American flutist Helen Bledsoe won the first prize in the 1996 Gaudeamus International Interpreter’s Competition for Contemporary Music. She subsequently has performed as a soloist and ensemble player in Europe. She teaches at the Conservatory of Bremen (Hochschule für Künste), and for the last fifteen years has been a member of Ensemble musikFabrik, based in Cologne, Germany.

Ensemble musikFabrik is a chamber orchestra with strings, single winds, a percussionist and two pianists. The sixteen-member group performs regular concerts as well as theatrical works that include choreography, acting, and singing. The group often breaks into smaller ensembles for chamber music or solo presentations. They commission composers, give regular workshops for young composers, and participate in pedagogical projects with students of all ages. Their concerts focus on interdisciplinary projects that have included live electronics, dance, theater, film, literature, visual arts, along with chamber music.

Ensemble musikFabrik is self-governing so the artistic direction lies in the hands of the musicians. Through their innovative programming the ensemble has collaborated with many prominent conductors, composers, choreographers, and opera directors.

How did you become a member of Ensemble musikFabrik.

How did you become a member of Ensemble musikFabrik.

Normally we have an audition process, where the vacant post is announced in the German Magazine Das Orchester. In my case though, I met members of the ensemble in 1996 at the Darmstadt Summer Courses and was asked to sub. When their flutist decided to concentrate on orchestral activities with the Berlin Radio Symphony, they asked me to replace him. I started working with them directly after getting my Artist Diploma in 1996.

What interesting experiences have you had with this group?

Being an ensemble member is not just about playing your instrument because we all help with programming, pedagogical projects, and working with composers. Being an oldest child, I have an annoying didactic nature which can actually be put to good use in workshops the ensemble provides for young composers. However, I find that even experienced composers sometimes need to be reminded about instrumental techniques and good notation.

When you combine modern music and theater, there can be many surprises. In 1998 we performed Maricio Kagel’s Mare Nostrum in Lisbon. Only at the open dress rehearsal did I realize one of the costumes for the male lead singer included his birthday suit! I have also had some very strange costumes. When we performed the premiere of Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Sonntag aus Licht for the Cologne Opera we wore nuclear waste clean-up suits, complete with galoshes because we were actually playing and dancing in several inches of water, live microphone cables and all. I also had to strip, on stage, from the clean-up suit to a dancing costume while counting rests.

We have played many wonderful projects in beautiful settings. I loved playing Georgy Kurtag’s Poems to Anna Akhmatava in the Opera Garnier, Paris. Kurtag is a notoriously exacting composer who is rarely satisfied with performers. Although I never played the little flute solo to his liking, he had the grace to shrug his shoulders, smile and thank me afterwards.

Heinz Holliger is another hair-raisingly tempermental composer, but playing his haunting piece “(t)air(e)” in Amsterdam’s Congertgebouw was wonderful. Another theatrical piece we premiered was Stockhausen’s Rotary Quintet in the beautiful Schloss Dyck. I had thought the piece rather banal, but the audience went crazy, one woman even came backstage weeping, saying to the composer that she had never experienced anything so moving. Just goes to show that you should not judge a piece too soon.

Doing theater and multimedia can be fun, but I prefer to challenge the boundaries of my musical and instrumental abilities. We are a soloist ensemble, and are expected to be involved in solo projects. When I heard Dialogue de l’Ombre Double for clarinet and live electronics by Pierre Boulez I could easily imagine transferring those fantastic musical characters onto the flute and bass flute. Arranging and learning this piece was a great lesson in patience, doggedness, imagination, and slow, slow practice. The clarinet has a fantastic scope for expression, it has been developed and improved by generations of fantastic players. The bass flute has a relatively short history and I was hard put to match the technical and musical artistry of a good clarinet player. It was fun trying, and I hope to publish the recording this year.

What is your schedule like?

We perform about 80 to 100 concerts a year, mostly concentrated in the fall, when many European Festivals take place. There can be periods when I have no days off for several months. For example in the fall of 2006, I played ten different programs on three continents within three months. Some of these were my own solo projects in addition to the Ensemble’s performances. Since my son was born in 2008, however, I have slowed down.

