece. He looked at me and said, “Ah, yes, Tony Pietricola, I remember you.” I was not wearing my name badge and had not yet introduced myself! Amazing!

For Gary Rockwell, “Karel Husa was an inspirational human being.” Fellow percussionist John Farrell thought he was “a vibrant and gentle man, who always had a smile on his face. He would wax whimsically, ‘wouldn’t it be fun to have a 40-piece orchestra to tour around and play all [your] own compositions.’ Fifty years later I can still hear him saying – ‘Isn’t that curious?’ [A comment that is] so much more intellectually inviting than ‘Look at this’. He was a remarkable human being!”

Postscript

I recall a conversation I had with Karel Husa in the early 1960s. He told me that he hoped to write a piece about Prague that conveyed the beauty and spirit of the city and its people. However, the tragic events that took place in 1968 motivated him to compose a very different kind of piece about the city – a masterpiece that illuminates and expresses the defiant and courageous spirit of Prague and his fellow Czech countrymen/women.