There are many famous quotes from classical composers concerning music notation and expressive phrasing. One of the more familiar statements comes from Gustav Mahler who, in the middle of a rehearsal, is said to have stated, “everything is in the written music but that which is essential.” Music notation has its limitations concerning indicating expressive phrasing and other subtle details of performing. In jazz, we often refer to the written music as charts, implying only an outline of how it is to be played.

When performing in an ensemble, if all players think alike in terms of the same sub-phrase groupings and apply the same expressive phrasing, the performance is exciting and interesting for both musicians and audience. This involves applying the natural inflection of the prevailing meter to the sub-phrases each moment.

Composers frequently write music that flows from weak to strong beats in the meter, creating a wave effect, as noted by Pablo Casals. When this wave effect is omitted, as is especially prone to happen when an ensemble is playing in meter-in-one, the result is a dull or uninteresting performance.

Two-beat meters have a strong-light pattern. In three, the pattern is strong-light-light, and in four it is strong-light-secondary strong-light. Light beats in a meter function either as a light expression following a strong beat or a light expression leading to the next strong beat. If there are two light beats in a row, each one may have a different role in the expressive phrasing sub-phrases.

The prevailing tempo should also be considered when working out detail in sub-phase groupings. What is musically noticeable at a slow or moderate tempo may not be at a fast tempo as it may be incorporated into a longer sub-phase. In many instances, there may be different sub-phrase groupings justified according to the such factors as prevailing contour, changes in direction, leaps and resolutions, rhythmic activity, tonality, and non-chord tones. The conductor must establish a common sub-phrase grouping so that the players think alike when performing within the natural inflection of the prevailing meter.

The following two excepts from Gustav Holst’s Suites in Eb and F demonstrate the natural sub-phrase groupings that occur when natural inflection of the weak and strong beats in the prevailing meter are considered and applied.

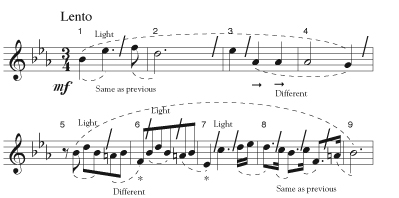

“Chaconne” from First Suite in Eb by Gustav Holst – beginning unison theme, as written:

First Suite in Eb and Second Suite in F by Gustav Holst copyright Boosey & Co. Ltd. Used with permission.

Played:

Notice that except for the cadence measures, every sub-phrase flows over the barline, creating the wave effect in a 3-1-2 beat grouping. The high tone in measure one is a light expression and a pick-up to the following downbeat. The half notes in measures one, two, four, and five should get a slight diminuendo so the sub-phrase continuation is noticeable. In the two-bar cadences in measures three-four and six-seven, the half note F acts as both a tone of resolution (from the C) and also a pick-up to the cadence tone Bb. The quarter note on the downbeat of measures three and six should be emphasized following the phrasing principle that tones of short duration on strong beats resolve to lighter, longer tones. Verbal directions to the ensemble would just ask for a 3-1-2 grouping over the barline.

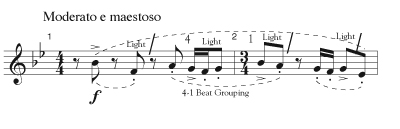

“Song of the Blacksmith” from Second Suite in F by Gustav Holst – beginning, as written:

Played:

The opening theme may be explained as being performed in three sub-phrases using a four-one beat grouping over the barline in the second sub-phrase. Accents have replaced the staccato markings on the important notes with accents to help indicate stylistic inflection. The second tone in first two measures should be played with less emphasis, which fits the natural inflection of the meter. The rests on the downbeats should be felt with the same emphasis as though a note were present following the natural strong and weak beat inflection of both meters. That puts the periodic emphasis on the concert Bb, first off the beat in measure one and then on the beat in measure two. Encourage the musicians playing second and third parts to play expressively even though their parts do not contain the same quality of contour as the lead part. When all the members of the brass section think in terms of the three sub-phrases and the natural inflection of the prevailing meters, the result is stunning at a forte dynamic.

Making Choices in Analyzing Melodies

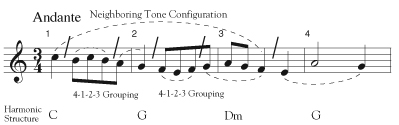

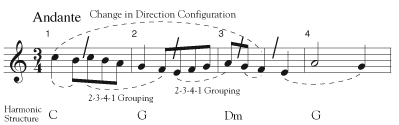

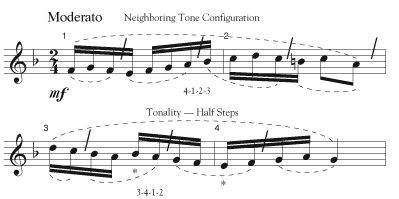

There are two different ways to perform the following musical phrase. Each one results in a slightly different expression in style, and both are valid according to the melodic content and desired style of the performance of the piece. Both solutions treat the eighth-note rhythmic activity of the weak beats (second and third) as moving over the barline from weak to strong, creating the wave effect, but use different sub-phrase groupings according to the contour of the line.

