When I audition students, the sightreading excerpt I choose is usually written in three and in a minor key. Afterwards the flutist usually apologizes for his poor playing of this excerpt saying, “It looks so simple on the page.” However, within a phrase of eight measures or just a few seconds, I glean a lot of information about how this flutist will function in an orchestra. Why I select an excerpt in a minor key is obvious, as the ones who know all their scales will know the minor keys, but the choice of a selection in three may seem less clear.

Students struggle with learning and performing pieces that are written in three. One reason is a simple lack of exposure to meters based on threes whether it is a simple meter of 3/4 or the compound meter of 9/8. Playing in three also does not feel natural for us because our bodies are built in two. We have two legs so we walk left and then right. We open and close our eyes. We breathe in and out. Even the heart beats in pulses in two. For this reason, understanding and playing in two is much more natural than playing in three. Many beginning books omit the 3/4 time signature until later in the school year.

When students struggle in the sightreading portion of an audition with an excerpt in three, I know they are not really counting but are just feeling the pulse. When the pulse is an unknown or awkward one (in other words, not in the comfortable and predictable two or four), they make mistakes. To function well in orchestra, musicians must be able to count independently.

In talking with some of our most gifted players today, they recall sightreading lessons with their mentor in which the slow movements of the Kuhlau Duos were read. Almost every one relates that humiliating moment when they were soaring through the allegro movements, but died a slow death in the mis-counting of the slow movements, many of which are in subdivided three. Mastering these slow movements is one of the keys to survival in playing the slow movements of most Classic and Romantic symphonies.

Three Choices of Tempo

If playing in three at a fast tempo, the conductor will conduct in a beat pattern of one, taking a complete measure in one gesture. This conducting pattern will often offer a hint of where beats two and three are. The accent or inflection is on the first beat. If the tempo is quite slow, then the conductor will subdivide the beats 1+, 2+, 3+. In this tempo, the first beat is strong, the second less strong, and the third is weak. However, if the tempo is moderate all three beats will be conducted.

The Long Notes

One of the first problems students encounter in playing in three is the long notes. In 3/4 the long note (one that fills a measure) is the dotted half-note. Often students will play the long note through three and then linger another beat where the fourth beat would be in 4/4 meter because they are unused to the asymmetrical nature of the measure. Counting aloud while a student plays or making up words (Here we go; Step, tip, toe) may solve this problem.

Teaching the Waltz

In the Baroque, the meters of four beats ( 4/2 , c=common time, 12/4 , 12/8 , and 12/16) and two beats (C, 2/1, 2/4, 2/8, 2/16, 6/4, 6/8) were commonly used; however, meters of three offered fewer options (3/1, 3/2, 3/4, 3/8). This may be because music of the Baroque was primarily used for dancing and since we have two feet, the meters in two or four beats were simply easier to dance to than meters in three. Of course over time, all of the early Baroque dances became stylized and were intended more for listening rather than dancing so writing in three became more common. Compositions of the Baroque period that were written in three included lullabies, plaints, graves, courantes, passacaglias, chaconnes, sarabands, and minuets among others.

Teaching students how to waltz is a challenge in itself because to do this correctly the patterning of the feet is left, right, left and then right, left, right. This alternation is confusing to many and will have to be drilled until they can visualize this alternation. Unlike many dances (or moves in marching band, where the feet move alternately left, right), learning to alternate the leading foot can be a challenge. While waltzing, I first have students say, “Right, left, right. Left, right, left” a few times to be sure they have the idea before moving their feet. Then once they have the idea, have them say: “Step, tip, toe.” The helps the student learn to inflect the beats properly for 3/4, where the first beat is strong, the next less strong, and the three is weak.

Scanning Poetry

When many of us were in grade school, we studied poetry. This may or may not be in the curriculum for students today. We scanned the poem and looked for meter, stanza, and rhyme scheme. When scanning for meter, we read aloud listening for which syllables were stressed and which were unstressed. There was a short hand (a line for a long or stressed syllable and a u for a short or unstressed syllable) to indicate what we had found. These patterns of stressed and unstressed syllables were in rhythmic patterns called meters with names such as anapest, dactyl, iambic, and trochee. These same words are implied in music too.

In the music of the 1200s the need for some kind of way of notating rhythms became apparent. Composers of the period notated and classified rhythms and patterns into what they called modes. There were six rhythmic modes which were each referred to by number. These modes were based on the values of long and short similar to those in poetry. Mode 1 (half note followed by a quarter) was a long and a short which is the poetic equivalent to the trochaic. Mode 2 (quarter followed by a half note) was a short and a long which is the poetic iambic and so forth.

