I grew up in Minneapolis in a family of musicians – parents, uncles, cousins. My dad was a great trumpet player who free-lanced in the Twin Cities, and taught junior high band. My mom was a junior high vocal music teacher. She was also a talented painter, illustrator, poet, and writer. I was the oldest of four children, and our home was a fun and creative place to grow up. My parents inspired me with a passion for music, and I started the piano at age four. They also instilled a strong work ethic and the value of doing something you love and doing it well. In fourth grade I began playing the flute that my dad had bought when I was a baby and had tucked away in a drawer until I was older.

I never actually chose to play the flute. It was simply something I always knew was in store for me. While I don’t regret my dad’s choice for me, I have often secretly wished that I played the oboe, as I love its depth and dark color. (I think I would even like reed making.) According to my dad, I took to the flute like a duck to water although I vividly remember feeling faint and dizzy trying to get a sound out of it at first.

My dad loved Mozart, whose birthday we celebrated every year by making a cake. Each of us kids had to play something by Mozart before eating the cake. I also have fond memories of borrowing my dad’s baton, putting on an LP of Beethoven’s 7th, and standing in the living room conducting.

Emil Opava was one of my early flute teachers. He played principal flute in the Minnesota Orchestra and came from the Curtis Institute and William Kincaid. His powerful sound and exciting playing made a strong impact on me. My high school had a fabulous music program. The discipline and high standards instilled by our band director were inspiring, and I began to thirst for broader horizons and a real conservatory experience, which led me to Boston and New England Conservatory.

At NEC, where I studied with James Pappoutsakis, I found myself in the big pond for which I had yearned. I was excited to be there but also remember walking down the halls past practice rooms and hearing such impressive playing that I sometimes felt inadequate and behind. I took this as a challenge. My coping strategy was to get up early each morning and practice for a good two hours before classes began. I was determined to prove myself. My work paid off, and my confidence grew.

Upon graduating, I went to Paris for a year. I applied for, and was awarded a French Government Grant through the Fulbright Committee. I studied privately with Michel Debost and was part of an international group of musicians who were presented in concerts around Paris. This opportunity merged my love of the French language, art, and music. Being suddenly immersed in a foreign culture pulls the rug out from underneath a person and takes away all familiar points of reference. It forced me to learn many ways to adapt, rebuild, survive, and thrive. My world vision was greatly expanded.

What was Debost like as a teacher?

He was a wonderful teacher who emphasized stability – in stance, holding the flute, sound production, and technique. He demonstrated a lot, and it was a joy to hear his command and fluidity. If there was a difficult passage in the piece, he would say “Never work out your technique just on the piece, itself. Take the technical issue and make up your own exercises related to the passage. Practice other things that are similar, become so solid that you can then return to your piece and be able to play it.” He was a very generous and kind teacher. My lessons at his home would often end with lunch with his family. Early on in my studies with him, he invited me to turn pages for his Poulenc Sonata recording and afterwards took me on a tour of the Louvre. To this day I credit him with awakening my love of great art.

What did you do after the year in Paris?

I came back from Paris to NEC for my MM and to resume studies with Pappoutsakis. The week before school started, my roommate came home one day with a record and said, “Listen to this! There’s a brand-new flute teacher at NEC, Paula Robison. Here is her recording with Beverly Sills.” The moment the needle hit the LP, it was like that moment at the beginning of The Wizard of Oz when the house lands, and the movie changes from black and white to color. I heard a flute sound that I had never ever heard before. It was like the Siren’s call, and I had no choice but to heed it and immediately sought out Paula Robison. Little did I know then that she would become not only my teacher and mentor for life, but now my most cherished colleague and friend.

Paula is as gifted a teacher as she is an artist. She had me working out of Moyse’s Tone Development Through Interpretation – not just playing the opera arias, but going to the library to listen to singers. My goal became playing with the same lyricism and line, passion and drama, as the great singers I had been hearing. Moyse’s book became my Bible. Because Paula had worked on the book with Moyse, I was receiving a lineage of wisdom.

