One can only imagine what a Brahms flute sonata would have sounded like had he lived to write it. It was possible. He had already started down the road towards writing wind pieces with his composition of the two clarinet sonatas very late in life, and the flute gained popularity as a solo instrument during Brahms’ lifetime (1833-1897).

One can legitimately argue that the flute never would have been able to express the range of emotion that a composer such as Brahms required, but one cannot claim that Brahms lacked the ability to write beautifully for the flute. Throughout his symphonic works the flute writing is just too masterful. For example, in the finale of the Symphony #4 Brahms gives one of his most expressive symphonic passages to the solo flute. That solo may in fact be the focal point of the entire symphony, Brahms’ culminating symphonic work. Given the lack of serious solo writing for the flute by composers of that style and period, the depth and beauty of Brahms’ flute writing is all the more striking. It reveals what seems to be a special feeling for the intimate and personal voice of the instrument.

Simple Brahms

In spite of flutists’ intense focus on the playing of specific orchestral passages for auditions, it is ironic that sometimes our depth of knowledge about those works suffers. There is no substitute for the “sound of knowledge” that comes through the instrument when a player has not only overcome the instrumental challenges, but has close acquaintance with the entire work at hand. This knowledgeable interpretation is manifest in myriad tiny nuances which are closely related to the player’s ideas about the piece and may not be discernible to the casual listener.

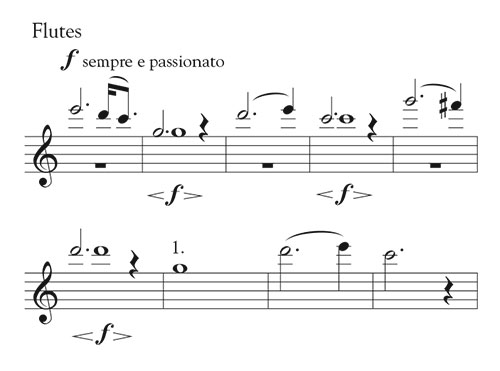

Nevertheless, some orchestral passages appear so straightforward on the surface that they do not seem to warrant special attention. The solo from the fourth movement of his Symphony #1 is a case in point. The brevity and apparent simplicity of the passage, composed of long notes dovetailed with the second flute, conceals music of great importance and layered meaning. A thoughtful look into this very well-known solo, in context of the entire symphony, can result in subtly beautiful qualities of performance and greatly enhance one’s appreciation of the work.

Surprise Solo

Brahms began work on a symphony in 1852, but it was not until much later, in 1868 that he apparently stumbled upon the focal point of the First Symphony, an idea on which the entire piece would rest. This is of course the famous C major melody that rather suddenly emerges in the introduction of the 4th movement.

Brahms in 1853

In a card to Clara Schumann he wrote a sketch of the tune, a simple alphorn theme he overheard in the mountains, with the inscription: “Thus blew the shepherd’s horn today!” The words to the melody are: “High on the hill, deep in the dale, I send you a thousand greetings!”

Looking at the orchestration, it is entirely natural that he gave the melody to the horn. For anyone not already familiar with the piece, it might seem that no repetition of the melody is necessary, allowing it to stand alone as a sort of monument in the symphony. Then the transition of measures 47-61 would immediately follow, leading to the 4th movement proper. All would be well.

Clara Schumann around 1850

However, in a surprising stroke of genius, Brahms has the flute repeat the tune which alters the energy of the passage entirely. It is a curious choice, given the boldness of the melody; it is hardly gentle or supplicating in nature. Perhaps the clarinet would be more the expected wind instrument, if any, to play such a melody, but I believe Brahms may have had several motivations for writing for the flute in such manner.

Note to Clara

One simple justification for choosing the flute for the solo could be text painting. The horn represents a greeting from “Deep in the dale,” followed by the flute statement coming from “High on the hill.” The passage is highly spatial in character. Also, noting the fact that the tune was first heard by Brahms issuing from a shepherd’s alphorn, it seems natural that a complimentary version might follow using another instrument traditionally played by shepherds, the flute.

