What led you to the flute?

Are your parents musical?

My parents are not professional musicians, but my mom grew up playing the piano, violin, and guitar. My Dad played the trombone through high school but never pursued it to any degree. My sister Heather grew up playing the piano and violin. She was quite good, making it into the competitive Norwalk Youth Symphony. My Greek grandfather, however, was the real musical influence on me. He was a baritone and trained for many years to become a professional opera singer. Despite his passion for music and singing, his career didn’t quite pan out because he was expected to get a real job when my grandmother became pregnant with my mom. They were quite poor and living in Manhattan when my mom was born. He continued to drum up musical concerts and shows throughout the years at his banking and real estate workplaces.

I actually spent every day after school until I was nine years old at my grandparents’ home while my mom worked. I remember lying under the piano, feeling the vibrations, and being enveloped by his rich voice and wonderful accompaniment. I could sense his passion for music and felt sorry that he had not been able to fulfill his dreams. I vowed that I would take the torch and be the one who made it professionally as a musician. I am forever grateful to my grandparents for buying us an upright piano and other instruments and paying for our weekly private lessons. They enriched our lives by providing us a musical education and exposing us to classical music.

Who was your first teacher?

My first teacher was Carol LaRusso, the wife of my band teacher in Weston, Connecticut. She was quite helpful in giving me additional exercises and assignments, as the flute came fairly quickly after having learned piano for three years. After moving the next year, I studied with Emily Chow, a very advanced high school flutist and the sister of a soccer teammate. I was inspired by her because she was young and talented, and I recall hearing her warm up on jumping harmonics which is something that I integrate into my daily practice to this day. Once she graduated, I studied with her flute teacher, Laura Tittemore Piechota who took me to a new level of playing. She helped me play more confidently and gave me the fundamentals that I needed. She instilled in me a desire to work harder and not rely on my talent alone. Moving to St. Louis for my last two years of high school meant searching again for the right teacher. It took a little while, but I eventually found Marie Jureit-Beamish at Principia College who was exactly what I needed. She was very tough and assigned me a lot of work and motivated me with exercises she learned from James Galway, Thomas Nyfenger, and Frances Blaisdell.

Did you go to summer festivals as a student?

I went to a number of summer festivals, but Centre d’arts Orford in Canada was life-changing for me. It was where I first studied with Robert Langevin in 2003 and then returned for nine more summers. I did not know who he was when I was first accepted into his masterclass, but figured he must be good if he was the newly appointed principal flutist of the New York Philharmonic.

Attending Sarasota Music Festival in 2007 was another wonderful summer festival. I learned some important standard orchestral repertoire and played woodwind quintet music coached by Julie Landsman of the Met. I especially loved learning from Carol Wincenc, Leone Buyse, and Thomas Robertello that summer. They helped take me to a new level of playing and gave me many new ideas.

In 2009 I attended the National Orchestral Institute (NOI) which focused mostly on orchestral repertoire, and I absolutely loved it. Later in 2012, I attended National Repertory Orchestra (NRO), a truly unforgettable experience in Breckenridge, Colorado. This festival felt like a professional orchestra, performing two programs a week for eight weeks. I loved the intensity and independence there, as well as hiking and running in the mountains.

Practicing at her grandfather’s piano

How did you select your educational path?

Due to moving around so much as a kid and attending a boarding school, I was not quite ready for the conservatory schools as options for my undergraduate degree. My college auditions did not result in what I had hoped for, but deep down I knew I needed to put in more hours of practicing instead of relying on natural talent. I decided to attend Principia College in Illinois to continue my studies with Marie Jureit-Beamish for four more years. It was everything I needed to grow, and it was a wonderful flute studio to motivate me. Although I was accepted at the Manhattan School of Music for my Master’s Degree, but lack of scholarship funding led me to the University of Miami where I was a teaching assistant. I got paid to teach undergraduate non-performance majors and perform in the graduate woodwind quintet. This also led to my first professional job as principal flute with the Miami City Ballet.

I still wanted so much to study with Robert Langevin weekly, not just in the summers at Orford, and before long I was accepted for a third degree in Orchestral Performance at Manhattan School of Music. Each school gave me invaluable tools. Principia College pushed me towards mastering my instrument and performing frequently; the University of Miami gave me the ensemble and chamber music opportunities I needed, as well as teaching weekly lessons to college students; and MSM pushed me to master excerpts and orchestral repertoire and throw myself wholeheartedly into the audition circuit.

Robert Langevin is considered one of the finest flutists and teachers of this time, what were lessons like?

Robert Langevin is special not only because of his gorgeous sound, singing vibrato, and heartfelt expression, but also because he is one of the nicest, most humble people you will ever meet. He is the epitome of a world-class musician: confident in talent, yet not egotistical. He teaches by demonstration in lessons but also by example in real life.