Written:

Played (option 1):

This first option recognizes the neighboring tone configuration and incorporates it into the sub-phrase grouping, using a 4-1-2-3 grouping of the four eighth notes.

Played (option 2):

A second possibility bases phrasing on changes in direction, creating a more flowing style with longer sub-phrases moving over the barline. It uses a 2-3-4-1 grouping of the four eighth-notes.

The conductor is responsible for establishing the expressive sub-phrases. In the above example, you may imagine how an ensemble would sound if some players base sub-phrases on neighboring tones, others on changes in direction, and a group of players only thinks note-to-note without any sub-phrase groupings or awareness of the natural inflections of the meter.

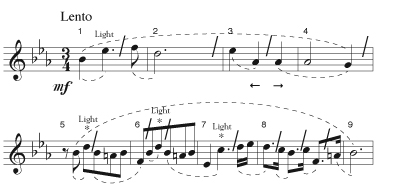

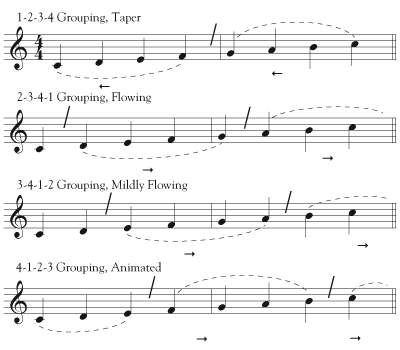

“Aria,” When Thou Art Near by J.S. Bach/Nowak. Opening melody scored for woodwinds in octaves with chordal accompaniment in a quarter-note harmonic rhythm. As written:

“Aria,” When Thou Art Near by J.S. Bach/Nowak, copyright Northeastern Music. Used with permission.

In measures one, five, six, and seven, the guiding principle should be that the leaps to weak beats in the meter are usually light. Measure three applies the repeated tone principle by placing the repeated Abs on weak beats in two different sub-phrases (noted by the arrows) in an animated Baroque style.

Played (option 1):

Measures five and six recognize the new leading-tone lower neighbor in the analysis over the barline, featuring the Bb for these measures. Measure seven ends the previous sub-phrase on the C, which acts as the tone of resolution for the Ds marked with asterisks in measures five and six. Measures eight and nine are same in both this and the next version, following the rhythmic principle of tones of short duration off the beat resolving to longer tones on the beat.

Played (option 2):

The first two measures are the same as in the first option. Measure three treats weak beats two and three as pick-ups – a 2-3-1 grouping and a more Classical style than the first solution. Measures five and six start the second phrase by calling attention to the new chromatic leading tone to the dominant by making it the first tone of the pick-up sub-phrase over the barline. Measure seven ends the previous sub-phrase on the downbeat Eb as a resolution of the F from the beginning of the previous bar but leaves the following C as an independent tone, which does not work out well for the total line.

The first solution works well in a Baroque style in measures three and seven, and I prefer this version. That said, what matters most to creating an expressive performance is establishing common sub-phrase groupings.

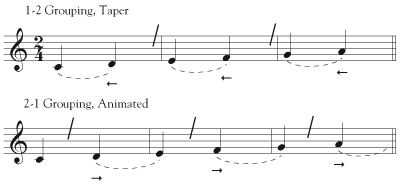

Beat Groupings in Common Meters

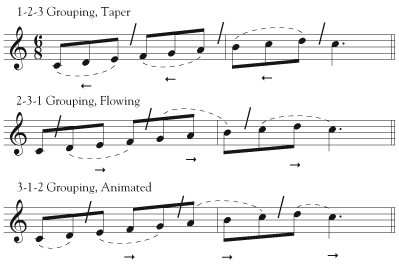

When addressing sub-phrases that have a scale-line configuration or moderately shaped contour, use a numbering system according to the note groupings. Select the grouping that best fits the style of the piece from within the meter, flowing or animated. When within the meter, taper the grouping.

Meter in 2:

The first three measures show tapering within the meter. The last three measures group notes over the barline, producing a more animated feel. In both cases, they are light expressions.

Meter in 3:

Possibilities for three-beat measures include sub-phrases within the meter, a flowing 2-3-1 grouping over the meter, or a 3-1-2 animated grouping. In all three versions, the second and third beats are light expressions.

