Taking up your well-worn copy of the Mozart G major Concerto flute part, which feels a bit like the proverbial ball and chain, you once again disappear into the recording hall to lay down another take for your annual summer music festival applications. Your heart is not exactly soaring at the thought of playing the piece yet again. Sound familiar? If we are honest, many of us have a case of Mozart-itis and the prognosis is not good: only more Mozart.

Our beloved Mozart G is also our curse. It has become the test piece for every flutist. If there is one single piece a flutist must play really well, it is this one. Unfortunately, it has the nasty habit of revealing your private flaws, as if you are standing there in only your knickers. Being tired of the concerto really makes things worse.

Hard Questions

Since the only solution to the problem seems to be to improve your playing and to appreciate the piece more, flutists should start with some basic questions. Why is playing the G major concerto so difficult? Why do flutists become bored with it, instead of appreciating it more with repeated performance? Why does it seem strangely awkward? The answers are elusive. In spite of the fact that you have taken the piece into lessons repeatedly, and your teacher has diligently and patiently labored with you on every phrase, why does it still not easily take flight? You might even feel that it is just not a great piece and wonder why committees keep asking flutists to play it.

Tough Stuff

Going back to the original line of inquiry, it is hard to play the piece because, well, it is really hard to play Mozart’s music well. Some years ago, during rehearsals of Mahler’s 8th Symphony, one of the largest symphonies ever composed, I once asked the famous conductor how he could conduct such a gigantic difficult piece. He said, “Yes, it is difficult, but not as hard as Mozart.” On another occasion, a colleague suggested that we simply stop requesting it on audition lists because there was so much poor playing of the piece. After many years of reviewing audition tapes, I must admit that he had a point.

Before you go into that recording studio one more time, let us discuss some ways in which you can make the first movement, Allegro Maestoso, of the Mozart G major shine the way it deserves.

Tune It

Small intonation flaws and bad habits become major blemishes here. For example, the octave in measures 31-32 should avoid the typical, flatness on the high D natural. C# in the middle register must be in tune, not sharp. This will require extra attention and consistently proper embouchure placement, such as in measures 60-66, where the C# occurs often as a passing tone.

Measures 31-32

Measures 60-66

Even it out

Prevent distortion within the beat, especially when executing consecutive patterns 16ths with the 2-slurred 2-tongued pattern. Unevenness in this pattern causes many flutists to add false accents, by stressing the first note of each slurred group, as can easily happen in the first bars of the flute line.

This habit can wreak havoc on the attempt to play a long, continuous phrase shape. Often, slurred notes are stretched, and the tongued notes are compressed, creating an odd limping feel. Especially with regard to quality of articulation, avoid noisy clicking or hissing sounds when tonguing because they are not musical. Do not crack the notes because, well, it is ugly.

In Time

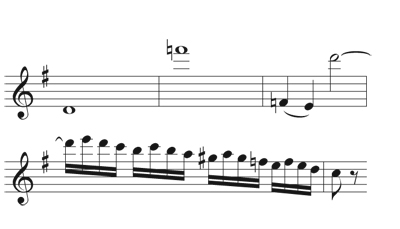

This music requires no changes of tempo or rubato. Many players rush in the fast movements. Also common is the tendency to play different phrases or phrase groups at slightly different or inconsistent tempos, as is common in measures 46-53, shown below.

You can play the piece exactly in time with a metronome, and as long as you play with beautiful phrasing and tone, there is no sacrifice in musicality. Sometimes rushing comes from an exaggerated sense of bravura or showiness as a substitute for a more natural spirited energy with good phrasing. Bravura and virtuosity have their place in all of Mozart’s music, but they emerge from the heart of the piece, at the right moments. The trick is to recognize those moments and put that energy into perspective.

Your Best Tone

Mozart’s music requires a consistently focused, buoyant, and beautiful sound at all times. Any lack of purity, noisiness, or lack of resonance is immediately apparent. Vibrato should be rational, and not disproportionate in the sound. Too much vibrato and the playing sounds hysterical or interfering. Not enough and it sounds mechanical. Registers should be balanced. If the high notes are loud and screeching in character, or if the low notes are not full enough, there is lack of proportion and linearity to the melody. This can happen very easily in passages where there are octave transfers, such as in measures 107-111.

Measures 107-111

Energize It

Generally the energy is high in a Mozart fast movement, with lightness of spirit, and floating, dreamy, or dance-like in the slow movement. The Allegro requires not only a fastish tempo, but a projection of excitement. This must come from inside the player, as a personalization of the energy. Do not confuse this energy with simply playing fast to achieve fireworks. The air column should be active at all times and never sluggish in nature.

Musical But Subtle

In terms of phrase gesture and shape, balance is critical. The long, continuous melodic groups are constructed of smaller, slightly contrasting character groups, which should be seamlessly knitted together. Contrasts are usually made apparent after careful study of subtle changes in the harmonic, rhythmic, motives, and melodic changes in the accompaniment.

For example, study the constantly shifting accompaniment in measures 46-53, on the previous page. Do not romanticize and over-phrase, but also do not ignore subtle changes in character ranging from uplifting and energetic, to tender and reflective, as they occur rapidly within the same group of phrases. Avoid self-aggrandizing and banal bravura gestures and unnecessary virtuoso display. For example, in the first entrance of the flute, start with a balanced sense of Maestoso without being heavy and ponderous. Then play the following descending 16th note scale with elegance and lightness, without adding aggressive accents. End the first phrase expressively without accenting the last note.

No Extra Baggage

The reason for insisting on all this control and rationality is that the music is composed with utmost economy, intention, rationality, and proportion. There are no unnecessary notes cluttering the phrases or clouding the figuration or character. As a result, it is quite logical that for the purposes of competition, this music efficiently separates those who are capable of playing with such fine discrimination, control and balance from those who are not.

Familiarity Breeds…

If you are feeling bored with the Mozart, it might be good to take a break from it. Even better, take time to look deeper into the music. A healthy reminder to respect the composer may be in order; any fault we find with Mozart lies within ourselves. Many flutists do not give Mozart his due simply because they are tired of practicing the flute part. Much of the music in the concerto is actually not there; it is in the accompaniment. Try playing the flute part in such a way that you react to changes in the orchestral part. Become better acquainted with the singular genius of Mozart by listening to his operas and piano concertos and then applying those impressions and conclusions to your playing. If you listen patiently and closely enough, you can find enough music in the G major concerto to last a lifetime.