Drumline instruction can be a special challenge for any teacher lacking a background in marching percussion. Here are some tips to improve your percussion students’ musicianship, address common technical concerns, and develop a strong ensemble sound that supports your band.

Warmups

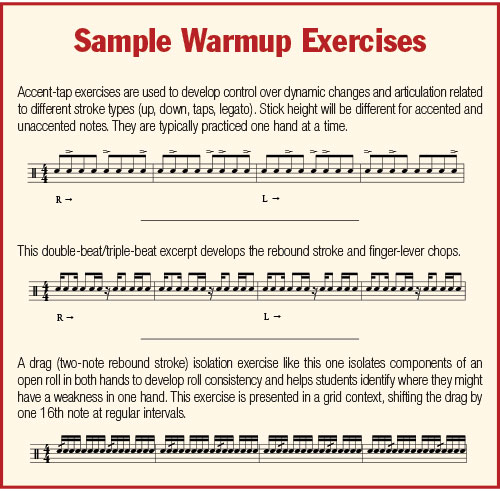

Keep your drumline’s warmup music straightforward, fairly easy to learn, pattern based, and brief. Make sure warmups are focused on the techniques needed to play the show. The best exercises that will warm up the player physically and develop skills over the long term are legato strokes, accent-tap patterns, 16th-note and eighth-note-triplet accent patterns, rhythmic timing patterns (especially some that include rests), double-strokes, diddle and drag isolation, and rolls. Intermediate programs should add flam and paradiddle exercises as well. I like a straightforward and brief warmup because students will be able to memorize it. It is good to work on reading, but students must also focus on developing good technique and listening within the section.

Beware of percussionists becoming too comfortable with their warmup set. Typically students play the same warmup all season long – and sometimes year to year. I like to change warmups slightly each year so that there is something new that students have to read. I don’t just dictate it to them; I put sheet music in front of them.

Reading and Listening

Encourage the development of reading skills during marching season. If a marching program focuses on one show for the entire season, that can unintentionally undercut reading skills. Students learn the show in the early parts of the season, but after the music is learned, rehearsals are mostly repetition. The problem is compounded if rote teaching is used as a shortcut to learn music.

I like to sightread music at the beginning of every rehearsal. This can be more difficult with younger students, but it is in the early years that sightreading is most needed to instill better reading habits. The aim is for students to recognize the vocabulary of the notation in front of them and translate that to performance.

Before students have their marching music memorized, make a habit of referring to the notation. Identify rudimental elements as they appear in the percussion parts to strengthen vocabulary recognition.

Most high school programs buy published arrangements for playing in the stands at football games, and I use that music heavily for sightreading. Focus on your drumline when playing these charts. Do not assume that the presence of a back beat and general sense of ensemble time means that all is well. In rehearsal, ask students to articulate rhythms to make sure they are counting correctly, and have the section come up with sticking patterns for difficult passages.

Teach students to understand the relationship between their part and the other drumline instruments. I like to show students the score and point out the rhythmic interplay of the parts. This way I can ask if they both hear it and see it. This transfers to both concert band and chamber music because it opens students’ ears to the other players. They move from simply playing at the same time and relying on feel to paying attention to the actual relationship between their parts. A snare drummer playing off the beat will think to lock in with a bass drummer playing on the beat.

Identifying Rudiments

If a program spends a great deal of time on marching, it is critical to make sure techniques and concepts transfer from marching season to concert season, as well as in the other direction, so you develop well-rounded musicians. Rudimental vocabulary has evolved as all language does, but the building blocks are the same. There are legato and natural strokes, upstrokes and downstrokes, rebound strokes, opened and closed rolls, paradiddles, ruffs, drags, and flams; after that point everything consists of patterns, combinations, permutations, and embellishments within the context of the music. Rudiments are a language, so you can talk about rudiments as words that are combined to form grammatically coherent sentences that are then combined to form artful paragraphs.

If you program a traditional American march for concert band, that is an opportunity to identify rudimental vocabulary. Help your students see that the flam accent in the march you programmed for concert season is no different than what appeared in their marching percussion book earlier in the year, except perhaps for the rhythmic subdivision or the style with which the passage is executed. They will become better readers and learn their repertoire more quickly.

Material in the Percussive Arts Society International Drum Rudiments will help students see the history of military drumming. Tracing the relationship between early military drumming and contemporary playing can be an interesting music history conversation with your students.

The crossover occurs in solo literature as well. Introduce students to the solos of Charles Wilcoxon and John S. Pratt. Their works contain a particular rudimental vocabulary and style that has evolved into what is used in modern marching percussion music, and there is a connection there that students can identify.

Fingers and Fulcrums

Sometimes percussionists play with a closed hand, keeping the third, fourth, and fifth fingers close on the stick even when trying to get a rebound stroke or stay relaxed at higher tempos. They have not developed proper use of the finger lever, and therefore the stick is not pivoting through the fulcrum, which is critical for many different elements of playing percussion. It is an essential part of a rebound stroke, opened and closed rolls, relaxed playing at higher tempi, and flams.

Any rudimental playing is going to require the player to understand how to open the back of the hand. This does not mean fingers off the stick and flayed out to the sides, which introduces tension to the top of the hand and the forearm. Fingers should be relaxed, with the palm acting as shock absorber for the back of the stick. Alternatively, when engaging the finger lever, they should be used as a contracting muscle into the palm to help support the stick.

