Editor’s note: At the time of this article (1987), Geoffrey Gilbert lived in DeLand, Florida and throughout the year taught a class of about 12 students. In the fall of 1986, Gilbert visited Evansville, Indiana to teach a masterclass for the newly formed Evansville Flute Society. The ages and abilities of the participants were greatly varied – from young players with poor playing habits to advanced players of professional ability. Gilbert gave his undivided attention to all of them. Although he did not normally teach beginning students, on this occasion he shared his thoughts on teaching the basics and the ground rules for good flute playing.

Gilbert was not an easy teacher. James Galway said in a Flute Talk interview around this time, "We can only raise the standard of flute playing by people teaching more intensely and refusing to have bad students." As one of Gilbert’s former students himself, perhaps Galway learned this philosophy in part from Gilbert. In the Evansville masterclass, Gilbert was patient, but unrelenting when it came to upholding the standards.

As each player came up on stage, Gilbert asked them to announce their name, piece, and what kind of flute they played. What follows here are his instructions to the young players, edited to read as though they were given to one student.

Blowing and Breath Support

The reason I made her repeat her announcement is because I knew pretty well from hearing her speak how she was going to play. There is no way you can get anything out of the instrument unless you put energy into it. You have to use breath pressure and keep it constant. You didn’t do it in your speech and you don’t do it in your playing either. That’s why your sound fades all of the time; you run out of energy. When you’re playing it’s an announcement, isn’t it? It’s just a communication in music instead of in words.

[The student plays again.] How long can you hold that note? You must time yourself. Take a breath and do that again. Nine seconds. You should be able to get to 50 – at your age! Every day try to go longer; but don’t try to go from nine seconds to 50; try to go from nine seconds to 11, or 10 seconds to 12. Just add a few seconds every day, then gradually you’ll develop greater breath capacity.

I’ve never thought that the ability to hold a long note depends on your physical size. It is the control that you exercise over your breath that is important. Have you got the Trevor Wye books? They are called Practice Books for Flute. I suggest that you get at least number one; there are a lot of tone studies in there that you need very badly.

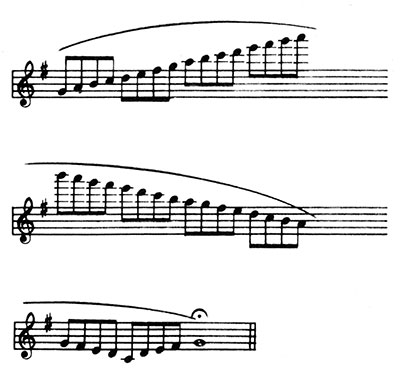

Breathing Exercise

Play the following exercise without vibrato. Do this starting on C, then B, Bb A, Ab, and G, until you get down to Db and C. You can’t play it too slowly.

Scales

This piece [Mozart’s Concerto in G Major] is too advanced for you. The first objective is to learn to play the flute before you start to play the music; then you won’t waste so much time. Almost all music that we play is built on the simple, basic elements of music: scales, thirds, and arpeggios. If you had learned to play these before you started working on the piece then there would be only limited portions of it you would have to practice.

So first of all I would like to hear you play a scale. Because this concerto is in the key of G, let’s play a complete scale in G, legato, which means slurred. The best scale system is in Marcel Moyse’s Daily Exercises. You should practice them all the time.

[The student has some difficulty playing the scale.] You can see now, can’t you, the futility of playing the Mozart Concerto when you haven’t yet learned the scale of G. That’s putting the cart before the horse, isn’t it? lf you play your scales every day and use all the notes on your instrument, up to the top and down to the bottom, you’ll develop your technique in the areas that need it. It’s the bottom register which is difficult to develop. The top register is supposed to be difficult, but it really isn’t. When you practice complete scales you become familiar with all of the notes in all of the registers, and there won’t be any problems. G4 is a very high note for you isn’t it? Get used to it. After all we can go up to D4, E4, or F4 at the top. There are many notes on the instrument that you are not using.

Rhythm

Now the next thing to do is to play in a time frame. You lost a lot of 16th notes playing the Mozart. Let’s play a scale in C and accent every fifth note. (He demonstrates vocally.) TA da de da DE da de da DE da de da DA. Blow a bit harder. Accent!

