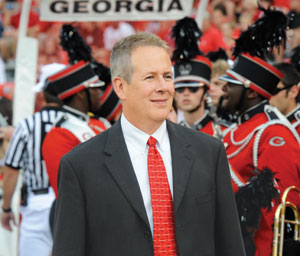

John Lynch, director of bands and professor of music at The University of Georgia, is quite well-known as both a conductor and a conducting teacher. Says Lynch, “My philosophy of teaching conducting hinges upon three areas: physical technique and nonverbal communication; score study, including analytical and aural skills; and rehearsal strategies and teaching from the podium.” Now in his third year at Georgia he conducts the Wind Ensemble, assists the Redcoat Marching Band, and administers the band program. He also teaches applied graduate conducting lessons and a seminar every week. Lynch previously taught at the University of Kansas, Northwestern, and Emory University as well as in high schools for ten years.

John Lynch, director of bands and professor of music at The University of Georgia, is quite well-known as both a conductor and a conducting teacher. Says Lynch, “My philosophy of teaching conducting hinges upon three areas: physical technique and nonverbal communication; score study, including analytical and aural skills; and rehearsal strategies and teaching from the podium.” Now in his third year at Georgia he conducts the Wind Ensemble, assists the Redcoat Marching Band, and administers the band program. He also teaches applied graduate conducting lessons and a seminar every week. Lynch previously taught at the University of Kansas, Northwestern, and Emory University as well as in high schools for ten years.

What are the overlooked aspects of the physical side of conducting?

Tension is something incoming graduate students and conductors in general seem to have in common. This gets in the way of showing the music physically, so we immediately work on ways to release tension, which everyone holds in a different part of the body. Tension limits expressiveness.

Jerald Schwiebert at the University of Michigan works frequently with conductors but is actually an expert on human anatomy. He says that a fluid motion requires using as many joints as possible. Many conductors only move the arm while the rest of the body is still. This looks artificial and stiff, because moving the arm across the body normally causes the rest of the body to move to accommodate the shift in weight. Conductors should move not just their arms, but the entire body to produce the fluidity that we see in the most graceful conductors. All motions in conducting start from the center of the body, which in Eastern philosophy is right around belt level. With many people you see a lack of connection between the motion they’re making with the arms and the rest of the body.

Conducting is an interesting discipline because conductors make no sound. Conducting teachers often talk about looking like the music, but Robert Spano, the conductor of the Atlanta Symphony, says, “More importantly, we want to create the gesture that elicits the sound that we imagine.” That could mean that a gesture doesn’t really look like the music, but it gets the sound that you want. The most important thing is the sound we get, not how we look. Even before I work on technique with students, I make sure they have a strong aural image. Only then does conducting become a matter of using gestures and the body in the most expressive and communicative way possible to get the desired sound.

How should conductors develop ideas about the sound they want?

Score study combines years of musical study with an idea or point of view. Some people say that what’s in the score is in the score and that’s it, but I don’t agree. I think Pablo Casals said it best: “About 60% of what is in music is actually on the printed page.” I share that quote with students and then ask where the other 40% comes from. The answer is that it comes from themselves. As conductors, we bring our perspective as musicians to every piece. Interpretation should be within the context of the period, style, and practice and shouldn’t be so far removed that it doesn’t sound like the composer. That being said, conductors who don’t infuse a work with their own ideas come up short.

I ask classes to listen to a recording of Rostro-povich playing the first movement of the Bach First Cello Suite in C major. We go through the score phrase by phrase while listening and talk about things Rostropovich did that made the score come alive. These include rubato, tone color, and placing weight on certain notes. Going through a recording of an expressive artist makes it easy to measure the contributions of musical interpretation. Conduct-ing students can try those things that they heard in their own interpretations.

I often compare shaping a musical line to language. When we speak we use inflection, emphasis, pitch, and pacing as dramatic elements. Music should be the same way. We also talk about the three ways in which music moves: pressing forward, relaxing back, or in repose. I give students a melodic line and have them sing or play it, deciding on the focal point of each phrase, which notes to stress, and the ones to relax.

Developing a strong concept of ensemble sound is also essential. As part of the conducting audition I play recordings of the same piece played by two bands with a dramatically different sound. The candidates have to discuss what they hear, what the differences are, and which they like best.

What areas should conductors spend more time addressing?

