Most conductors realize that attainment of the right tempo is one of the most important aspects of an artistic musical interpretation. Ironically, however, as all seasoned musicians know, there is often great disparity among the choices that conductors make as they seek just the right tempo for any given composition. Leonard Bernstein judged the issue of correct tempo accordingly: “No two conductors agree, and if you were to listen to six conductors, you are likely to hear six different tempi. Yet each conductor is convinced that his tempo is the only true one.”

Because composers often indicate tempo with precise metronome markings, it might seem reasonable to expect that performances of a given selection would be uniform with respect to tempo. However, this is not the case. When listening to different versions of the same compositions recorded by professional ensembles under different leading conductors, it readily becomes apparent that the selection is played at a different speed on each recording. Even the tempo directed by the same conductor for the same composition may vary with each performance.

As conductors, it may sometimes seem that we are chasing a will-o-the-wisp when we seek the correct tempo. A conductor may feel slightly unsure what to do when opening the score and seeing con brio quarter note = 140 in the upper left margin. Unfortunately, in formal conducting study, the most attention is usually devoted to subjects like baton technique and repertoire, whereas the critical matter of selecting and maintaining the correct tempo may be neglected and left to chance.

A brief overview of the history of the metronome and tempo markings proves to be both helpful and interesting. Precise establishment of tempo through metronome markings became possible after Johann Maelzel (1772-1838) obtained a patent for the metronome. Ludwig Van Beethoven was the first major composer to use metronome markings, and he indicated tempo markings for his first eight symphonies in a publication in 1817.

A few side stories are of interest here. Beethoven was so taken with the possibilities of the metronome that he became very fond of Maelzel, who invented more than just metronomes. Maelzel also devised hearing aids and different kinds of mechanical apparatus for popular entertainment, including a mechanical chess player (which was ultimately revealed to be a hoax, as it simply concealed an actual person who made the cunning chess moves). Beethoven regarded Maelzel so highly that the great composer wrote his “Battle Symphony” for Maelzel in exchange for some hearing devices. Although the hearing devices did little to help Beethoven, the Battle Symphony enjoyed great success on tour, and Beethoven later had to fight legal battles to retain his rights to the music.

Unfortunately, the metronome markings that Beethoven endorsed around this time are now recognized as misleading. As Emil Kahn has pointed out, “the finales of the Eroica and Seventh Symphonies are marked so fast that if performed according to Beethoven’s indications, they would be unduly rushed. The opening of the 9th Symphony would result in chaos.”

The misrepresentation of tempo through metronome markings is not singular to Beethoven. Indeed, this is a common problem that has affected many composers through the years. Composer-conductor Francis McBeth noted this problem when he observed: “Composers are notorious for writing in wrong metronome markings. By that I mean the marked tempo may not be the best.” As an example of this, McBeth noted the problematic markings for the Beethoven symphonies. McBeth also remarked that his experience as both a conductor and a composer gave him special insight into how this problem arises. Based on in his experience in the worlds of composing and conducting, he observed: “A tempo at one’s writing desk is seldom the same on the podium. Before I publish a work I usually conduct it in concert twenty or thirty times before finalizing the tempi, and I end up changing sixty percent of them.” Even so, the amount of change made is usually slight. McBeth cautions: “Before changing a published tempo make sure you are right. Very few changes will exceed eight counts one way or the other.”

Another reason for inaccurate metronome indications is that sometimes the music editor may have added or changed the metronome markings, perhaps without the composer’s approval. This was especially common in the Romantic Period, when the use of the markings was just emerging.

Because of these problems with metronome markings, conductors should take the view that, rather than settling and firmly establishing tempo, the metronome markings in the score merely provide suggestions. The conductor should bring additional knowledge to the score, including knowledge of the historical period of the music, familiarity with traditional interpretations, understanding of the occasion for the performance, and an honest evaluation of the capabilities of the performers.

