A classic article from February 1988

William Hebert once painted a silver piccolo black to fool George Szell into thinking it was wood. He has appeared on stage wearing concert dress of white tie, tails, and black earth shoes. When asked what he thinks about during the tacet first two move-ments of the Tchaikovsky Fourth Symphony, Hebert responded, "Where should I plant my peas?"

William Hebert once painted a silver piccolo black to fool George Szell into thinking it was wood. He has appeared on stage wearing concert dress of white tie, tails, and black earth shoes. When asked what he thinks about during the tacet first two move-ments of the Tchaikovsky Fourth Symphony, Hebert responded, "Where should I plant my peas?"

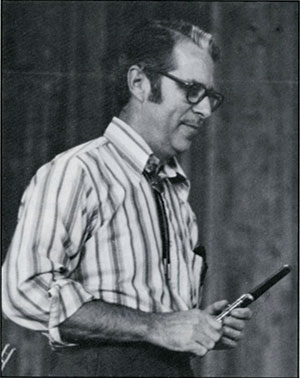

Like a rare coin, there are two sides to Hebert’s personality: on one side, he is a proper Bostonian, a disciplinarian, a musician upholding the highest standards of the profession; on the other, he shows a sense of humor combined with patience and softness.

Hebert has been the piccolo player of the Cleveland Orchestra since 1947. He has taught flute and piccolo for over 25 years at Baldwin-Wallace College. His students hold positions in leading orchestras and institutions across the United States. Examples of Hebert’s superb piccolo playing can be heard on the many distinctive Cleveland Orchestra recordings made during his 41 seasons. In addition to his love for music, Hebert is an avid farmer and manages an organic farm in Chardon, Ohio.

Hebert is famous for his personalized approach to teaching. Brian Gordon (piccolo, Phoenix Symphony Orchestra) expresses the sentiments of former students: "William Hebert seems to be a man truly in balance – serious and devoted, yet having a sense of humor and a carefree attitude. In both teaching and playing, he’s able to analyze to the millimeter and impart a natural sense of musicality." Judy Ormond (piccolo, Milwaukee Symphony) notes that he is always able to sense the weaknesses of each student and provide tremendous direction. Don Gottlieb (piccolo, Louisville Orchestra) recalls asking if every flutist should strive for a crystal-clear tone. Hebert’s answer: "I can tolerate a little garbage in the sound, but you’ve got the whole city dump."

Hebert has influenced many piccolo players in orchestras today. Deidre McGuire, Hebert’s assistant at Baldwin-Wallace College for 17 years, says, "He always finds some creative methqd to build a well-balanced, well-polished, confident player out of each individual." Florence Nelson (piccolo, New York City Opera) states, "Hebert gives you a sense of pride in the instrument." Lawrence Trott (piccolo, Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra) remarks, "I am sure that I became a piccoloist because I studied with Bill Hebert." In a recent interview some of the topics Hebert discussed were piccolo technique, teaching at Baldwin-Wallace College, an audition for George Szell, and his years of experience with the Cleveland Orchestra.

Should every flutist have some experience learning to play the piccolo?

With rare exception, most flutists play piccolo during their training years. In any professional position a flutist is required to play piccolo at some time. My students at Baldwin-Wallace spend the winter quarter of their sophomore year on piccolo. I do this because as freshmen they spend too much time developing embouchure, breathing, and other fundamentals of the flute. During the junior and senior years, students are busy getting ready for recitals and auditions.

Is the piccolo embouchure tighter compared to the flute embouchure?

Oh, no. That’s a misconception. The piccolo embouchure is further forward. The piccolo sounds an octave higher than the flute so the hole between the lips has to be smaller. Players shouldn’t compensate by tensing up the jaw, the neck, the scalp, or the ears. I use the same basic embouchure to produce the second and third octaves of the flute as I use for the first and second octaves of the piccolo. The difference comes in the low octave of the flute and the high register of the piccolo.

What about the common complaint: "I can’t play the flute anymore after I’ve practiced piccolo?"

I sometimes come away saying that. I think it all depends on the way you practice. I have a colleague in the Cleveland Orchestra who is the second clarinet as well as the E flat clarinet player. I’ve heard him warming up, and he has a unique way of practicing. He’ll play an F major scale on the B flat clarinet and then immediately pick up the E flat clarinet and practice the same fingerings. He practices both instruments in tandem, and he always sounds terrific on both.

