Helen Blackburn regularly travels 350 miles between Canyon and Dallas, Texas. She is the flute professor at West Texas A&M and the principal flutist with the Dallas Opera. She is known for her lively and inspired teaching and performing.

How do you manage such a demanding schedule?

When I accepted the position at West Texas A&M University (WTAMU) in Canyon, a small town just south of Amarillo, I knew I wanted to feel settled there. I bought a house there rather than live in an apartment surrounded by students. My husband, percussionist Drew Lang, and one of our dogs live in Dallas, while I reside in Canyon with our other two dogs. It was important to have dogs with me in Canyon as a sort of anchor and also to provide some balance in my life. They force me to take long walks and not just live at the music school. I usually fly back and forth unless I am going to be in Dallas for an extended period, in which case I drive so the dogs can travel with me.

Commuting can be complicated. This year I have 23 flute majors at WTAMU plus several private students in both locations. When the opera season revs up and I add rehearsals, performances, and travel to my calendar, it becomes a real puzzle. My schedule is often drastically different from one week to the next. For example, if I have no opera services, I will be in Canyon all week teaching all day each day; but when we are rehearsing and performing two operas in repertory, I may fly back and forth between Dallas and Canyon two or three times a week.

During these weeks, I modify my schedule and teach small group lessons and also bring in a guest teacher for private lessons. I select guest teachers with diverse backgrounds who can share real-life experiences and give practical advice to my university students. This fall our guest teachers included an orchestral flutist who has a large private studio, a band director who plays flute, an orchestral flutist who is also a music therapist, and an elementary music teacher who is an excellent flutist. My students get the benefit of new teaching perspectives, but still have the consistency of weekly lessons with me.

I do not have a regimented personal practice schedule as it is just impossible. I manage to stay in good playing shape by warming up with my students and demonstrating or modeling during lessons. I have always learned music quickly and am efficient in my practice. I do a lot of mental practice on the airplane or when I walk with my dogs, but I go into practice overdrive mode if I have a recital or a tough piece looming on the horizon. Fortunately, I usually have so many performances on my calendar that I never fall too far off the practice wagon.

How do you prepare middle and high school flutists for collegiate study?

My primary goal is to instill in each student – no matter the age – an enduring love of music, along with strong fundamentals and problem solving methods. I find it impossible to teach music if the student is in disrepair. Ask any student who has had even one lesson with me, and they will say we start at the very beginning and go from there. To that end, I emphasize good posture and playing position, hand position, breathing, flexible embouchure, characteristic tone and vibrato, double and triple tonguing, a secure grasp of rhythm and subdivision, and fundamentals of technique plus as much standard repertoire as possible. When a student has no underlying bad habits, we can focus on the art and joy of making music. For those considering majoring in music, I add as much technique work as they can handle which might include the Taffanel et Gaubert 17 Big Daily Exercises and Walfrid Kujala’s Vade Mecum, orchestral excerpts, and more repertoire.

What is your core curriculum for a performance or music education major for the BM program?

My first objective is to rid students of bad habits they may have when they enter college and help them grow as much as possible in the four or five years they are in school. Of course I focus on fundamentals and standard repertoire, but I also put an emphasis on flute pedagogy. To paraphrase a dear friend, I don’t want my students to infect the next generation with the bad habits they may have had when they were younger.

What are your warmup and maintenance practice techniques?

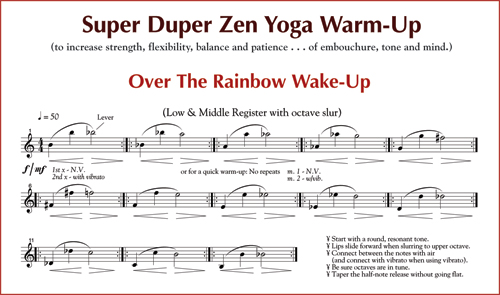

When I was younger and had time to spare, I had an extensive warm-up routine that took two to three hours daily. Sally Turk, my brilliant teacher, laughed and told me there was no way I could maintain that routine in life in the real world. I eventually distilled my favorite, most efficient, and most effective exercises into what I call my Super Duper Zen Yoga Warmups (see example below). The first five of these exercises take approximately seven minutes from start to finish and are the core of my playing and teaching. I start every day with them and find I can maintain embouchure strength, flexibility, and suppleness in this short time. Then I might rip through major and minor scales and arpeggios with different articulation patterns or favorite exercises from Taffanel et Gaubert or another technique book. That has to do it on most days. I am absolutely mad about technical studies and own almost every method book ever published. When I have more time, I love to rotate through them all.

What makes a beautiful tone?

I do not think there is one beautiful tone that should be applied to all music, but there is a characteristic tone for each instrument. This is something I refer to as First Chair of the Universe tone. This is the sound you would want to use if you were auditioning for First Chair of the Universe on just one note. When describing this tone, I would say it has core, depth, color, a balance of low and high partials, freedom, complexity, and zing. Having said that, it is important to be able to change sound, color, and dynamics to match the piece rather than imposing one sound on all pieces. This is why embouchure flexibility is important, but most important is having an explicit idea of the sound you are intending to produce. If you do not hear it inside your head before you play, what comes out your instrument could be anything.