While many dances employ a half note followed by a quarter note or the opposite in many measures, composers began to fill in other notes over this skeleton. If students learn to recognize this organizational technique, then their reading and performance will be more fluid. Note the placement of the brackets to indicate whether the half-note/quarter or a quarter-note/half is implied. Of course, there is no right or wrong way to bracket notes. Each person may see the patterning in a different way, but the important rule to follow is to have a way.

Joachim Andersen, Op. 21, No. 1

.jpg)

In Jacques Castédède’s Douze Etudes pour Flute, No. VI, he uses the same technique. Notice that the arpeggio on beats 2 and 3 are spelled the same.

Castédède Douze Etudes, No. VI

.jpg)

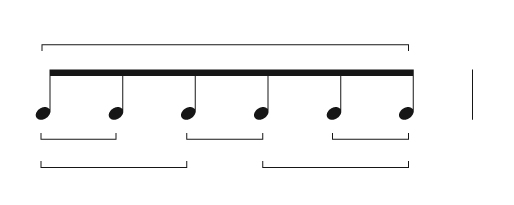

Note-Grouping

At the top of my copy of Joachim Andersen’s 30 Instructive Studies for Flute, Op. 30, No. 2 in A minor, William Kincaid wrote the following note-grouping marks for examples when there were six eighth-notes per measure in 34 time. He said that version A was the most common, and I was to also use it in the technical patterns in the 17 Big Daily Exercises by Taffanel & Gaubert No. 6, 11, and 13. He said I would find a use for version B in playing Baroque music, and version 3 would be used when the tempo was quite brisk. Over the years I have found that there are several other possibilities that work well in both early and contemporary music. My suggestion is that for each passage you encounter, try one of the grouping patterns and figure out which produces the best results for you. There is no single answer.

.jpg)

Practicing in Three

For advanced players, practicing scales in three can help them develop their technique. When playing scales in three, the accented note is different from playing scales by four or eight notes. Learning to accept this accenting will even the fingers so the technique is equally strong whether in two or in three.

.jpg)

Playing well in three is a skill that must be understood and practiced, but the good news is that some of the most wonderful music written is in three.

* * *

Elements of Time: Tempo and Meter

Tempo (Speed)

Tempo (Italian for time, plural tempi) instructions were first indicated in the early Baroque period (1600-1750). Since the preeminent composers of the day were Italian, they used their native language to convey the speed of the composition. Common terms were: grave, lento, largo, adagio, andante, moderato, allegro, vivace, and presto. Composers from other locations followed suit continuing the use of the Italian language.

However, during the Classic and Romantic periods, other words were added to the tempo to indicate the mood of the composition. These words might include meno (less), piu (more), and poco (a little) for example.

With the rise of Nationalism in the late 19th century, composers began to write tempo instructions in their native tongues. This is why we see tempo markings in many languages including Russian, German, French, and English. On concert programs, tempo markings are often used to identify a movement in a multi-movement piece or may be the title for a standalone one-movement composition.

In the early 1800s the metro-nome was invented and many composers also specified their tempo instructions with the marking M.M = 60. The M.M. stood for Maelzel’s Metronome; however, we now know that Maelzel patented the work of another inventor and named the invention after himself.

In the 1980s the quartz metronome replaced the original spring, windup metronomes offering a more accurate indication of the tempo. With a quartz metronome musicians could increase the tempo in increments of one beat per minute (BPM) from 40 to 250 or more. This was a marked improvement over older windup metronomes that moved up from 40 BPM by in increments of two, three, four, and six.

Meter (Grouping of Pulses)

If you tap along with a metronome and then begin accenting every other beat, your mind has grouped the ticks by twos. A similar grouping occurs if you accent by threes or fours. In everyday life this is apparent when listening to a grandfather pendulum-type clock. We hear tick-tock rather than tick-tick.

To illustrate the meter of a composition a time signature comprised of two numbers is printed at the beginning of the piece. The top number indicates how many beats there will be in a measure, and the bottom number represents what type of note (half, quarter, eighth, or sixteenth) receives one beat. Barlines are placed to mark off the piece into measures. Each measure will contain the number of beats indicated in the top number of the time signature.

Meter may be simple or compound. If the beat is divisible by 2, then it is called simple meter. Those that are divisible by three are called compound meters.