For me, the type of challenge I have from week to week determines what I concentrate on. If Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony is coming up, I practice double-tonguing with the metronome set up to quarter = 160 a good ten days to two weeks before the concert. If the program includes a Shostakovich symphony that has some high notes marked pianissimo, I practice a lot of long tones and slow arpeggios. If we’re playing "Dance of the Mirlitons" from The Nutcracker Suite, however, I play a lot of low register articulation on the flute.

In general, someone who might be put on the spot from week to week to play either instrument should practice both instruments in a systematic fashion. I often get calls from former students who want a brush-up lesson because of an upcoming piccolo audition for some orchestra. They start practicing piccolo only two weeks before they arrive and wonder why they can’t compete. It’s got to be an on-going process.

What advice do you have for young professionals taking piccolo auditions?

Two things are of utmost importance: good intonation and the ability to play softly in the high register. It’s gravy if you can get a beautiful sound. In a major symphony orchestra there are three flute positions and one piccolo position. For every flute audition there may be 150 flutists who try out, but for a piccolo audition, there might only be 25. The odds of winning favor the piccolo. Of my students who play professionally, I would say two out of three play piccolo to flute.

I think you can develop an attitude about the instrument. After working with the piccolo for a while, you realize it is an instrument in its own right. It is not just a baby brother to the flute.

What are the intonation problems on the piccolo?

Assuming the player uses a professional quality instrument, held in the proper position and supported at a constant mezzo forte level, there should be few notes that are out of tune. However, there is a tendency toward flatness on the notes Bflat2, B2, C2, D#2, and D2, especially in pianissimo passages. The position of the cork and air stream have a lot to do with correcting this. Players should be careful with instruments that have a cylindrical bore; although its response may be easier, the pitch is not nearly as good as on those with a conical bore.

What about the position of the head cork in the piccolo?

Theobald Boehm measured the ideal position for the head cork on the flute at 17 millimeters from the cork to the center of the blow hole. This ensures that the octaves will be reasonably well in tune. The piccolo sounds an octave higher than written, so we can assume that 8.5 millimeters from the cork to the center of the blow hole should work for proper octaves. Some professional players, however, alter the position of the cork to produce a particular sound quality or color. Most of the time I play on my wooden instrument with the cork in the middle. Sometimes I move the cork slightly to the left because I can get a fatter, darker tone. By moving the cork toward the C# key, the tone becomes brighter, and the articulation speaks more easily.

I prefer a darker tone quality to a piercing one. The piccoloist has to know what he’s doing because moving the cork alters the octaves. He should learn to correct this fault by aiming the air higher or lower and by using alternate fingerings. The changes are very slight: on the piccolo, a quarter turn of the crown makes a big difference.

Do you have any favorite exercises or studies for developing technique and tone control on the piccolo?

I’ve had to overcome many other problems, but I’ve been fortunate in that I never have trouble with facility. In that respect I’m probably not a good teacher for someone with a serious coordination problem, because I didn’t have that difficulty. I had to learn everything else. Practicing scales and arpeggios with the aid of the metronome builds technique on the piccolo just as on the flute. It’s easier to play fast on the piccolo. The instrument is smaller and the fingers and the keys don’t have to travel so far. Technique is not the hardest aspect of playing the piccolo. To develop tone control, I use the Trevor Wye tone book, Taffanel-Gaubert played in slow motion, crescendos and diminuendos, and I work a lot with a tuner. I also love to use the Ferling oboe studies, the first book of Genzmer’s Modern Etudes, and Andersen, Op. 33.

Which teachers influenced you the most?

When I was in high school, I studied flute with James Pappoutsakis, who was the second flutist in the Boston Symphony. What a marvelous person and a beautiful flute player. He was the one major influence on my flute playing. I never took a piccolo lesson in my life. I listened, experimented, and learned on the job. It’s been said that the definition of a good musician is one who is a virtuoso listener.

You have been teaching at Baldwin-Wallace College since 1950. Have students changed over the years?

They’re better today. The level of woodwind playing in the United States is the best in the world. Each year the new students are better trained and have better instruments. Attitudes have changed, too. Students are more practical, and they want to be marketable. If appropriate, I encourage a student to get a background in education, or perhaps major in the sciences.

Do you enjoy teaching?