Do you have any tips about articulation?

The tongue can and should be trained for speed and endurance just as an athlete trains for a marathon. However, the real purpose of articulation is to enunciate and clarify the musical line. I find many students ignore the printed articulation or do not tongue firmly enough for it to be heard. I think of articulation in many different ways depending on the piece. It can help to think of the bow stroke of a fine string player, the key stroke of a great pianist, the enunciation of a singer, or even the movement of a dancer.

What advice do you offer for flutists auditioning for a competition or college entrance?

A solo or concerto competition and a college entrance audition are two very different creatures. I did not enter a lot of competitions when I was young, and I do not encourage students to enter formal competitions until they have rid themselves of all bad habits and have solid fundamentals. Otherwise it seems that they reinforce bad habits while working toward the external goal of the competition. When I did enter competitions, I enjoyed working toward a goal and learning about myself from the experience. (I learned I’m a terrible procrastinator especially when it comes to memorizing pieces.) I feel fortunate that Sally Turk, my undergraduate teacher, put emphasis on becoming a better musician rather than on winning competitions.

Regarding college auditions, some teachers look for a near-finished, highly polished student while others consider the teachability of the flutist, attitude, personality and potential. Students should focus on fundamentals such as tone, rhythm, and technique, and choose repertoire that shows their strengths and allow them to be expressive rather than trying to impress with flashy, too difficult pieces. I encourage students to have at least one trial lesson with a teacher to see if they are a good fit for one another. There is no such thing as one perfect teacher for every student.

Do you encourage students to double major?

WTAMU offers degrees in music education, performance, music therapy, and business. Most of the students major in music education, with only a small number of students in the other concentrations. I am honest with my students about the difficulty of a career in performance and strongly encourage performance majors to consider a double major in music education or music business to give them more options.

As a flutist who plays both opera and symphonic literature, do the skills for each differ much?

Opera musicians have to play much more softly and be more sensitive to the conductor than when playing in a symphony orchestra. However, the skills required are essentially the same whether playing in an opera, symphony orchestra, solo, or chamber music setting. Good musicians are aware of their role in the musical context of the moment. It is necessary to play more soloistically when you have a prominent line and to blend into the texture when your voice is secondary. This means that you should have great flexibility with tone, color, vibrato, dynamics and articulation. One of my pet peeves is a flutist who plays everything with one sound, one vibrato, and one dynamic.

As a graduate of West Texas, what is it like to teach in the place where you studied?

It is a little surreal, but also completely natural to be teaching at WT after a 30-year hiatus from the Texas panhandle. When I graduated in 1982 and headed to Chicago for grad school, I thought I would never go back to Texas. Looking back on the progression of my life, however, I feel that every experience has led me back to WTAMU. I love the people of the panhandle and have a real bond with the students who are drawn to WTAMU. I share a common background with many of my students and almost feel as if I am repaying a karmic debt to help them achieve everything they dream of in their musical pursuits.

.jpg)

What sparked your interest in the flute?

I grew up in Dalhart, Texas (population 5,000) which is in the far northwest corner of the Texas panhandle. My mother was a veterinarian and my dad was a cowboy. Our family listened to country-western music (Patsy Cline, Johnny Cash, Tammy Wynette), rode horses every day, and participated in rodeos all summer. I was a barrel racer, carried our flag in the grand entry, and sometimes sang the national anthem.

The local band director was a charismatic man named Jack King. Everybody wanted to be in band. When it came time to choose an instrument in 5th grade, I ended up with the flute because it was the only instrument left in the want ads in the newspaper. I still remember the musty smell when I first opened the case and also remember thinking, “I guess I’m not going to be an English teacher after all. I’m going to play the flute!” Of course, I had no idea what that meant.

Since Dalhart was so far from civilization, I was unable to take private lessons. However, Nancy Chisum, a wonderful pianist who played for every event in Dalhart, practically adopted me. Every day for six years, I rode the school bus to her home. I sat next to her on the piano bench as she learned her accompaniment parts. She taught me bass clef and how to transpose. Nancy arranged for us to perform someplace almost every week. We played at every church in town, for the Rotary and Lions Clubs, the old folks home, and once we had finished that circuit, we did it again. By the time I got to college, I had had tons of performing experiences.

Though my parents had no musical background, they did everything possible to support me. They sent me to band camp every summer. My mother launched a search for a flute teacher and arranged for me to have random lessons when we traveled. When I was in the 10th grade, my mother drove me 105 miles each way to study with Brad Garner, who was a sophomore music major at West Texas State University. Though lessons were a bit sporadic because of the distance, Garner inspired me, got rid of bad habits, and gave me a good technical foundation.