Herein lies a paradox regarding use of the metronome. While it may be agreed that metronome markings only offer suggestions, the conductor must also have an accurate sense of the different time indications. The metro-nome is a great study aid to help conductors and musicians establish a personal sense of different tempi. Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini made full use of the metronome well into his eighties to check the accuracy of his tempos. Toscanini’s familiar statement – “It is easy to play a piacere, the thing is to play a tempo” – underscores the importance of using the metronome.

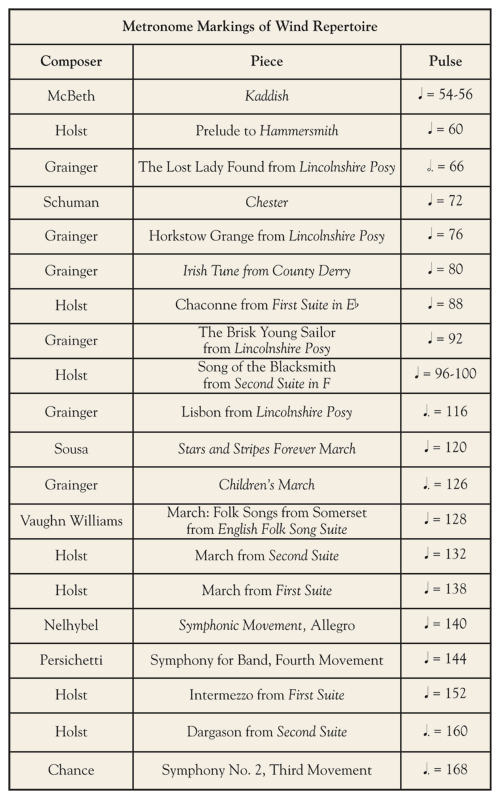

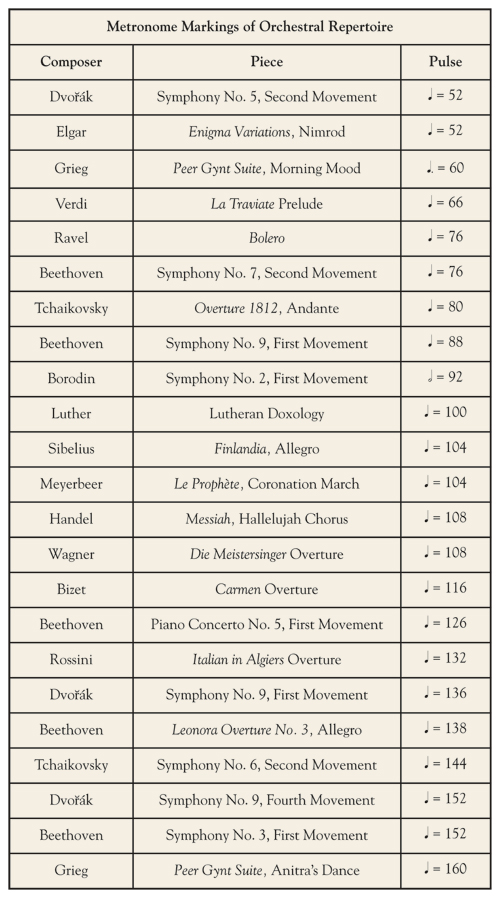

I have found that memorizing the tempi from familiar band and orchestra repertoire, as shown in the tables below, will greatly aid in setting a tempo for a new piece of music with indicated metronome markings.

I would caution conductors to remember that these tempo markings of familiar pieces should serve only as a reference point to unfamiliar music, and should be used only as a starting point to interpreting the music. Toscanini simplistically recognized that there are three different stages of tempo: the first is the tempo felt upon first reading the music; the second is the tempo used at rehearsals; and the third tempo is established at the public performance.

Significantly, conductors should realize that tempo provides only the musical frame of a composition. For music to have verisimilitude it cannot be bound to metronomic rigidity. The noted flute virtuoso William Kincaid gave the following sage advice about use of the metronome:

“Playing metronomically correct with scrupulous observance of dynamics is something that too often passes for artistry, but because of its mechanical and honest nature it can amount to no more than a student sort of playing. Music demands an impressionable, plastic sense in regard to rhythm, rather than a correct, static concept. Play with the melodic line, making delicate gradations and fluctuations in tone and rhythm, yet only within the fundamental pulse.