At MSM, our weekly lessons were actually in front of his entire studio, like a masterclass. He did not teach his Juilliard students that way, but felt that he gained so much when he had had these open lessons as a student in Germany, Switzerland, and Montreal. He asked us if we were willing to try it, and we were. We showed up well-prepared and left inspired.

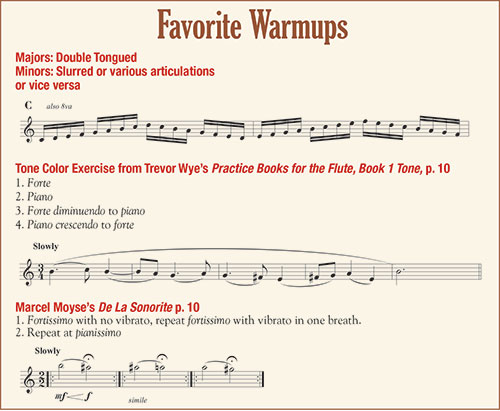

In lessons, Robert would often start off hearing his scale patterns which extend throughout the entire range of the flute, as well as the assigned etudes (typically Altes and Boehm). Often, he would also reinforce his fundamental concepts with exercises from Trevor Wye Vol. 1 and Marcel Moyse De la Sonorite. Additionally, we were welcome to bring excerpts and repertoire for whatever audition, recital, or competition we were working towards. Robert tells me that he currently teaches some lessons privately (working on scales, tone, and etudes), while the rest are open to the studio, creating a kind of mock audition.

With Robert Langevin

What was your Detroit audition like?

Auditioning for the DSO was tricky the first time around. Having subbed with the orchestra for a few years, I unintentionally put a large amount of pressure on myself as I was pretty attached to winning the job. It resulted in a no-hire, but I learned from it and changed my approach completely the second time around. Clearly, just practicing the excerpts was not enough. I understood now that I needed to work more on the mentality behind auditioning, especially when it was an orchestra in my own city. About 12 weeks before the audition, before even pulling out the excerpts again, I began working with a coach to break through the mental blocks that seemed to keep me from playing my best when it counted the most. This, combined with Sharon Sparrow’s 6 Weeks to Finals method, and doing many, many mock auditions helped me to arrive at the audition feeling more confident without any attachment to the outcome. I knew I was absolutely good enough to win, and yet I also knew that I had no control over what the committee was looking for or how they would vote. My goal was simply to play my best. This resulted in one of my best auditions ever in the semi-finals, leading to a final round and then an additional round with the DSO flutists. Five months later, I was offered the job after a one-week trial.

My advice to those auditioning is to not take the psychological aspect for granted. Visualize yourself on stage, work on self-talk, and find a coach if that helps. Read books about it and don’t just bank on practicing alone. Remember that it takes more than just playing the right notes to set yourself apart at the audition. Be musical and take risks that are not offensive. Show that can play ppp in Daphnis and ff in Petrouchka. Have your interpretation of each excerpt, while also striving for perfect intonation and rhythmic pulse. Explore colors and vary the vibrato. Prepare in a way that shows that you can do anything on the flute. Then, let go and just treat it like a recital.

What is different about playing second flute?

It is a completely different role and skillset than playing first flute, yet both require an incredibly high level of playing. A second flutist has to adjust to whatever the principal is doing, which means being flexible enough to do any type of vibrato speed and depth, any color or dynamic, timing the entrances right, and knowing when to play equal or less, soloistic or blended. As a second flutist, I would often find that my two principals wanted completely different things from me, so it required that I play one way on the first half of a program and then the complete opposite on the second half.

What are your duties in the DSO?

Piccolo is included in my contract as there are many pieces where two or more piccolos are required. The DSO audition list included a number of piccolo excerpts, and I believe I played them all in the final round of the audition. It is helpful to have a second flutist that is very good on piccolo because if Jeff Zook is sick or needs a vacation week, for instance, I can step in.

Due to having had a DSO principal flute opening for a while, the past year has resulted in my playing quite a bit of associate principal flute with Sharon Sparrow as Acting Principal. This has been a wonderful opportunity for me to get back to my roots as a principal player and to explore my own musical ideas, colors, and phrasing. I have also played alto flute quite a few times, regardless of the position I have been sitting in. The best advice I have for an aspiring orchestral flutist is to excel at all three of these instruments because you become a more valuable asset and are more likely to win a job.

What do you focus on with college students?

After teaching at Oakland University for eight years, I have worked with Sharon Sparrow and Jeff Zook to develop a curriculum for a high-level flute studio. All students are expected to attend required concerts, subscribe to Flute Talk, and prepare a solo work for the end of the semester flute studio recital. In addition to other assigned etudes, repertoire, and required degree recitals, my students work through Taffanel and Gaubert’s 17 Daily Exercises, Reichert’s 7 Daily Exercises, and Wye’s Vol. 1 Tone.