That’s better; but if you were playing with a metronome you wouldn’t agree with it, would you? That’s what happens throughout the piece. You’re playing the notes, but you’re playing without rhythm. Your pianist had a very difficult time following you – hurrying when you were hurrying and dragging when you were dragging. If you were playing this with an orchestra they wouldn’t do that. First thing you’ll have to do is learn to play in time. Do you have a metronome? (Student nods.) Do you use the metronome? (Student nods again.) What do you use it with, or for? You haven’t practiced the Mozart with the metronome have you?

Posture and Position

I haven’t said anything about your position, which is also very important. Now let’s just see if I can help you a little bit. Your position is very cramped. Your flute is too close to the right shoulder. You must get the flute away from the shoulder so that you are free. Also, your thumb sticks out beyond the flute so that it isn’t really holding the instrument up. That’s the reason you are having difficulty moving your fingers. You need to get your thumb underneath where it will do you some good.

Also keep your wrists underneath the instrument, not out here. Otherwise your little finger is very far away from the G# and C# keys, so every time you need to use them you have to bring your hand in, which is very awkward. Keep your hands tilted towards the right, not to the left, so that the little finger is long enough to reach these keys. You should be coming down on the keys, not reaching for them. It’s also always a danger signal to me if I see the mechanism turning in towards the player. The mechanism should be on top.

Stand well away from the music. Get the music stand as low as you possibly can. Unless you have eye problems, you should be able to do this. You’re supposed to look down with your eyes, not put your head down. All right? You’re bending forward. That’s not very good for breathing. Lean back a little more. That’s right.

Vibrato

We all have a natural vibrato; some people have a slow vibrato and some have a quick one. Whichever one you don’t have you must practice. My vibrato is naturally slow, so I have to practice all of the time to make it faster. People with really quick vibratos have to practice to make it slower; but you must practice vibrato because it’s not going to happen by itself. Otherwise you’re completely at the mercy of the instrument and do whatever it wants to do. You’re not really playing the instrument; the instrument is playing you.

Above all, listen to string quartets and to very, very good singers, preferably lieder singers, not opera singers. Listen to what they do and then copy that on the flute. You’ll find that in expression they are much better than we are. We very often model ourselves after wind players or other flute players, which is not always the best thing to do.

Intonation

If you find yourself playing sharp cover with the top lip, but don’t turn the flute in to make the pitch flatter; that’s the worst thing you can do. You lose half your sound and the pitch varies a great deal. When I say cover, I mean get the top lip more over the tone hole, then blow slightly more downward. Don’t make any mistake about that. Keep the key mechanism facing toward the ceiling; relax the jaw and get more space between your teeth. That in itself will flatten the sound without destroying the body of the tone.

Summary

You have to learn to handle the instrument. If you’re going to be a painter, for example, it’s not sufficient to have a row of paints and a brush; you have to learn to mix them all before you can create. It’s the same in playing a flute – you must learn all the basics.

It sounds rather formidable at the beginning, but it isn’t really if you think about it. You have a major scale and a minor scale in two forms; you have major and minor arpeggios, a diminished chord, a dominant chord, and an augmented chord. That is the whole of music in a nut shell. Everything you’re going to play is based on those few things. You can make a set of exercises that will cover the whole lot of them in 20 minutes once you get the technique down.

This routine goes on the whole of your life. I’ve been playing for 190 years and I still practice this routine every day; I never miss because it doesn’t take very long. That’s the reason why even in my advanced age I’ve still got a reasonable technique. Once you learn these things it’s like riding a bicycle or swimming, you never forget how to do it; but you must learn the basic techniques first. You’re trying to play the concerto before you’ve learned the steps you have to take to approach it.

I suggest that for the next few months or perhaps the next year you concentrate on these basic elements. Every day play scales, some tone studies, some technical studies, and then whatever else you have to do. The pieces must come at the end of your practice, not at the beginning.

The difficulty of the flute is to play it in tune and to play it with the right expression. To play the notes is not a great problem. If you spend enough hours practicing the right things you will acquire a technique.