“Do all phrasing, all nuances and liberties within the measure so that the unit of rhythm, the frame, is not disturbed. The discipline of the measure remains intact while the freedom is taken within this discipline of rhythm. In this respect, use the metronome as a discipline, but play against it. Playing with the metronome is a mere mathematical calculation. Ride the rhythm, don’t let it ride you.”

Conductors should recognize the essential distinction between tempo and rhythm. Tempo, as the constant pulse, establishes the musical frame and must not be distorted. Rhythm might be defined as one way of seeking the expressive quality in music within that musical frame. Music is a living entity and as such it should never become entirely mechanistic. Rhythm brings music to life. Rhythm is a subtle fluctuation, a feeling of departure and arrival between the musical line and the basic tempo. The composition may have the right tempo, according to the metronome, yet the rhythm may still be off because of incorrect accents and stress patterns.

An explanation given by Toscanini speaks to the importance of maintaining freedom in the music while maintaining a tempo. In a conversation with Samuel Antek, Toscanini explained that it was expressiveness within the tempo that gave the music life.

“Toscanini held up his hand and in the palm he traced a diagram to illustrate what he had been talking about. He drew a vertical line. ‘This,’ he said, ‘is the tempo,’ and then across weaving in and out sinously he traced a wavy line, like a snake wrapped around a stick. ‘That,’ he said, ‘is the way the tempo must change – weaving in and out, but always close and always returning, never like this,’ he said, drawing a line away from the original line, at a tangent. ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘in music, just to have the correct tempo without all that goes with it means nothing.’”

Therefore, even with careful attention, tempo remains a fluctuating element. Bernstein once suggested that “perhaps a musician’s individual metabolic rate has something to do with it, since metabolism would control his rate of breathing, his pulse and therefore his sense of timing.”

Elizabeth Green similarly observed, “the human being feels most at home with his natural tempo, the tempo of his heartbeat.” Therefore, the conductor should be wary of natural tendencies that may influence the tempo and should carefully select the tempo demanded by the music.

Sometimes, however, the performers are not able to achieve the proper tempo. This often happens with young musicians, and for them the following advice from composer-conductor Vaclav Nelhybel is helpful:

“Choose the tempo in which the players are able to execute all the notes with all expression markings; if the chosen tempo is either slower or faster than indicated in the score, compensate with dynamics by over-emphasizing all expressive markings in fast movements, and deemphasizing slightly in slow movements. Whatever the situation, a logical relation between tempo and dynamics must be maintained. Without it, a convincing performance cannot be achieved.”

I believe strongly that singing is a very helpful and expressive way to determine the proper tempo. When sung, the melody usually will connect to the tempo that reveals the emotional expressivity in the music. Instead of the ensemble performing a series of individual notes, singing gives flow, shape, and expressive nuance to the musical phrase. But most of all, singing brings about inner learning that opens the door to a musical interpretation.

Many famous musicians have taken the same view and have offered their ideas on establishing tempo through singing. Beethoven once said: “Good singing was my guide. I strove to write as flowingly as possible.”

Herman Scherchen, conductor: “Of all the human means of musical expression, singing is the most loving or vital. Singing comes from within ourselves. The conductor’s conception of a work should be a perfect inward singing.”

Weingartner: “No slow tempo should be so slow that the melody of the piece is not yet recognizable, and so fast that the melody is no longer manageable.”

Toscanini: “There is no music without singing. Cantare Sempre.”

In conclusion, while it is true that a metronome indication may supply an accurate clue to tempo, one must remember that it is intended only as a guide, not as a command to maintain metronomic rigidity. In the hands of a skilled conductor, a musical performance will give the illusion of perfectly timed beats without any sacrificing of the freedom of the music.

Eric Bloom has pointed out the two requisite skills for superior interpretation: “The idea of true tempo covers the technical qualification to be a conductor; the idea of the melody covers the ideal aspects of the art.” It is the conductor’s job to meld these two elements, tempo and melody, to create a convincing interpretation.