The way we give instructions and interact with people from the podium are an important part of conducting but don’t always addressed in conducting study. Conductors cannot make music in a vacuum; they rely on good communication with others to make music. Master teachers exhibit three traits. The first is having extremely high expectations and setting high standards for students. The second is taking an interest in every individual in an ensemble, both personally and in their musical development, which is sometimes difficult with a large ensemble. The last one is passion for and knowledge of your subject area.

Conductors who want to evaluate their technique should record themselves conducting both a performance and a rehearsal. A concert shows skill at nonverbal communication and how much energy you can generate. A rehearsal tape shows how you hear, how you communicate what you hear, and your skill in fixing problems. A portion of the graduate conducting audition is designed to assess these things. Candidates have a scripted 20-minute audition with the wind ensemble. The first few minutes they run through a piece so I can see how they establish a relationship with the ensemble and how well they communicate nonverbally. After that, I’ll have them work through something I noticed about their conducting. That tells me how open they are to input and how quickly they learn. In the last couple minutes they can rehearse anything they didn’t like from the run-through. That remaining time illustrates efficiency and rehearsal skill.

What is the best way to build a strong program?

Great music teachers or performers are not always the most talented, but rather the people who don’t give up. They learn from mistakes and keep trying. You can often learn more from mistakes than from success. My first teaching job was as an assistant band director at a big high school in New York state. It was a diverse school, and I was assigned to teach a new class called Music In Our Lives, a required high school general music class. There was no curriculum, and I was coming in with stars in my eyes, excited to have a job and ready to inspire students about classical music.

Great music teachers or performers are not always the most talented, but rather the people who don’t give up. They learn from mistakes and keep trying. You can often learn more from mistakes than from success. My first teaching job was as an assistant band director at a big high school in New York state. It was a diverse school, and I was assigned to teach a new class called Music In Our Lives, a required high school general music class. There was no curriculum, and I was coming in with stars in my eyes, excited to have a job and ready to inspire students about classical music.

I prepared a lesson on Mozart for the first day, but these were tough students who didn’t want to hear it. They walked all over me. I had a terrible time of it; the first week was a nightmare. After being extremely discouraged, I rethought my strategy and decided to find something they were interested in and could relate to.

Everyone loves music, so I asked the class what type of music they listened to and why they liked it. Their answers sparked a change in my approach to this class. I actually received a small grant to buy guitars for the entire class and started teaching some basic chords, how chords worked, and how lyrics express thoughts and feelings, using music that they liked. Students brought in recordings of their favorite rock groups (at the time it was heavy metal bands), and we analyzed those pieces at a basic level. The class had much more relevance, and in the end I taught some important musical concepts with the students’ favorite music.

When you come in to a new situation, you have to assess where that program and those students are, and help take them from point A to point B. Of those three elements that I cited, the one that’s most important to all of this working is taking a personal interest in and building a personal connection with each student. This may be as easy as taking a minute to say hello and ask how they’re doing. If you know that students are interested in something outside of band, ask about that. The fun part of teaching is getting to know the students. When I student taught in Indiana, one talented trumpet player gave me all kinds of grief because he was bored. We butted heads frequently until I finally sat down with him and picked his brain. I asked what he liked about music and whether he wanted to play the trumpet after high school. It took a little while to develop a rapport, but it definitely helped.

Once those connections develop over time the other things become possible. If you’re a new teacher placing demands on students, it’s not going to work. Students need to know first that you care about them.

You can set reasonable expectations when you begin and then gradually increase them. Every day I try to raise the bar a bit. Students are happiest and most excited when they feel like they are learning and growing. Giving them attainable goals and setting standards a bit higher each day, each year, will end with greater music making. Directors should also model what they want from students by being passionate and working hard. People notice when a teacher is willing to do what he asks of others.

What is the most important part of mentoring future teachers?

It is important to show them that you believe they can do well. There is nothing more powerful for students than having someone they look up to believe that they can accomplish their goals with hard work. This also helps when they hit the valleys, especially in the first year of teaching. A good number of teachers quit after the first year, but if they have the voice of a mentor in the back of their minds, it can be enough encouragement to persevere when things get difficult.

That happened to me in my first year as a doctoral student. I had a wonderful mentor, Eugene Corporon, who pushed me extremely hard and had very high expectations. I wondered if he thought I didn’t have what it took, but I found out a year or two later that he said I was one of the most talented students he’d worked with. I didn’t realize it at the time, but having that knowledge gave me great confidence and motivated me to do many things.

Part of mentoring is helping students find their ideal career path. That too comes from getting to know the students, seeing their strengths and presenting a variety of different scenarios to them. Sometimes I come up with an idea a student has not considered, as was the case with a recent undergraduate who wasn’t sure whether she wanted to pursue music performance or music education. We found out she had an aptitude for arts management, so she took her talents in that direction. Not everyone has to take a traditional path.