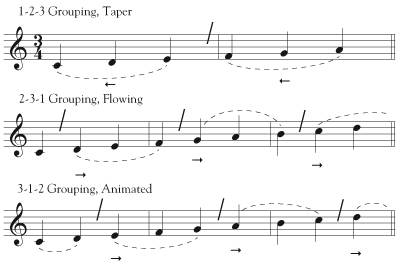

Meter in 4:

Meters in four offer numerous options. The first line shows a tapered flowing within the meter, a 1-2-3-4 grouping. The second shows an over-the-meter long flowing 2-3-4-1 grouping. The third line shows an intermediate flowing over the meter (3-4-1-2) usually used by contour. The fourth line is an animated 4-1-2-3 grouping over the barline.

Meter in 2 with a Pulse Subdivided in 3:

The possible groupings here are similar to those of three-beat measures.

Some composers indicate expressive sub-phrase groupings as best they can within the limitations of music notation, but others do not, leaving it up to the conductor to make such decisions. In my opinion, expressive phrasing is the least taught subject in most of our colleges and universities, so it is not unusual that most instrumental teachers struggle with this in both their conducting and playing. In recent years, I have included an expressive phrasing suggestions page in all my scores published by Northeastern Music.

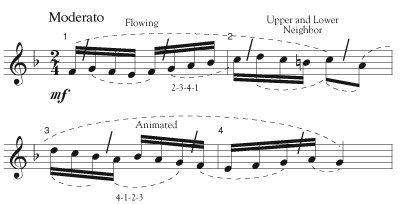

Meter in 2: Scale-line groupings in context of a melody. As written:

Played (option 1):

This first option uses a 4-1-2-3 animated grouping in the first long phrase. The cadence in measure two stays within the meter. The second long phrase features the two half steps in the scale (Bb-A-Bb and F-E-F), resulting in a 3-4-1-2 grouping.

Played (option 2):

This option uses a more flowing 2-3-4-1 grouping in the first long phrase. The half-cadence in measure two takes the resolution of the upper and lower neighboring sixteenth tones to beat two, resulting in the following 8th note as a pick-up to the next sub-phrase. The second long phrase is more animated, applying a 4-1-2-3 grouping.

Both solutions are musically valid. It is a choice of style and which version fits the overall flow of the section of the piece as a whole, animated or flowing.

Meter in 3 – Scale-line groupings in context of a melody:

.jpg)

This example uses both the 3-4-1-2 and 1-2-3-4 groupings. The melodic configuration in measure one clearly indicates the 3-4-1-2 grouping. In measure three, the disjunct nature of the sixteenth-note figures clearly indicate a 1-2-3-4 grouping. The implied diminuendo indicated below the staff applies the phrasing principle that rising lines that do not resolve are usually diminuendos.

Meter in 4 – Mixed scale-line groupings in eighth-notes:

.jpg)

The first antecedent phase uses a flowing 2-3-4-1 grouping as indicated by the melodic configuration changing direction. A neighboring tone configuration is also possible in the beginning, but it would be more animated, creating a 4-1-2-3 grouping. I prefer a more flowing grouping, which is why I chose a 2-3-4-1 grouping. The consequent phrase uses the neighboring tone configuration resulting in a more animated 4-1-2-3 grouping and stylistically contrasts the flowing first long phrase.

Phrasing Within and Over Slurs.

.jpg)

Frequently composers will slur sixteenth or eighth notes in groups of four. Depending on the tempo, it is possible to create sub-phrases that flow from within one group of slurs into another according to the contour of the line. In most cases, legato slur markings should not be taken as phrase markings unless they match the contour or configuration of line. In this case, they are pure articulations and sub-phrases should be applied for expression and interest for both the player and the listener.

Ensemble Phrasing Analysis with a Condensed Score

Notice that every element in the score on the previous page progresses over the meter or pulse. My choice for the accompaniment uses the longer sub-phrase eighth-note grouping of 2-3-4-1. If no grouping is applied, the mind tends to revert to note-to-note thinking, making the tempo unstable; the repeated eighth notes become uneven over time and boring to play. The grouping helps keep the players focused on the task at hand and avoids boredom with the repetition. The bass line is over the barline in a 2-1 grouping and the melody uses an animated &-1-&-2 eighth-note grouping in most of the measures. When playing an anacrusis, be sure to think of the salient note (tone of resolution) so the anacrusis will have the proper inflection. In measure 13 the light high note principle is applied to the Db on the upbeat of two as a pick-up to the downbeat of measure 14.

Holst wrote accents over the first three eighth notes in the melody, calling for a strong statement of the motive. This includes the upbeat of beat one, which would have been light if unaccented.

“Intermezzo” from First Suite in Eb by Gustav Holst – rehearsal letter B:

.jpg)

Summary

There are limitations in indicating expressive phrasing in our system of music notation, but there are concepts that can be beneficial to our teaching and performing. Being aware of the natural inflection within the weak and strong beats in the meter is helpful in determining expressive sub-phrases. Look for activity that creates the wave effect. Young players are just building a memory bank of musical experiences and should be aware of these principles and concepts and apply them to their playing.