What pedagogical work does Ensemble musikFabrik do with students.

This Spring we will give three workshops for student composers studying in Düsseldorf, Essen, and Warsaw. The students’ teachers choose the scores, we sight read them, devoting ninety minutes to each. It is a great opportunity for students to hear their work and get feedback from their teacher and the musicians. We try to provide a friendly open environment where the students can learn from each other as well.

We also work with students in the community. Sometimes one or several of us will adopt a music class in one of the public schools and work in tandem with the music teacher for several years. In Cologne they also have a program called Kinder Uni (Children’s University). Small groups of children attend rehearsals and a concert with a given subject to consider, such as music and pictures, or electronic sounds or world music. The children then do a report, either audio or video (nothing written), and attend workshops led by ensemble members where they create their own music based on what they have experienced. Sometimes they even build instruments. We have a great African amadinda (xylophone) that was crafted with the help of children.

How did you become interested in contemporary music?

When I was sixteen, I entered the University of Pittsburgh. The music department did not have much of a performance department, but was very strong in composition and musicology. I would hear graduate students talking among themselves. They would say such things as Schonberg’s Op. 33, is a good piece, but this other modern piece is terrible. I thought it all sounded terrible, but decided to investigate further. I learned more about contemporary music when composition students would ask me to play their pieces. I also met Robert Dick my second year there.

How did you prepare yourself to perform contemporary repertoire?

How did you prepare yourself to perform contemporary repertoire?

I was introduced to multiphonics by my teacher in high school, Dan Leonard. Meeting Robert Dick and playing his music and studies provided a mix of inspiration and method for learning extended techniques that worked great for me. I was also fortunate enough to do two fall residencies at the Banff Centre, Canada, where I focused on extended techniques. The first session I worked with Aurele Nicolet and at the second I worked with Robert Dick. Preparing contemporary music is like learning any other music; you have to be sensitive to style because there are different, even historical, performance practices within contemporary repertoire. An added bonus, however, is that if the composer’s intentions are obscure, you can often just ask him. Playing contemporary music is not just making funny sounds. There may be extended techniques to deal with, but contemporary musicians who do not extend their knowledge of styles, and sense of rhythm and intonation do so at their peril. When working on a contemporary piece, one of the most important questions you should ask is why the composer uses a specific technique? How does it flow in the piece? Does it function in any formal way? I find it useful to not only know the composer’s other works, but to go to the source of his inspiration.

What techniques do you use?

Harmonics are probably what I come across most in the literature and use most for practice. I also use multiphonics, singing and playing, and all different kinds of air sounds and percussive noises either with keys or with the mouth, like tongue ram or tongue pizzicato (done either on the lip or the hard palate).

How did you learn to improvise?

My high school teacher, Dan Leonard, made me improvise, and Robert Dick was also a big influence. I listened to all his recordings and those of his colleagues too, including saxophone player Ned Rothenberg. I have had the huge honor to play and record with terrific German sax players like Matthias Schubert and Frank Gratkowski. My main partner in improvisation is Russian pianist Alexei Lapin. We hope to make a duo recording sometime in 2012.

Who were your first flute teachers?

I began in the Boston-area public school music program. When my family moved back to South Carolina where I am originally from, I had private lessons with Teresa Texeira and Dan Leonard in Charleston. It is really Dan Leonard I have to thank for becoming a musician. At the age of fourteen, he told me that “What you want to do, you can achieve.” Later at the University of Pittsburgh, I studied with Martin Lerner and eventually Bernard Goldberg. I majored in music and minored in French and Russian.

What were lessons like with Goldberg?

Bernard Goldberg (retired principal flutist of the Pittsburgh Symphony) was quite methodical. I dutifully played many etudes (Berbiguier, Altes, Donjon, Andersen) and some Bach Sonatas (e, E, b), and of course there was Taffanel & Gaubert too. His love was for the French repertoire (Faure, Gaubert, Saint-Saens). He was very particular about articulation. I remember working an entire summer just on articulation.

Whom did you study with at Indiana University for your master’s degree?