An undergraduate music education major may not be sure what level he should teach. So many want to be high school band directors, but some people are more effective with middle school students because of their energy, passion, and enthusiasm. Extremely patient and detail-oriented people often work well with beginners. I remember a person who student taught in high school band but fell in love with elementary education.

Students at the graduate level know what they want to do, and I expect doctoral candidates to have a very clear idea of where they want to end up. Even then, I try to expose them to working with athletic bands or give them a taste of being a director of bands. It all comes down to getting to know students well and having them share and then refine their goals.

What are the biggest differences between choral, orchestral, and wind conducting?

The basic skills involved are the same for all three types of ensembles. The differences are in the individual techniques of how the instruments or voice produce sound. The variance is in the rehearsal process – understanding the physics and physical differences of how that works. A choir director needs to understand diction, vocal placement, and head voice versus chest voice. A band director must know how wind instruments work and the acoustics of wind and percussion instruments. Orchestra conductors need to be knowledgeable about string techniques, such as bowing. The actual technique of conducting is the same, though. We teach a basic conducting technique common to all disciplines.

A band director who learns in summer that he is also responsible for the choir next fall should study with someone who understands voice rather than worry about his conducting technique. Knowledge of your particular discipline is extremely important. I’m a woodwind player, so I’ve spent a good portion of my career picking the brains of professional brass players and friends who are brass pedagogues, so I can be the best brass teacher I can possibly be. The same is true for percussion. The people who are really knowledgeable about how each instrument works have a great advantage. One might argue that at the professional level you’re not going to teach people how to play their instruments, but for school teachers, this is essential knowledge. I would even argue that although you might not tell a professional how to play his instrument, it aids a conductor in understanding what a problem is. If a passage isn’t working, it could be a simple articulation issue, something that you wouldn’t realize without that knowledge base.

I was invited to guest conduct a professional chamber orchestra in Alessandria, Italy last December. It took me back a bit because I haven’t conducted an orchestra in years. I had to prepare well and do rigorous score study to figure out how I wanted things bowed. The musicians didn’t notice that I wasn’t a string player.

When you conduct school groups, what trends, both good and bad, do you see?

There is a lot of sharing of ideas by top directors and programs. Improving a program is not a matter of resources. There are proven ways to succeed. The best directors focus on fundamentals of sound production at the youngest levels and spend a lot of time being very careful about the embouchure, hand position, and the basic sound of the instrument. They emphasize good habits and don’t let bad things slip by; this produces a rock-solid foundation.

It takes longer in the beginning because directors have to be more patient and use more repetition. That’s tricky because you have to keep the students interested too, but once students have that foundation, they take off in years two, three, and four.

I’ve noticed that students tend to be most successful if directors steer them toward an instrument for which they have a timbral affinity. That’s why you see tuba players who double on upright bass or sing bass, or people who sing soprano and play instruments that usually play the melody line. If you can capture that in beginners they have a better chance of success.

A general problem I’ve noticed is a lack of variety in programming and an overemphasis on the latest, flashiest pieces. Because the music we select is our curriculum, I feel that it is important to program a broad range of high-quality music, keeping in mind the standard masterworks of the band repertoire and the great composers. Our medium is band but our subject is music.

When did you become interested in composing?

I took a composition course at Eastman while doing my master’s work. My teacher, Sam Adler, was encouraging and suggested I try it. The more that I work with bands the more I learn what works, what doesn’t, and how to write idiomatically for the instruments. That knowledge plus the ideas I’ve always had motivated me to try writing a piece. I wrote my first composition while at Emory University in Atlanta about 12-13 years ago and premiered it with the Atlanta Youth Wind Symphony and later recorded it With the Emory Wind Ensemble.

I learned quite a bit from the first piece about developing and writing transitions, which are really difficult. I wrote my second piece while teaching at the University of Kansas and have a third one, a theme and variations, in the works. I only have time to compose during summers and on vacations, so if I come out with one every five years I’ll be happy. Composing is simply a matter of wanting to express myself in a different way. It’s fun and exciting to create something where there was nothing.

If you were going back to the public schools, what would you do differently?

I would strive to have more balance in my life. The most effective teachers have a life outside of their jobs. As a high school band director, my life was my job for ten years, and that isn’t healthy. We bring more to our students each day if we have time to recharge our batteries and have a rich life outside of work.