Stopped horn, when the hand completely covers the bell, is an extremely effective but sometimes misunderstood technique. Passages for stopped horn occur in nearly every genre of music from solos to large concert band works. Mutes and mute technique can also be problematic for intermediate players. Even deciding the correct mute to use for a given passage can be tricky because often there are several workable options.

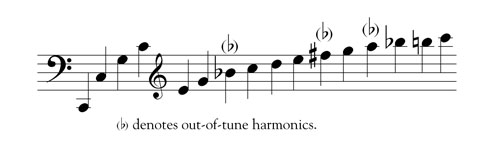

One reason stopped horn technique is misunderstood is that professional horn players and acousticians do not agree entirely on what happens when the horn is stopped, but there are two main theories One belief is that closing off the bell lowers the resulting pitch to 1⁄2 step above the next lowest harmonic. This theory can be tested by examining the harmonic series.

According to this theory, stopping the written C5 on the open F horn should produce a slightly flat B, a half step above the slightly flat harmonic directly below it. This theory is true as long as the player allows the hand stopping motion to lower the pitch of the open note gradually.

Another theory is that fully stopping the horn raises the resulting pitch by 1⁄2 step, requiring that players finger pitches 1⁄2 step lower than written on the F horn. According to this view stopping the written third space C on the open F horn should produce a C sharp 1⁄2 step above. This view holds when the player attempts to maintain the pitch being played, which produces a tone popping up to the next harmonic.

Both theories are correct. The first one makes sense acoustically as gradually closing the hand in the bell does lower the pitch. The second view makes sense in terms of fingering because we must finger pitches 1⁄2 step below the written note on the F horn to obtain the correct pitch. A close study of the horn’s harmonic series shows that both explanations are really the same. The B flat side of the horn complicates the issue more because while the B flat side still follows the first theory, attempting to keep the same pitch as suggested by the second theory, raises the written pitch by a 3⁄4 step, rather than a 1⁄2 step.

A Practical Approach

While the competing theories are intellectually interesting, directors are more concerned with helping their students produce an acceptable stopped horn sound. Proper open horn hand position is essential. Hand positions vary among professionals but there are some characteristics of good right hand position:

• Fingers bent at the knuckle and fairly straight from the knuckle to the tips of the fingers.

• Thumb close against the side or top of the index finger with no spaces between.

• No spaces between fingers.

• Palm slightly cupped as if swimming freestyle or holding shampoo.

• Right hand conforming to the shape and size of the bell, producing a slightly rounded shape when the back of the hand is pressed against the far right side of the bell.

• Knuckle of the thumb lined up with the bell brace and inserted until the thumb touches the upper part of the bell and the bottom edge of the hand makes contact with the bell.

The move from open to stopped horn should be as efficient as possible and should not require a drastic shift in hand position. Here are some additional tips that should help in practicing stopped horn hand position:

A proper stopped horn sound is compressed, brassy, and even a bit nasal. This sound takes a leak-free seal between the right hand and the horn’s bell throat. The poor intonation and uncharacteristic sound that are sometimes produced with stopped horn can be fixed by adjusting the hand positions. Some players will be tempted to push the hand further into the bell, but this can cause pitches to be very sharp. This problem is more difficult for players with relatively small hands. Keep the thumb pulled back and out of the way of the hand.

Instead of trying to place the hand directly across the front of the bell, try closing the bell off at an angle, which can produce a better seal. The British performer Pip Eastop has developed an ingenious device to help those with smaller hands. His invention is easy to make, inexpensive, and really does work. The key is getting students to take the 30 minutes necessary to make it. (A full description and details on construction are available at www.pyp.f2s.com/framesets/inventionsframeset.htm

Players should strive for as much contact as possible between the heel of the hand and the bell throat. Having students imagine they are squeezing the horn between their left and right hands is sometimes helpful in getting a proper seal. For those with bony hands slightly twisting the heel of the palm so that even more flesh is in contact with the bell can help.

Another common problem faced by players is the dramatic increase in resistance cause by fully covering the bell. Frequently students are not blowing assertively enough against the resistance to get the desired buzz when composers ask for stopped horn. Filling out the sound of stopped horn will also help with intonation and articulation problems.

Stopped Horn Fingerings

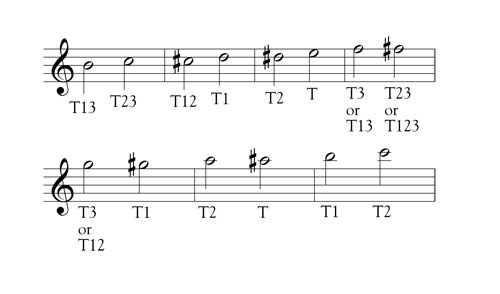

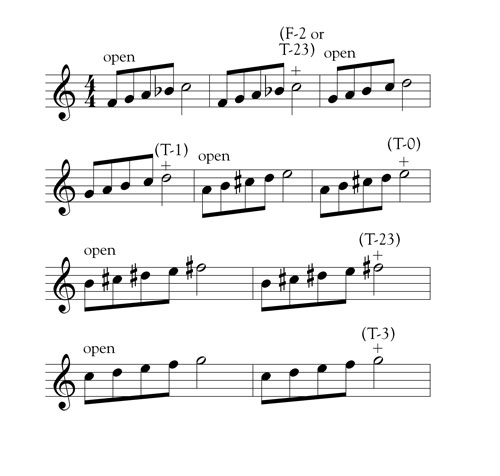

Players should generally be fine to use F horn fingerings and transpose done a half step between written E4 and C#5, the part of the range that presents the fewest intonation and articulation problems. For the higher register, F horn fingerings will work, but problems of accuracy and intonation will become more exaggerated. For this range try the following fingerings. (The T indicates that B flat horn fingerings should be used.)