I thrive on it. I enjoy working with people who are serious and willing to work. I am basically a problem solver and have always been intrigued by why things happen. In teaching I have to come up with different explanations and solutions for different people. I enjoy a student who is serious, intelligent, has at least a modicum of talent, and lots of problems to solve. Intelligence is important: I have to be able to appeal to a student’s intellect in order for change to occur.

You use a lot of analogies in your teaching, don’t you?

Oh, sure; I tell jokes and stories, too. Here is a point related to teaching: it takes only about five minutes for an orchestra to size up a guest conductor. Of the 15-20 categories we might put him in, the first question is whether he is making music with us or at us. So, when I teach, I try to make music with the student. Although I show him how to play I am also participating in the process. I don’t sit on a pedestal and dictate how it should be done.

I also insist that my students keep notebooks. Years later many students tell me how they still refer to them for information. If I had a nickel for every word written in those notebooks, I’d be rich.

On the subject of orchestral playing, how do you view your role as a piccolo player?

The piccolo is part of the flute section, of course, but most of the time it’s soloistic. Very little writing uses the piccolo either as a part of the flute section or as one voice in a chord that is supposed to blend. Most of the time the piccolo is in a leadership role.

This is your 41st season with the great Cleveland Orchestra. Tell us about your audition for George Szell.

I was finishing up at Juilliard and I saw the notice for the third flute/piccolo opening posted at the National Orchestral Association. At that time, just after World War II, few flutists were interested in playing piccolo. Szell came to New York to hear auditions, and there were six people trying out. There was no committee, just Szell and the manager. I had brought all my orchestral excerpt books. They were all copied by hand because there weren’t many published then. I had one Wagner book, one Strauss book, and one Shostakovich book. None of the other excerpts was published. I had written to George Madsen, the piccolo player in the Boston Symphony, and he sent me a list of what Szell would most likely ask for. I went to the library and copied them all by hand and then memorized them.

At the audition, Szell asked me to play six times a few things including the Tchaikovsky Fourth, which he heard from six different places in the auditorium. Then he said, "Well, it looks like I don’t have anything to give you to sight read because you have all the solos in these books. Maybe I can find something." He opened his briefcase and took out an opera part to Die Walkure. It was the "Fire Music," which takes four players in the section to do, two flutes and two piccolos. In this edition, the two piccolo parts were combined, so there was no place to breathe. The separate parts were in my Wagner book. In the middle, Szell started to conduct. He slowed down and sped up, and I followed him closely.

Szell stopped and remarked to the manager, "I want this man." Then he questioned, "Oh, by the way, do you play flute?" I later learned that when given a choice as to which instrument the other auditioners preferred to play first, they had indicated the flute. I said, "This is a piccolo job, isn’t it? I’ll play piccolo." Szell never heard me play flute until after the audition. That was in May, 1947.

It turned into a steady job, 41 seasons. What are some of the highlights that come to mind?

When you look at a painting on a wall, the whole work is in front of you. You see all of what the artist was trying to do. Unfortunately listening and performing music is not like that. Often you don’t appreciate a work until after it has gone by, unlike gazing right at a painting. There are many things that stand out. In 1965, the Cleveland Orchestra made a five-week tour of the Soviet Union. We were the first American orchestra to travel there. Before we left I spent a year and a half studying Russian. I took five copies each of the Griffes Poem and the Kennan Night Soliloquy to give to the principal flutists of the orchestras in the five cities we visited. When the orchestra travels abroad, I always try to go to conservatories and listen to lessons. I exchange music with other flutists and bring back recordings.

Then there was the Szell era, 1946-70. He was a musical giant. Working for that guy was a tough job. He was a perfectionist and a disciplinarian. He would spend hours in a rehearsal discussing the length of a dot or dash, but the concerts were superb. After 25 years, his musicality filtered down to all the musicians in the orchestra. They assumed his approach to music making and passed it on to their pupils as well. Whether directly or indirectly, one man made such a difference.

I wish everybody aspiring to be a professional musician could be as lucky as I have been. When I was young, I didn’t consider teaching; that was something to do when I got old. All I ever wanted to do was play in an orchestra, and that’s what I’ve been doing for over 40 years. Teaching talented young students started slowly in those early years and developed into an important aspect of my life.

Doing what you like to do is one way to avoid ulcers. I also have a lot of irons in the fire besides music making to keep me happy, such as

my organic farming – but that’s another interview.

Editor’s Note: William Hebert died in San Diego, CA on June 18, 2017 at the age of 94.