She always insisted on playing with clear intention and purpose. She made me go deeper into the music and into my own expressive powers, revealing a whole new world to me. She insisted on a tone full of life. It had to be colorful, beautiful and varied. I remember playing for her in lessons, finally achieving what she was after. She would then say, “Now do it again.’’ She wanted to make sure I fully understood how and what I had just done and could reproduce it. This is a hallmark of a great teacher: someone who has the dedication and patience to go back to square one if necessary and repeat the whole learning process if it has not sunk in.

The privilege of hearing Paula play so many recitals and concerts was a crucial part of studying with her. She breathed a logic, brilliance, and magic into everything she played. After hearing her, I felt I knew exactly what I wanted out of a piece.

After my official lessons with Paula ended, she continued to teach me over the next couple years for no fee. She said that Samuel Baron had done that for her years before on the condition that she do the same for someone else someday. That I could be her someone else was beyond my wildest dreams. She imparted to me the same condition that Sam had to her. It has now become a kind of chain letter out into the world as my students find their someone else and continue the tradition.

How did your professional career start?

Another pivotal moment in my life came during that year at NEC with Paula. She recommended me to a group of musicians at the Marlboro Music Festival in Vermont. A wind quintet of top players was forming, and they needed a flutist. I auditioned and became the flutist and founding member of the Aulos Wind Quintet. We moved to Philadelphia and were quintet in residence at the Curtis Institute. We were coached by Marcel Moyse and Sol Schoenbach, principal bassoon of the Philadelphia Orchestra. We were given professional management, tours around the country and invited to participate at the Marlboro Festival for many summers.

Performing nationwide with the Aulos Wind Quintet launched my career. We won the 1978 Walter Naumburg Chamber Music Award and commissioned the Quintet for Winds by John Harbison, which has become a staple of the repertoire. It was at the Marlboro Music Festival that I matured as a musician. The hallmark of Marlboro is that chamber groups are formed by combining young professionals with legendary musicians from around the world. The experience of rehearsing and performing alongside a world-class musician as a colleague is a game changer. Beautiful tone, robust espressivo, musical truth – these were strong values at Marlboro. I began to find my own voice.

How did you come to study with Marcel Moyse?

I met Marcel Moyse at Marlboro. He was larger than life and quintessentially French – debonair, buoyant, and elegant. He was also tyrannical, opinionated, and occasionally cruel. And, we all adored him. His French accent was thick, his sports coats hung loosely around his aged frame, but he was ever robust, mischievous, and passionate.

He would often sit with students after coachings at Marlboro with a glass of Pernod. He would regale us with stories of how he grew up as an orphan and shepherd boy in the French Alps, his first lesson with Gaubert and work with Taffanel, and his collaborations with Ravel, Stravinsky, and Debussy. He described in detail his rehearsals with a dying Debussy on the Sonata for flute, viola, and harp and how critical and exacting the composer was. He told us how he came to write Tone Development Through Interpretation after playing first flute in the Opera Comique. His goal with the book was to expand the flutist’s tonal and expressive range to that of a great singer.

I worked with Moyse at Marlboro and at Curtis in both chamber music settings and private lessons. I studied French repertoire including Syrinx, works by Mozart, and pieces from the great school of flutist-composers such as Boehm, Kuhlau, and Doppler. His metaphors and images were vivid, often related to nature, and always to the human experience. He demanded absolute attention to every detail as well as the big picture. A musician had to tell a story. A sonority had to be alive and colorful. Players had to have many tone colors up their sleeves, had to go the full spectrum from passion to poignancy, from drama to mystery. Above all, a person had to play with love. When carelessness allowed a harsh or raw sound to escape, he would say, “Kiss me, don’t kick me.” He could be derisive when someone played badly or indifferently, but his praise could lift you to heaven.

Moyse’s demanding approach was actually what made him such a great teacher. You did exactly what he told you – there was no other way. (You dared not, but you also trusted him completely.) After studying a piece with Moyse, your interpretation told a compelling story. Your tone had somehow acquired more radiance and depth as your expressive powers deepened. He left an indelible mark on all who worked with him.

How did you start your career?

I believe this point in life when one is fresh out of college and ready to start a career is the most difficult phase for any young musician. Just knowing that up front is helpful. Perhaps it was easier back when I was starting because the economy, rents, and status of the arts in general were more favorable than now, but it was still difficult. I never won that orchestra job I wanted, although I came come close a few times. Instead, I carved out a multi-faceted career in New York City that has been rich and rewarding. Along the way I have had many rejections, failures, and bad performances. These are part of everyone’s trajectory. I could fill volumes with my failures. I was also incredibly fortunate to have had mentors and colleagues who believed in me, opened doors, and gave me golden opportunities. I also always worked extremely hard to raise my standards, expand, and grow as an artist.