The flute solo also could exist for more personal reasons. Looking at it in the general context, we are dealing with a symphony which it took Brahms decades to write. It was heralded as the next truly great symphony after Beethoven’s Ninth, and Brahms felt the full weight of that tradition. Brahms, an immensely self-critical composer, was only able to complete it after gaining confidence in his orchestral writing, beginning with the successful German Requiem in 1868. He also had steadily grown closer to Clara Schumann following the death of Robert Schumann in 1856. If the melody represents Brahms’ greeting to the entire musical world through the traditional voice of the horn, the following more individual, gentle voice of the flute rising above the orchestral din might have been a more personal note to Clara.

Profound Flute

Either way, in the context of the entire fourth movement the effect of the flute solo, occurring just before the famous main theme of the finale, is profound. The mood of the last movement seems somehow lighter and more uplifting in spirit because of it.

Whatever the reason for the flute solo, Brahms did turn to the flute to express the cornerstone idea in this most important symphony, as he would again in the Fourth Symphony. It seems that with the First Symphony, Brahms not only developed his first truly great idea in the symphonic form, but found appreciation for the depth and personal expressive abilities of the flute as a solo instrument.

Performance Notes

Understand It

Play the flute solo with generous and abiding passion, like a grand anthem. Do not try to mimic the character of the horns who play the theme first; that instrument lends its own character of heroism to the moment. The flute has a lighter, more personal voice. It is the lyric soprano to their stentorian baritone. The tone needs to be full and rich, but without force or aggression. The register works to your advantage. With the brass voices scored lower and in the distance against the background of rustling strings, no other voices intrude into your airspace.

Feel It

In performance, the excitement of playing such a great piece is palpable. There is an electricity in the air. If playing alone or in an audition, a little imagery can help establish the atmosphere. Conjure the scene, as in one of those dark, dusty old Romantic paintings. In the fading light of day, shepherds call and answer on their alphorns. Birds fly into the distant mountains. Imagine something like that, or, really whatever works for you.

Play It: Your To-Do List

Do not lose your feeling for the solo by practicing the following aspects. Hone and strengthen your voice so you play with authority and commitment to your idea.

1. Vibrato can be quite intense. Whether faster or slower, it should permeate the tone. All the notes need not start directly with vibrato; there is a quality of yearning to the melody.

2. Avoid accents or rude articulation. Start the notes exactly on time, but instead of simply starting the notes with common tonguing, a gentle puh with the lips, with plenty of air pressure and velocity will establish your lyrical approach from the very beginning of the notes.

3. Within the forte dynamic, allow the phrase to rise and fall naturally in intensity. Measures 1, 3, 5, and 8 are active, with the long note intensifying to the change of note on beat 4. Measure 5 is the high point. Measures 2, 4, 6, and 9 are notes of relative repose (the second flute has their gentle swell in those bars). The G of m. 7 extends the phrase and leads into m. 8.

4. Beware of the tendency to play sharp in pitch. Avoid overblowing the notes by seeking focus and resonance.

5. Avoid shrillness in the tone by relaxing the jaw and embouchure and employing maximum air velocity.

6. In an audition, be compulsive about rhythm. It is easy to slow down the long notes or begin the notes behind the beat.

7. You trade alternate measures (m. 2, 4, 6) with the second flutist. This can be tricky, delicate work, as tone and pitch must blend when transferring the notes. Allow the second flute to create the crescendo in those bars, and get out of the way by reducing vibrato and dynamic. When playing alone, do not exaggerate these chamber music nuances.

For a younger player, it is very easy to neglect this solo or take it for granted because it looks so simple. Realize that in a Brahms symphony, all passages are crucial, but the flute solo of Brahms’ First Symphony is singularly iconic. It not only represents a great Romantic composer’s coming of age in the symphonic genre, it is a cornerstone of the orchestral flutist’s repertoire.