Flams

Some students will also struggle to play flams in context. Students often learn to play a flam – or maybe consecutive alternating flams – in slower rhythms in grade 2 or 3 band literature, but flams in marching music are likely to come much more quickly. This requires an understanding of the relationship between not just the flam itself but the notes on either side of the flam, and how that affects playing the grace note. The Percussive Arts Society International Drum Rudiment #21: The Flam Accent can help to develop this basic skill. One great exercise for this is to focus on playing it at extremely slow tempos and work it up gradually, keeping both the unaccented notes low and the grace notes low. The body will learn how to integrate the relationship between the flam itself and the notes on either side of the flam. It is critical to practice this with both hands. As the speed increases and students get comfortable, they can stay loose while playing the flam, because they are used to seeing them as part of a phrase.

Dynamics

Define a playing height system and enforce it. One hallmark of a good marching percussion section is the ability to sound like one voice, and one way to do that is to unify the physics of motion across the section. Stick heights are an important part of that. We tie them to dynamics, using heights of 3", 6", 9", 12", and 15" for dynamics from piano to fortissimo, so when players see written dynamics they automatically play at a certain height. Setting a playing height is only useful in marching percussion, where three to seven snare drummers try to sound like one instrument. A percussionist assigned to play snare drum in concert band should play at the height that fits the music and allows for personal expression.

Some students may need help with stick and mallet height control, especially for sudden dynamic changes. If the part changes from forte to piano (subito), they will have to execute a controlled down stroke, which starts with the stick in a higher position and ends in a lower position (usually tap height). Students tend to implement the height change by tensing up to avoid an unwanted rebound, but the key to avoiding tension is to focus on the timing of the rebound prevention. Students should gently squeeze the fulcrum while closing the back of the hand to prevent the stick or mallet from coming back up. One phrase I like to use is “only as much tension as is required.” Rather than forcing the stick or mallet down, students are preventing it from coming back up. The end result might be the same, but the second approach requires less tension.

A sudden change from piano to forte takes a bit more work. The upstroke requires students to play a tap and then physically lift the stick or mallet, because there is not enough rebound force to overcome gravity without assistance.

For gradual dynamic changes, practice legato strokes that subtly change heights. This will give your students the control necessary for a smooth crescendo and diminuendo.

Marching Technique

Spend more time marching while playing something besides eighth notes in a warmup. Marching warmups typically include work going forward, backward, and sideways, maybe followed by a box drill. Then the band moves right to working on drill, which likely includes many different angles and odd changes of direction lined up against complicated music. There is a critical intermediate developmental step missing, and skipping it prevents students from mastering rhythmic phrases combined with direction changes.

I have students march an envelope drill:

.jpg)

Students march around the perimeter of the envelope and then make a diagonal change along the angled flap and back out. I have students play a cadence or some of the more difficult passages from the warmup while marching an envelope drill. This helps students understand the relationship between their feet and their hands. In their brain they develop much more integration of movement and playing than they would just marching forward and backward while playing eighth notes.

Resources

There are a host of publications for marching percussion development, and they usually fall into three categories: exercises and prior performance material from a notable DCI/WGI drumline program, method books that focus on specialized techniques and vocabulary, and collections of progressively graded exercises and etudes specifically designed for developmental and performance use in educational environments. Some of the well-known publishers of marching percussion education and performance material include Row-Loff (which now also owns the drop6 catalog), Tapspace, and The Grid Book Series.

There are two particular marching percussion developmental resources that I think are well-suited to assist beginning and intermediate high school drumlines (and their band directors). Vic Firth’s Marching Percussion 101 free online video guide is a great starting place for high school band directors who find themselves in charge of an inexperienced drumline. The Packet by Frank Chapple is a developmental percussion method book that is strong in marching percussion techniques and applications. It has useful material for beginning to intermediate levels of the activity, including sightreading exercises.

****

Instrumentation For Small Programs

Small programs should start with the bare bones; if you have one percussionist, he should march bass drum. With two percussionists, add a snare drum, and if there is a third, add cymbals. This combination gives your band everything it needs to handle the basics.

The next instrument to add is a second bass drum of a different pitch. Some programs use one big bass drum and add tenors sooner, but having multiple basses teaches students how to fit their split parts together to sound like one instrument. I follow a second bass with a second snare and a third bass. I do not consider adding tenors until there are at least two snares and three basses. That may seem arbitrary, and people can experiment with what works for them, but the most critical element of the drumline is a projecting bass voice that drives the ensemble on the field. The tenor voice is lovely. It develops multi-percussion skills and has excellent transfer value for other areas of percussion, but it does not help your band on the field the way a strong bass drumline can.

If possible, having a front ensemble is worthwhile, even if it consists of one marimba and one xylophone. It might be true that you don’t hear that one marimba or xylophone for much the marching show, but if you write parts in which they are the only instruments playing or include them in important woodwind passages, then you can get a wonderful change in tone color, which adds aesthetic interest to the show. There is also the benefit of improving keyboard technique in your percussion students. In a small program there might not be percussionists to spare. It is still worth teaching double reed players or even flute or clarinet players with piano experience how to play mallet percussion to add this tone color to the ensemble.