My career has been a series of stepping stones. I started freelancing in New York and built a solo, chamber music, orchestral, and teaching career. Some highlights were frequent performances with Paula Robison at the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center and at her Metropolitan Museum series, being a founding member of the Music Today Ensemble under Gerard Schwarz (performing newly written works and many New York and world premieres), chamber music with New York Philomusica, and solo recitals at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the 92nd St Y.

In 1987 I became principal flutist of the New York Chamber Symphony. The position had been Thomas Nyfenger’s, but illness forced him to resign. This was not through an audition, but by appointment from Gerard Schwarz with whom I had been working in the Music Today group. That experience taught me how to play principal flute in an orchestra. Schwarz was an important mentor for me and an exciting and great conductor. The season was substantial with glorious repertoire, including Beethoven, Brahms, Ravel, as well as many contemporary works. Each year around New Year’s, we performed the complete Brandenburg Concertos for five nights in a row. My tenure lasted through 2002 when the orchestra was discontinued.

A major turning point came when I started playing with the harpsichordist Kenneth Cooper. Making music with Kenneth was exciting and unleashed permission to be wildly creative while staying true to Baroque conventions and style. Kenneth’s unique mastery of ornamentation taught me how to color outside the lines. Kenneth is an impassioned virtuoso whose rhythmic vitality is unsurpassed. I became a founding member of the Berkshire Bach Ensemble, a core group of winds, strings, and harpsichord which performs regularly in the Berkshires and East coast.

What is it like playing with the American Ballet Theatre Orchestra?

My audition for ABT in 1996 was trial by fire – playing an entire eight-week season. I had never played ballet before then. I had to learn eight to ten different ballets including Swan Lake, Don Quixote, and Prokofiev’s Cinderella. The flute parts in ballet are huge and demanding with pages of pyrotechnical passages and high-wire acts as well as many beautiful, lyrical solos. They are far more dense than symphonic repertoire. I never worked harder in my life for anything. I learned each ballet as though it was a flute concerto, including every tutti passage, trying to get the right feeling and dynamic for every entrance. That season, I would see colleagues during breaks with snacks and coffee and had no idea where they got them. I had some vague notion that there was a cafeteria down the hall, but I never once went there. I just stayed in my chair reviewing the next act. Looking back I see this as a poignant indication of what the pressures can sometimes be like in the music profession.

Playing in ABT is thrilling and exciting. The repertoire is often glorious – Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet and Strauss’s Whipped Cream being at the top of my list. Sometimes we play symphonic repertoire such as the Brahms’ Haydn Variations or Shostakovich’s 9th Symphony. My colleagues in the wind section are the finest, and we have a great time together.

Three of the most important parts of having this job are projection, stamina, and consistency.

Projection: The Met Opera House is vast and cavernous. The pit has wonderful acoustics, but nevertheless, there is an imperative to play with a powerful sound that will fill up the hall. I find myself going into extra training before and during the ABT season, both with practicing and running.

Stamina: Ballets are long. Three acts require a lot of concentration and focus, not to mention physical endurance. Getting enough sleep, healthy meals, and exercise is crucial.

Consistency: We repeat each ballet eight times a week. This means you need to “hit it out of the park” consistently. I learned early on how to practice every solo so that I could replicate my ideal version over and over. Basically this meant playing the solo just as I wanted it and noticing exactly how it sounded and felt throughout my entire body. This imprinting is key for consistency.

Further Suggestions: Learn to be consistent. Be able to play excerpts over and over within a 5% margin of error. Learn some of the ballet repertoire just for fun. It will stretch your playing and you will be ahead of the game when you actually play it.

How did you get the Mannes position?