Additional technique books are utilized depending on which of us is leading studio class each semester, such as Paul Edmund Davies’ 28 Day Warmup Book and Geoffrey Gilbert’s Sequences, among many others. In my studio class this fall, students are preparing extended scales to be ready to play in class with an assigned goal tempo to target by the end of the semester. They are also required to perform in studio class a minimum of two times per semester with a pianist, usually followed by the university’s weekly Arts at Noon recital program. Of course, students must also perform a jury at the end of the semester as well.

I am a firm believer that to get better at performing we must perform as much as possible. This is what helped me to become more confident in front of an audience. Dr. Jureit-Beamish required me to perform weekly as well as give a solo recital each semester at Principia College. She helped me go from a shy kid to a natural performer, and this is what I hope to give to my students as well.

How do you stay in shape or warm up each day?

Due to needing to be able to do anything as a second flutist, I developed my 5 Daily Exercises to keep me in top shape. I did these by ear for many years, but I finally put them into Finale about a year ago after students kept asking for them.

As a true Langevin student, I believe that fundamentals should take up half of one’s daily practice total. Just like eating your veggies, this provides the nourishment you need as a flutist. Plus, once you get to the dessert (repertoire), it is much easier to play well and learn quickly.

What do you think about to produce your beautiful sound?

For me, tone is the most important aspect of playing the flute and my favorite topic to discuss and teach. Tone always came naturally to me, I am not exactly sure why, but I do know that listening to Kim’s well-trained flute playing in Sunday School gave me a clear model of what the flute should sound like. I also tried to have a clear sound like James Galway, who I listened to throughout my childhood.

After graduate school, though, and while I was playing principal flute in the opera, I decided to give myself a bit of an embouchure makeover. Nothing dramatic, but I realized that my corners were tighter than necessary, and my aperture could be more round. I thought about how Robert Langevin and many French-speaking people talk, so I gradually brought my corners closer to my canine teeth. I relaxed and dropped the jaw during long tones, opened the throat, and worked to see how relaxed my lip muscles could be without dropping the sound or losing focus. I immediately felt I had much more resonance to my sound and then worked to build that muscle memory. I maintain this today with harmonics, Moyse/Langevin Long Tones, and Trevor Wye Vol. 1 Tone. As I say to my students, “less is more.” Focusing more on support and less on the embouchure is the ideal balance for a beautiful sound.

Is there something that you wish you had done differently in pursuit of a professional career?

I have no regrets about anything in regards to my career. However, before I won this job, I was very tempted to feel that if I had practiced more in middle and high school or not done sports, for instance, I could have won a job earlier than I did. It is tempting to compare ourselves to others, but I am a firm believer that each of us is where we need to be, and if we make the most out of every single experience and learn from it, we will inevitably grow and succeed.

I was discouraged at times, however. Before graduating high school and finding Marie Jureit-Beamish, I felt very lost at my boarding school without my parents to guide me. For a few months, I considered going into interior design but deep down I knew that this was more of a hobby. Fortunately, my band teacher did everything she could to help me find the right teacher, which was all I needed to remember how passionate I was about the flute.

Later on while attending Centre d’arts Orford for my first summer, I could see that I was behind the many Curtis and Juilliard flutists who were my age or younger. They were clearly better than I was, but instead of giving up or putting myself down, I used this to gauge my progress. I would go back to Principia College and work hard at my weaknesses. Each summer I came back to Orford and saw the gap between myself and these flutists narrow and eventually disappear.

I am a very positive person but I still have occasional struggles or doubts. I think it’s important to stay positive and actively choose to look at the good going on in our lives and profession. I also have hobbies outside music that bring balance to my life. I love exercise of every kind, whether it be running, yoga, weight-lifting, or any outdoor sport. It keeps my me strong, fit, and happy. I also love decorating and gardening. I find it incredibly therapeutic to plant new flowers and weed in the garden. I also love traveling abroad with my new husband Brett.

Blaikie has taught at Oakland University for eight years and also teaches privately, coaches advanced flutists on orchestral excerpts, and is actively involved in the DSO’s Community and Educational Outreach Program. This past year, she was invited to be a flute faculty member at the Pacific Music Institute in Hawaii and has presented masterclasses at Interlochen Center for the Arts, the Hawaii Flute Society, and the University of Michigan. She earned her B.A. at Principia College, M.M. at the University of Miami, and a Professional Studies Degree in Orchestral Performance from the Manhattan School of Music. Her primary teachers include Laure Tittemore Piechota, Mare Jureit-Beamish, Christine Nield-Capote, and Robert Langevin. This summer she will teach alongside Robert Langevin at Centre d’arts Orford in Canada in July 2020.