While music theory is an important part of a flutist’s formal training, it is often neglected in private lessons. There are always so many other things to think about: tone, double tonguing, all-state audition music, solo and ensemble festival competitions. However, music theory does not have to be time consuming or complicated; it can even be fun. Any time given to it will be time well spent.

Ask Questions

With simple questions during a lesson, a teacher can quickly discover what a student does and does not know. As you introduce a new piece, ask what the key is. If the student does not know, look at the music together and point out that music usually ends on the tonic. For a piece in a minor key, ask the student to name the leading tone and find several examples in the music. If the work changes keys in the middle, ask what the new key is and how it relates to the original key. Student pieces often modulate to the relative major or minor, and usually modulate to the dominant key. With your help, students can mark phrases and find basic forms. Even young students can learn to recognize ABA form. More advanced students can answer questions about triads (major vs. minor or identifying I, IV, V triads in a key) and intervals.

Theoretical Terminology

Teach students important terms by using the terms consistently in lessons. These terms include tonic, dominant, interval names (such as perfect fifth), meter, cadence, enharmonic, etc. Most students will never notice as you prepare their minds for music theory studies.

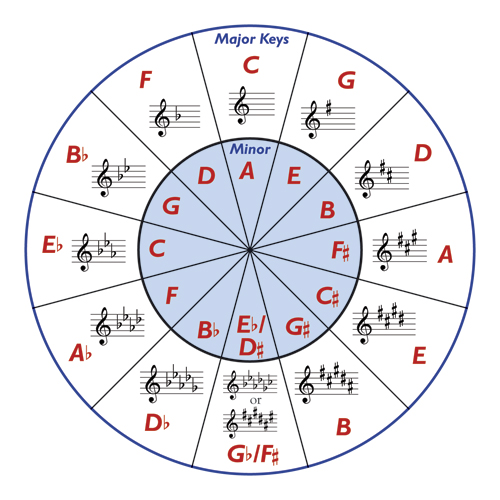

The Circle of Fifths

The circle of fifths is one of the greatest teaching tools because it relates to so many aspects of music theory: scales, key signatures, the order of flats and sharps, intervals, chord progressions, and modulation. An easy introduction is to teach scales with the chart rather than a traditional scale sheet. Even young students can have great success with this (and they often complain less because they assume it is the norm). If a student is not used to this method, begin with C major. Have the student spell the scale aloud – C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C. Point out that each letter is used once, you never have two of the same letter used next to each other. Then have the student spell the next scale on the circle of fifths. This could be either G major or F major depending on which direction you prefer. Students should spell the scale alphabetically first without sharps or flats and then again with the key signature listed on the circle of fifths chart. (pdf)

Play by Ear

Flutists who play by ear generally listen more acutely than those who do not develop this skill. It also aids memorization, improvisation, and intonation. If a student continues his music studies in college, the ability to play be ear provides a background for aural skills dictation exercises and for jazz studies.

Have the student select one song a week to play by ear. Begin with the standards: Twinkle Twinkle, Mary Had a Little Lamb, Happy Birthday, or the Star-Spangled Banner. Pop songs are often a favored alternative.

Ask students to play from memory part of the weekly lesson assignment that has not been officially memorized. It may be a bit rough, but students should be able to figure out a phrase or two.

Play the Echo Game

A great way to begin or end a lesson is the Echo Game. Play a short melody, or even a 3-note motive, and ask students to play it back. This game is difficult for shy students and those who are used to excelling at everything. It may take a while before students develop this skill. Simple, triadic melodies are good initial choices. Variations may include interval and rhythmic practice. For example, choose an interval for the week. A minor third is a good place to start as it is the interval young children chant on the playground. Introduce songs based on the various intervals to help students hear the distance – Twinkle, for the ascending perfect fifth or Here Comes the Bride for the ascending perfect fourth.

For rhythmic practice, play a rhythm using the metronome, and have students play it back. Occasionally, rather than playing the rhythm, have students count it aloud (1, 2 +, 3+, 4).

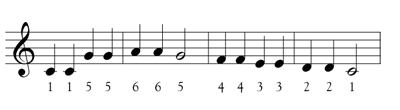

Interval Practice and Daily Warm-up

Pick a starting note and descend by the chosen interval.

.jpg)

The exercise becomes rather short with large intervals, so another option is to start on the first pitch and descend a perfect fifth, for example. Then begin one half-step lower, continuing the pattern.

Once the exercise is completed in the lower register, repeat ascending.

This exercise requires mental focus to remember which note comes next and serves as an aid for learning intonation between intervals. Practice with a tuner.

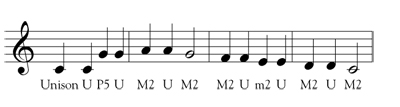

Transpose

Transposition exercises are essential for ear training and awareness of which degree or scale step a melody uses. Start students with simple melodies so they can transpose using their theory skills, and not just by listening or guessing. There are several ways to teach transposition.

1.Solfeggio

2.Numbers (works well with students who have had piano training)

3.Scale degrees

.jpg)

4.Intervals from one note to the next

Encourage Composition

Composition is the equivalent of teaching a child to write as well as read. When students learn to compose melodies, they develop a better understanding of basic elements of music theory, such as key signatures, time signatures, and scales. Provide staff paper for this assignment. To get started, have students follow these steps.

1. Write the key signature and time signature of the piece.

2. Place bar lines for 4 measures.

3. Bar 1: The first note of the piece is the tonic or first note of the scale.

4. Bars 1-3: After the tonic note, use pitches from the scale in a variety of rhythms. Each measure should include the proper number of beats.

5. Bar 4: End on the tonic note.

6. Play your piece.

After completing this assignment, students can expand upon these concepts. For example, on the melody notes, use accidentals outside the key signature. Make the piece longer by repeating some of the material. Modulate in the middle. Explore the use of sequential figures, broken chords, triplets, trills, repeats or D.C. al fine. Remember to include performance, dynamic, and articulation marks. Eventually students should write a duet.

Conducting

Students will learn to feel the meter through conducting. It also helps with ear training and memorization, as it is much easier to mentally organize a piece when you feel the meter. Before a student can conduct, he must be able to feel the beat. Practice finding the beat with various songs at different tempos. This may take some students a few weeks to master. Then have students conduct as you play a song. (Examples of conducting beat patterns are available online.) Start with music that does not change time signatures. Learn a new meter each month. Once standard basic conducting patterns are learned, conduct a pop tune together. Then, if the song is in 44 time, try to conduct it in 34 and show the student how the strong beats in the music do not line up with the conducted downbeats. The student should be able to tell that something does not feel right. Students should then try to figure out the correct meter of pieces. Assign two or three pieces a week to explore these ideas.

Computer Games

Children love computer games. If you purchase a music theory program and have access to a computer in your studio, a student can spend 15-30 minutes of computer time following his lesson while you teach the next student. Many parents consider this a bonus; you might consider charging a small computer fee to pay for the program. Their are also some free theory lessons online that may be suitable for your students.

Theory Workbooks

With music theory workbooks teachers can monitor students’ understanding of concepts. It is a way of making sure that all topics are covered and provides a useful resource for future reference. Pianists begin their studies with theory workbooks, and flutists should too.

As you incorporate a music theory curriculum into lessons, pick one or two of the ideas first. Then with time, move on to others. You will be surprised how quickly students improve, not only with their theory skills, but in their flute performances.