At the time the school had a special arrangement in which Peter Lloyd and Kate Lukas had open studios. We could take lessons with either one, alternating weekly or by the semester. Peter Lloyd was great for me. He was impressed by what I had learned about French repertoire with Goldberg and helped me develop my articulation further, open up my sound, become more confident, and develop my own musical ideas. Kate Lukas knew the contemporary repertoire, and it was with her I first studied Brian Ferneyhough’s Cassandra’s Dream Song and the Berio Sequenza.

Why did you go to Europe?

While studying in Pittsburgh, I heard a concert of Harrie Starreveld, who is flute professor at the Amsterdam Conservatory (then called the Sweelinck Conservatory). I wanted to study with him. Starreveld is a fantastic teacher of all styles, especially the 18th century repertoire. As the flutist of Amsterdam’s Nieuwe Ensemble, he also is a crack contemporary music expert. He accepted me as a student. I had also been accepted by Pierre-Yves Artaud as a student at the Paris Conservatory, but I think I made the right decision in choosing Amsterdam, where the society is more open and welcoming of outsiders.

The Conservatory in Amsterdam offers a program called “Contemporary techniques through non-Western music.” Through this program I met a wonderful singer, Jahnavi Jayaprakash, who invited me to India to study with her. I spent several weeks in Bangalore, making a pitiful attempt to play the pullankulal, a south Indian bamboo flute. In India I learned so much about microtonality and complex rhythms that relates to the contemporary music I play today.

Was living in Europe a big change for you?

Was living in Europe a big change for you?

Not as big a change as one might think. My family moved frequently and it was easy to move again. I had experienced different cultures and dialects within the U.S., having lived in the deep south as well as New England. I had one semester of German as an undergraduate and discontinued studying it because I couldn’t say anything without laughing, it sounded so funny to my ears. I learned Dutch when I moved to Holland and lived with a Dutch family my first year. By the time I started working with musikFabrik, my Dutch was good enough that I could understand German well. I became fluent, if ungrammatical, by just being immersed in the language.

When I teach at the Hochschule, I teach in German. I occasionally give masterclasses in St Petersburg or Moscow and teach in Russian. My husband is from Russia, so Russian is our house language.

What do you teach at Bremen?

I team teach at Bremen with Harrie Starreveld, who is now a professor in Bremen as well as Amsterdam. He invited me to teach with him in 2005. Starreveld and I alternate teaching the students. He teaches one week and I teach the next. We have anywhere between five to ten students at a time from all over the world. Starreveld gives private lessons and a masterclass. When I am there, I teach private lessons, a techniques class, and alternately a class on contemporary repertoire and orchestral studies. Orchestral studies are becoming more important in Bremen because of the new Orchestral Academy. Our students play at least one concert a year with the Bremen Philharmonic, which is fantastic experience. There is an active new music department with many talented composers, a contemporary ensemble, and a well-equipped electronic studio.

We do not have a fixed schedule of solo repertoire for the students. Solo repertoire may include Baroque sonatas and fantasies, the Mozart concertos, Nielsen, Ibert and Reinecke concertos, and the French Conservatoire pieces, but the specifics are decided in private lessons. Etudes (Anderson, Paganini, Boehm, Bitsch) are covered in technique class. At technique classes, each flutist performs his etude in front of the class. For this class I also compose studies for harmonics, rhythm, and intonation.

As far as contemporary solo repertoire goes, I assign that on an individual basis, bearing in mind that there are five 20th century pieces every flute student should be familiar with: Debussy’s Syrinx, Varese’s Density 21.5, Berio’s Sequenza, Toru Takemitsu’s Voice, and Elliot Carter’s Scrivo in Vento. These compositions cover a lot of ground and styles as preparation for 21st century music.

We provide a general flute education, although we have had graduate students who specialize in contemporary music. We hope to offer a specialized masters degree in contemporary music soon. We introduce contemporary techniques to undergraduates from the start. I think it is a mistake to introduce harmonic multiphonics only when students are ready to play the Berio Sequenza. As Robert Dick said in a masterclass recently, you don’t learn D major by playing Mozart’s D Major Concerto.

