Ensemble rehearsal time is a precious commodity that cannot be wasted, and diminishing financial support for many instrumental programs also prohibits directors from ordering new music for their ensemble, therefore limiting the number of works the ensemble may have available to sightread throughout the year. Fortunately, there are creative ways for directors to recycle some of their print materials while only using a very small fraction of rehearsal time.

Sightreading Priorities

To develop a culture of sightreading, establish a hierarchy that promotes ensemble success. Although rhythm is one of the most common problems during sightreading, it is not the first component I discuss when offering a new work to my ensemble. I address these elements in the following order:

1. Road maps

2. Time signature

3. Rhythm

4. Key signature

5. Miscellaneous musical attributes, such as dynamics, articulations, and style

Addressing the elements in this order has provided my ensembles a firm understanding of what we consider important when performing music for the first time.

Getting Started

For developing ensembles, sightreading a homogeneous passage may be best initially. While there are a number of resources available, one affordable source is the Raymond C. Fussell Exercises for Ensemble Drill, which contains a section with 40 different eight-measure melodies that increase in difficulty. When I taught high school band, each day’s agenda usually included an exercise from this book. In the beginning, we kept things simple, reading one exercise in its original form. This exercise is not too demanding, making it a good choice to build students’ confidence quickly.

Getting Creative

In a subsequent rehearsal, directors can get creative with the same exercise. One way to recycle the first excerpt is for the director to ask the students to read the line backwards, so it sounds like this:

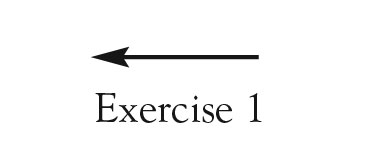

I have developed a shorthand for indicating how I want students to read through a melody. In this case, I would list it on the board as:

When reading this way, it is important to establish the rule that any dotted rhythm must keep the dot with the original note. When reading backwards, the rhythms in measures four, five, and seven will include an eighth note followed by a dotted quarter note. It is true that there will likely never be a reason for a musician to read their music from right to left, but the exercise helps students think critically about music reading and improves their ability in that area. Do not rewrite these exercises backwards, unless in is the first attempt and students struggle to understand how the music should be played.

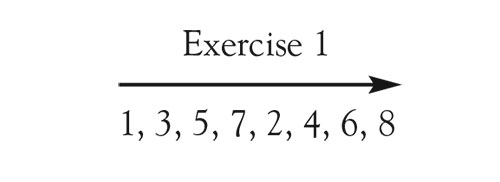

Once the students are comfortable with reading the original material and asked to alter it for an immediate performance, the creativity of the director can challenge the students further. One example is transposing the exercise up a half step so it sounds like this:

This exercise is listed as:

The ability to transpose at sight is something that many brass players (especially those who play horn or trumpet) might need in orchestral literature or older band works. This exercise also challenges students by having them play in keys that they may ordinarily not be asked to perform.

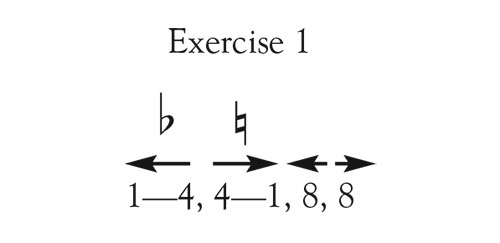

Another good variant is to have students play odd-numbered measures followed by even-numbered measures.

This exercise might improve eye movement, which in turn can make navigating complicated road maps easier. My shorthand for this would be:

Even more creative combinations can eventually be tried. In the excerpt below, students are being asked to perform measures one through four in that order, with each measure read backwards and down one-half step. Immediately afterward, the students are asked to perform measures four through one at the written pitch, with each measure read from left to right. The final two measures require students to perform measure eight two times, with the first time read from right to left and the second time from left to right, both at the written pitch.

.jpg)

Admittedly, when I used to request such difficult alterations from my high school students, the first performance was often met with less-than-desirable results. When that occurred, we would regroup and sing through the passage while students fingered the notes. We would then perform the excerpt a second time. In most cases, the performance improved with variable results.

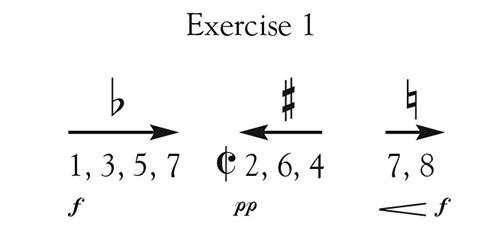

A final example includes several elements in the miscellaneous category from my sightreading hierarchy.

In this example, the students are to perform measures one, three, five, and seven, read from left to right, transposed down a half step, and played forte. This is followed by measures two, then six, then four, all played in cut time, read from right to left, transposed up a half step, and played pianissimo. The final two measures, seven and eight, should each be read from left to right and played at the written pitch with an added crescendo and legato.

This is a highly complex request that might require several attempts before it is performed near reasonable expectations. However, once students can follow and play through such a road map, sightreading music normally will seem simple by comparison.

Challenge the Band Director

On Fridays during the fall semester, my high school band was expected to perform at every football game, including the away games. To help save students’ chops during that day’s rehearsal, we had a Challenge the Band Director session. Up to three students each Friday could create an altered Fussell exercise to perform. After their performance, I received 30 seconds to prepare the excerpt exactly as offered by the student, with the same rules that we would need to follow at state assessment. The most important rule was that I could not play my instrument during the preparation time. After 30 seconds, one of my students would call time, and then I had to perform the excerpt on my trombone.

One Friday, a sophomore trumpet player named Jonathan said, “I am going to make your life easy today. I am going to perform an exercise completely backwards and down a half step.” With such a simple alteration, I assumed my perfect record of winning the challenges would continue.

I began to worry when I saw that the exercise’s original key was Db. My first thought was to think about transposing each note as I would advise my students, however, panic quickly ensued, and I resorted to extending my slide position by one for each note. By the time I settled on which procedure I would use, Jonathan completed his performance (exceptionally well, I might add) and my preparation time had elapsed before I had gotten through three measures.

I began my performance by making a mistake in the first measure. I then immediately put my instrument down while the students ecstatically celebrated the end of my undefeated streak. As the cheers died down, Jonathan smiled and asked me if I wanted to know his secret to success. With an angry band director stare, I went to the back of the ensemble to check his book, as one of the rules was that you could not write out any alterations. Jonathan’s book was clean, as were the books of all the students around him. I begrudgingly asked Jonathan to share his secret, and he held up his trumpet to show me that he had extended every slide to its maximum, which offered the transposition assistance needed. I was thoroughly impressed with his awareness and creativity and offered Jonathan my public congratulations but then proclaimed that altering an instrument to assist with transposition was no longer allowed.

Conclusion

When my students sightread traditional music that was appropriate to their ability level, I noticed that they did so with greater ease. An occasional repeat or simplified road map with a dal segno or a coda was no longer a challenge. Rhythms and pitches were also more likely to be correct. With so much improvement in these fundamentals, we were able to expand our preparations into the more musical aspects of performance. The time invested in this activity appeared to improve my ensemble’s sightreading ability, which offered everyone a better performance experience.