In college I studied with Sally Turk at West Texas and then went to Northwestern with Walfrid Kujala for my master’s degree. I was lucky to have studied with this trio of teachers in the order that I did. Garner taught me how to play the flute correctly. Turk showed me how to play with relaxation and play on a high musical level with great detail and nuance. With Kujala I learned to be analytical and even more detail-oriented. It was a perfect triumvirate of three very different, but highly complementary teachers.

Why is it important for students to attend summer music festivals?

I did not attend a summer festival until several years after graduate school when I sent in a recording for the piccolo fellowship at Aspen and got the spot. I played in Aspen for four summers, and it was one of the best experiences of my life. I was surrounded by amazing musicians and had to learn music really quickly because we gave a full orchestra concert every week. (We played almost every huge piccolo piece my first summer: Shostakovich 6, Bartok Concerto for Orchestra, Scheherazade, Beethoven 9, Daphnis, etc.) So much fun!

What type of repertoire do you program for your flute and marimba duo with your husband Drew Lang?

We do not have much time these days for exploring new repertoire because we both seem to always have a million projects on our plates, but our two favorite pieces are Gareth Farr’s Kembang Suling and Drew’s transcription of Robert Beaser’s Mountain Songs which were originally for flute and guitar. We have commissioned a few pieces, including Rhapsodia by Bradley Bodine. We will adapt anything that interests us including works by Bach, Jake Heggie’s Soliloquy, Ian Clarke’s Hypnosis, Irish reels, and jazz charts.

What were your other teaching experiences before coming to West Texas?

I have definitely had myriad experiences and paid my dues, though I never applied for a teaching job in my life except for my current position at WT. Immediately after graduate school I was recruited by friends to move to Midland, Texas where I taught 96 students each week and played third flute and piccolo in the Midland/Odessa Symphony. After two years in Midland, I was offered a job teaching part-time at McMurry College in Abilene. This soon became a full-time position in which I taught all applied woodwinds, sophomore theory, elementary music education, woodwind methods, played clarinet in band, played baritone saxophone in the jazz band, and was coerced into being a flag girl in marching band. I also taught approximately 50 private students on the side in order to pay my bills. I also met my husband at McMurry.

After three years at McMurry I accepted a part-time position at Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches, where I was strictly the flute professor (aside from a brief stint as color guard coordinator and one semester of teaching a music appreciation class) and built the studio up to a full-time position. I still taught about 40 private students in addition to my university load.

I never really did many orchestral auditions for several reasons: it was so expensive to audition; I loathed practicing excerpts for years on end; and I did not like the emotional fall out. However, while at SFA I took an audition for principal flute of the Dallas Opera to serve as an example to my students. I thought if I prepared well, played all the excerpts for my students (so they knew I was ready), and then auditioned and did not get the job, they would get an idea of how competitive it is in the orchestral world. I had no emotional investment in winning this audition and really could not take the job if I won because I had a full-time job at SFA three hours away. Life is strange though, because I won the audition and then had to figure out how to make it work. For two years I led a hectic life driving back and forth the 180 miles between Dallas and Nacogdoches before resigning my position at SFA.

Next I taught at Texas Christian University for 12 years as an adjunct professor and concurrently part-time at the University of North Texas for six years. I am now in my fourth year at WTAMU in a full-time position. The obvious benefits of having a full-time position are being in charge of the direction of the flute studio and a better salary and benefits. The drawback is meetings! Fortunately, the director of the School of Music at WTAMU is wonderful, and full faculty meetings are few and far between.

If you weren’t playing and teaching, what would you be doing?

Many times through my early career I questioned if I was really doing the right thing with my life. I think this is fairly common among musicians because we work really hard and spend a lot of time practicing alone with little recognition or financial reward. In my twenties I considered following my siblings’ paths (geophysicist and attorney) or just finding a career that was not in music. I always came back to the realization that I was doing exactly what I was put on this planet to do: teach and perform.

I would be incomplete if I only did one without the other, but I have learned that I do need to take breaks from both in order to stay fresh. There was a period of many years that I taught every single day of the year including Christmas and Thanksgiving. I finally learned that I need to allow time to replenish my soul. I honestly cannot imagine myself doing anything other than what I’m doing. Well, maybe I could be a professional dog walker.

Helen Blackburn is the Yvonne Franklin Endowed Chair Artist Teacher of Flute at West Texas A&M University (WTAMU) in Canyon, Texas. She is also principal flute of the Dallas Opera Orchestra, a core member of the modern chamber music ensemble Voices of Change, principal flute of the Breckenridge Music Festival and founder/director of The Big Fat Flute Shindig at WTAMU. She has been a prize winner of the Myrna W. Brown Artist Competition, the Fort Collins Young Artist Competition, and the Aspen Wind Concerto Competition. Blackburn previously served on the faculties of Texas Christian University, University of North Texas, Stephen F. Austin State University and McMurry University. She is a graduate of West Texas State University (BM – Sally Turk) and Northwestern University (MM – Walfrid Kujala).