How should students prepare for the future?

Be prepared to work hard and seek inspiration when it fails you. Be aware that working hard and playing well doesn’t entitle you to anything. It helps to be versatile, entrepreneurial and a good networker. In German there is a term, Eierlegende Wollmilchsau, that means an egg-laying, wool and milk producing sow. In other words, one animal that gives you everything. Ensemble musicians have always had to be versatile, fluent in different musical styles and able to play flutes of all sizes and make very quick changes. Today, orchestral musicians are facing this challenge too. There are opportunities for flutists to play in Baroque, contemporary and jazz ensembles that did not exist several generations ago. With the internet there are opportunities to present your talents to a wide audience as never before.

What kind of music do you listen to?

I enjoy the Baroque traverso players, like Rachel Brown and Barthold Kuiken. I like the Tuvan singer Sainkho Namtchylak. My husband enjoys Sun Ra and Frank Zappa. I always listen to the repertoire that I am teaching and playing. This could be anything from Beethoven’s 7th Symphony to Helmut Lachenmann’s Mouvement.

What flutes do you play in your work?

I regularly perform on the piccolo, C flute, alto and bass flute. It takes time to learn to switch from one to another quickly, but once you have a good technique on each flute, it becomes easy. I like Patricia Morris’ advice for practicing the piccolo. Morris says the flutist does not need to spend hours on the piccolo. Thoughtful, sensible transference of flute technique to piccolo regularly every day works wonders. I think this applies to bass and alto flutes as well. I prefer the sound and intonation of a straight alto flute. However, for comfort and projection, I play on a curved alto. Someday I would love to own both. It is fantastic to work with some open holes. I wish I had an open-holed piccolo, too.

Have you studied Alexander Technique or yoga?

Since I left music school, I consider my Alexander Technique and yoga instructors to be my best flute teachers. Great as most of my flute teachers were, they were not able to address certain issues I had with the physicality of making music. You have to be aware of what goes on inside you, of course, but it is also important to be aware of how you project your ideas on stage with your movements. It is a sad thing if your music is telling one story and your body movements conflict. In chamber music it is very important to give coordinated movements, especially for upbeats and pulses that your colleagues can follow. Exercise and yoga helps me keep the physical coordination necessary for this. Gyrating like a spastic windmill, like I used to do, only confuses your colleagues and make your audience seasick.

What are you working on now?

In May we will go to the U.S. where we will play music of Harvard composers in Boston. In Troy, New York we will play a concert with mixed media.We are also making premiere recordings of chamber music by Georgy Kurtag and Georg Aperghis in Cologne for the new musikFabrik label. I am playing in a new ensemble, a trio for flute, viola and harp called Trio Odilon. We have performed our program several times. Each time it gets better, but I want to achieve the ultimate beautiful Debussy Sonata. As both an individual and ensemble member, I am looking to create new works through commissions. One commission I am very excited about is with Rebecca Saunders, an English composer, who is writing a solo for bass flute that combines music and spoken text.

When I am not traveling, I spend time with my family, including my son who is three. Otherwise I read indiscriminately, anything from crypto or science fiction to Russian literature. I hope to finish Doctor Zhivago in the original Russian this year.

In keeping with my affinity for science fiction, to go where no one has gone before, I want to create music that is not there yet.

* * *

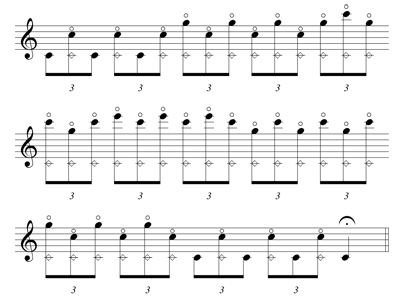

Bledsoe’s Harmonic Exercise

To play harmonics finger the diamond-headed note, blow to the upper note. Play at a tempo that is slow enough to be precise at a mf dynamic level. First practice slurred and then with t, k, hah, p. Repeat the exercise using a Db, D, and Eb as the fundamental note.

1.

2.