Back in 1989 Tom Nyfenger was the flute professor at Mannes and Yale. He took the Oberlin position and asked me to take his place at both Mannes and Yale, with him providing occasional team-teaching and guidance. I was young, and it was daunting at times, but I learned from his advice and by jumping straight into it. After Tom’s death, I was given the Mannes position, which became a central part of my life. As wind department chair, I have worked to create a strong program. I have eleven flute students this year and also coach chamber groups and teach flute class, wind class, and wind pedagogy. I oversee the progress and trajectories of all the wind players. When they graduate, I want them to be prepared and ready for the high standards of the professional music world.

What summer festivals do you attend?

Every June I travel to the Interlochen Flute Institute where I teach and perform with Nancy Stagnitta and Paula Robison. I also teach a session at the Aria International Summer Academy in Massachusetts. These festivals are often times of creative growth spurts for both students and teachers. I have also traveled to Taiwan for four summers for masterclass and recital tours as part of a festival created by a wonderful Taiwanese flutist who is a Mannes graduate.

What is your Practice Pyramid?

Bullet-proof technique and tone production are high priorities and set the stage for convincing musicianship. My Practice Pyramid is a template for how I see myself and all musicians. It is a pyramid with three layers: Solid Skills; Musical Intelligence; and Ideas, Imagination, Inspiration. In any college audition, I am looking for a player for whom I can check off all three layers.

Solid Skills: This refers to the foundation of tone, technique, rhythm, articulation, breath control, intonation.

Musical Intelligence: These are things one can see and hear, including composer, century, style, movement marking (Cantabile, Vivace), tempo, sequences, harmonies, cadences, phrase lengths, etc.

Ideas, Imagination, Inspiration: The tip of the pyramid is that element of magic, something like a hotline from the page to your heart.

My advice to students is to get the bottom two layers really solid. Then the magic tip will begin to flow naturally into your playing.

.jpg)

What is the number one deficiency in today’s conservatory students?

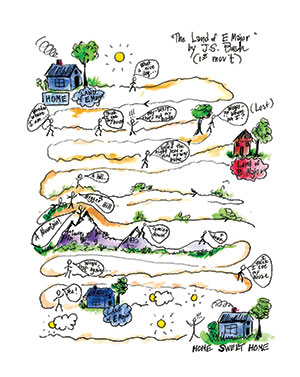

They ignore the second layer of the Practice Pyramid of musical intelligence. Their playing is disorganized and bland. I cannot tell what they want or what feeling and character they are trying to convey. They might have a good tone and technique, but they have not really looked at the page, listened, or planned. My mantra for them is to “always have a plan.” My students must organize and bring in a convincing interpretation – to the best of their abilities – to their lessons. To help them, I often give them a template like my cartoon map of the first movement of the J.S. Bach E Major Sonata (right), which shows a little guy walking through hills and mountains, and getting lost. The map follows the exact terrain of the music.

Another deficiency is that some students seem to think they can play the Brahms 4th excerpt without ever having listened to the complete movement or work. I tell them a complete musician knows the piano part and score. Never come into a lesson clueless about the other parts. This would be like learning the Juliet lines without knowing what Romeo is saying.

Another problem is when they come into lessons with problems they could have fixed at home with intelligent practicing. This is a waste of lesson time. I give them my handout of Creative Intelligent Practicing Strategies for fixing problems. I want them to have tools for solving tonal and technical problems on their own before lessons.

What do you focus on with first-year students?

• Developing a strong work ethic, work habits, and productivity; raising standards and confidence; setting goals; encouraging initiative, leadership, and curiosity.

• An etude per week from Andersen Op 33 or Berbiguier Etudes.

• Taffanel et Gaubert #4 scales, memorized.

• Three to four new orchestral excerpts per semester.

• Three to four pieces per semester such as: Hüe Fantaisie, Chaminade Concertino, Reinecke Concerto, Taffanel Andante Pastoral and Scherzettino, Burton Sonatina.

How do you teach melody?

• Sing the melody. This gives a natural flow.

• Put words to it and sing it. Language gives a natural shape and inflection, plus a sense of pickup/downbeat. The opening of Mozart G Major Concerto can be “You are my one true Sweet-heart!” The opening of the Widor Romance third movement, can be “I love you for-ev-er with all my heart.”

• I often put stars over the high points or hearts around the love notes on the music.

• A number system from 1-10 with 10 being the fullest works well with music such as the Franck Sonata first movement, where the flutist must be strategic about building the line.