Although these fingerings will work on many horns, encourage students to try alternate fingerings. The fingering used is less important than producing a good sound that is in tune.

The notes below written C4 often present the greatest difficulties on stopped horn with articulation and intonation being the most common. Although I recommend that students learn to play in this range without the aid of a transposing stop mute, more and more professional players are using these. The mutes produce a louder, more stable stopped sound, and are relatively inexpensive. They usually require that players transpose the written pitches down a half step to obtain the proper F horn fingerings. Be aware that a hand-stopped sound is different from that of a stop mute. Although stop mutes and hand muting can be compatible within a section, avoid mixing stopped horn and straight mute timbres unless the composer requests this combination.

When rehearsing stopped horn passages it is good to let players perform the part on open horn a few times so they can get a better sense of pitch and articulation before attempting to play the part stopped. Once they do play the part stopped, encourage them to blow forcefully to experience the sensation of producing a compressed, brassy sound.

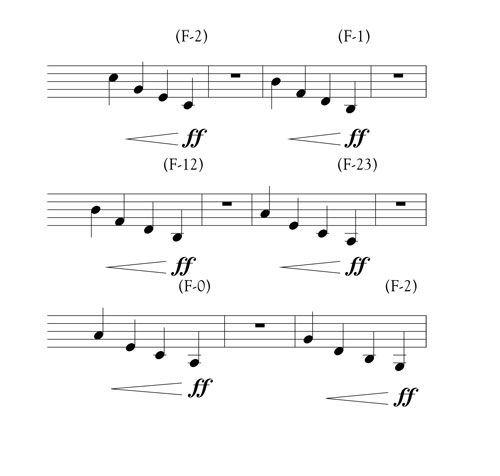

Stopped Horn Drills

These exercises will help beginning to intermediate players learn stopped horn technique. If practiced daily these can establish a foundation for more advanced stopped horn effects. Simplicity is the goal in these brief passages, and they progress from easy to difficult. Students should play the exercises with a tuner and metronome whenever possible. Here are some hints to remember:

• Check intonation frequently with a tuner or drone. Compare intonation from stopped to open positions.

• Insist on a brassy, compact, and nasal stopped sound. Producing this sound quality, especially in the lower register, will require huge amounts of air.

• Check hand position frequently for air leaks.

• Rely solely on the ear for accurate intonation until muscle memory is developed.

• Take frequent breaks until en-durance is developed.

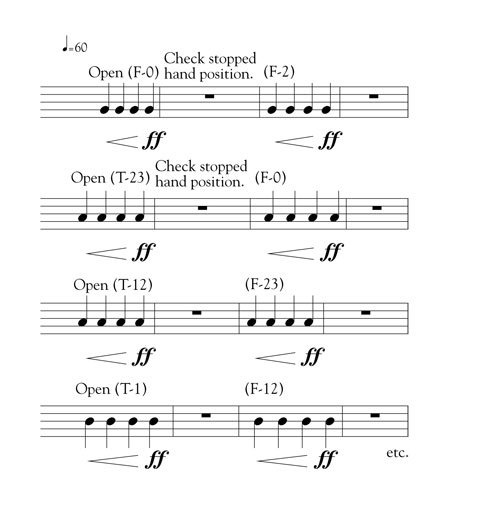

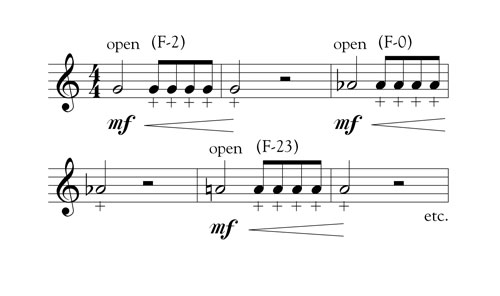

Exercise 1. Hand position and middle register articulation and intonation.

Exercise 2. More rapid articulations.

Exercise 3. Stopped/open horn coordination and upper register practice.

Exercise 4. Low register practice.

Terms and Symbols

for Stopped Horn

+

stopped

gestopf

bouche

chiuso

Mutes

Mutes present less of a problem than hand stopping. The most important things for younger players to do are acquire a good mute and learn a few basic concepts of muted horn technique. Players have to learn not to seat the mute too tightly in the bell of the horn. The mute should only be snug; shoving the mute too far into the bell can cause all sorts of articulation and intonation difficulties. All of the stopped horn exercises can be used to practice muted horn. Makers of horn mutes include Denis Wick, Trumcor, Lewis, Engemman, Ion Balu, and Humes and Berg.

For quick mute changes a wrist strap is extremely helpful. If students are using a mute that does not come with a wrist strap, one can easily be made using an eye hook and some sturdy string.

When students start to get the hang of playing stopped and muted, have them practice well-known tunes on open horn first, then stopped or muted. As long as students understand the correct technique without forgetting correct phrasing and musical nuances, stopped or muted horn can be beautiful.