• Color code the part. The first page of the Martin Ballade is basically turning smoke into electricity over 43 bars. Color the beginning gray/blue, the middle purple, the end bright, screaming red. Colors get a quicker response than p and mf markings.

• Moyse’s Tone Development Through Interpretation.

What do you practice to maintain consistency?

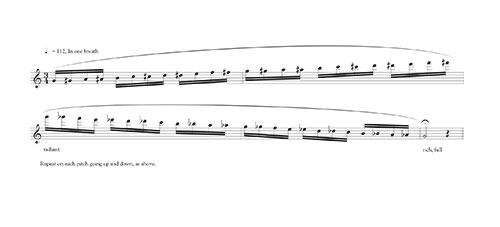

I have a daily warmup packet called Flute Gym made up of various exercises by which I swear, most of which are for tonal beauty, resonance, and power. I like to start by getting lips, air, and fingers working together with one- and two-octave chromatic scales up and down with a metronome. The high note should be open and full. Build the air speed several notes before top. The last, low note should be stable and rich. Elongate the penultimate note to ensure a good touchdown – much as a pilot would make sure the wheels are down before landing the plane. Harmonics and vibrato exercises are also a part of my daily routine. I love doing tone exercises from Bernold’s Vocalises and from Paul Edmund Davies’ The 28 Day Warm-Up Book. Of course, I also work on Taffanel et Gaubert No. 4 scales – four major/minor pairs per day, slurred and tongued.

How do you create your colorful sound?

I am a zealot for exercise and being in good physical shape; for me it’s a combination of running, yoga, and swimming. I want to be grounded, tension-free, aligned. A colorful sound begins with good posture and core strength.

• First, stand tall, head tall, chest up, rib cage lifted, shoulders and elbows relaxed and down. Power up your diaphragm (support). Resonance comes with being open: think three balloons in your chest, three eggs in your mouth (tongue down), and open your throat (think of yawning).

• For proper placement of the flute, rest the flute comfortably in the crook of the chin, lower lip resting fully on the lip plate. The flute should be optimally down on your lip. Lowering the flute a bit means a deeper angle of the air and more overtones. Lowering can give instant color, depth, and flexibility. It also means there is now more lower lip available on top of the lip plate which is a great resource for shaping the air stream. The lowering can be the slightest amount – it may not even be visible. Each person is different. Your ears will judge, and for some people, it is not necessary at all.

• Cover 1/3 to 2/3 of the embouchure hole with your lower lip. Depending on dynamic and register, there should be about 1/3 of the hole open at all times. Sometimes micro rolling out can open up the sound immediately. Lower jaw should be back and down. Blow down. Upper lip will be slightly canopied over the hole. Lips are juicy, flexible, and forward, guiding the air. Control and focus can come by anchoring down the corners of the mouth. There should be no undue pressure of the lip plate against the lip. Think of spinning the air all the way down to the foot joint and getting the tube to vibrate.

Do you have any hobbies to keep stress at bay?

Running, yoga and swimming are my daily practices. I go to a tiny island in Greece every summer where I hike, swim in the Aegean, and paint with watercolors. The freedom and fun of putting colors on paper, not knowing what will emerge, is deeply satisfying. It is a foil for the rigor of being a classical musician.

Judith Mendenhall has appeared throughout Europe, Asia, and the US as soloist, orchestral musician, chamber musician, and pedagogue. She has been presented in thirteen nationwide “Musicians From Marlboro” tours, has been guest artist with the Cleveland, Concord, Emerson, and Mendelssohn String Quartets, has been an assisting artist at the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, was a founding member of the Naumburg award-winning Aulos Wind Quintet, and a founding member of the Music Today ensemble. She has been principal flute of the New York Chamber Symphony under Gerard Schwarz, the Mostly Mozart Festival, the Grand Teton Music Festival, and the Colorado Music Festival.

Currently flute professor and chair of the wind department at the Mannes School of Music, she received the 2016 Distinguished Teaching Award from The New School University and is a faculty member at Queens College. Her summer festivals include the Interlochen Flute Institute, the Aria Summer Music Academy, and biannual recital and master class tours to Taiwan. She has recorded for Delos, Columbia, Vox, CRI, Koch, Bridge Records, and the Marlboro Recording Society.