These interpretive notes are general observations gleaned from a lifetime of study and performance of Gustav Holst’s Second Suite in F. The notes pertain to Colin Matthews’s revised edition of the Second Suite that was published by Boosey & Hawkes in 1984 (on the 50th anniversary of the composer’s death). Matthews’s version is based on the autograph manuscript and so the preferred performance edition.

An interpretation of the Second Suite in F should start with the source material that inspired and motivated its creator. Holst comments in the introduction to the 1922 condensed score (and not in any other published score) that “The Suite is founded on old English Country tunes.” Specifically, two folk dances and five folk songs:

1. March – Morris Dance (“Glorishears” and “Blue-eyed Stranger”), “Swansea Town,” and “Claudy Banks”

2. Song without words “I’ll love my Love”

3. “Song of the Blacksmith”

4. Fantasia on the “Dargason” (Country Dance) introducing “Greensleeves”

The folk dances in the Suite were collected by Cecil Sharp; four of the five folk songs in the work were collected by George B. Gardiner. Directors should study what has been written about the folk music and listen to available recordings. Additional clues to interpretation may also be gleaned from the poetic texts of the folk songs.1

The folk tunes in the Second Suite in F are predominantly in song or strophic form. In strophic form a folk song is repeated with each stanza of text. Holst was not only a master at combining diverse folk songs and dances in one movement, but he was also highly skilled in varying the rhythms, harmony, dynamics, orchestration, texture, and style elements when a folk tune was repeated.

Instrumentation

Holst was clearly thinking of a British military band when he initially composed the Second Suite in 1911, and also when he revised the work eleven years later in preparation for its spectacular first performance by the Royal Military School of Music Band at Royal Albert Hall, London, June 30, 1922. Changes in military band instrumentation from 1911 to 1922 basically involved replacing B-flat baritone horn with B-flat tenor saxophone and adding parts for horns 3 and 4. Note, however, that in neither version of the work did Holst use the following instruments: trumpets; alto, bass, or contrabass clarinet; soprano, baritone, or bass saxophone; contrabassoon or string bass. Parts for most of these instruments are included in the 1948 Boosey & Hawkes edition of the work and in Colin Matthews’s 1984 revised and edited version. Colin Matthews’s edition is preferred for performance today as the instrumentation is clearly explained in the introduction to the score – directors can perform the work with the original small band instrumentation or with full band instrumentation.

In both the published and autograph scores of the Second Suite in F, Flute & Piccolo are listed as one part. It would appear that except for a few passages marked flute or piccolo, the piccolo doubles the flute an octave higher throughout. That dubious situation should be resolved by the conductor. Edit the Flute & Piccolo part carefully and transfer your marks to the score and parts.

Note that the Solo & 1st Clarinet part in Matthews’s edition is the same as Holst’s autograph score. That is, except for the first 17 measures of movement two, the part does not divide. In the autograph score Holst wrote “Melody for oboe or clar” at the beginning of movement two at the top of the page as if an afterthought. If the solo clarinet part is rewritten for oboe (recommended), then the notes in original oboe part (first 12 measures plus three beats) must be rescored for Solo B-flat Clarinet because most of the oboe notes are not covered elsewhere.

Although Holst only wrote parts for 1st and 2nd B-flat Cornet in the autograph score, the 1st B-flat Cornet part divides in the following passages: Mvt II – last two measures; Mvt III – letter C to the end of the movement; and Mvt IV – measure 201 to the end. As a result, at least two players should cover the part with a minimum of three players in the section. Check every part before rehearsals begin to uncover other discrepancies.

Note that only cornets, not trumpets, are called for in the autograph score and in Matthews’s revised edition. If the preferred cornet sound is not available, then distribute the parts among your trumpet players and ask them to try to darken their sounds by using a deeper cupped mouthpiece, a larger bored trumpet (if available), and playing slightly into the music stand.

Holst originally scored the Second Suite for two horns in keeping with the English military band instrumentation of 1911. When he revised the score in 1922 he added horns 3 and 4. Most of the time throughout the first three movements of the revised score, Holst doubled the 1st and 2nd horn parts with 3rd and 4th horns. In the last movement of the autograph score, however, Holst wrote separate parts for horns 3 and 4 at the bottom of the page to reinforce the second appearance of “Greensleeves” (climax phrase) beginning one measure after letter G. This reinforcement is good if the work is played by a large band, but not absolutely necessary if performed by a small band with one player per part and no ad lib instruments.

Holst’s 1922 revised version of the Suite is a masterpiece of economy and lucidity with regard to orchestration. Although I prefer to perform the work with the original instrumentation (minimal of doubling of parts, around 24 players), I can recommend medium, large, and even extra large wind band performances as long as the instrument parts are balanced and the ad lib parts are judiciously edited. This is particularly important with regard to bass and sub-bass single and double reed instruments.

Notes for Each Movement

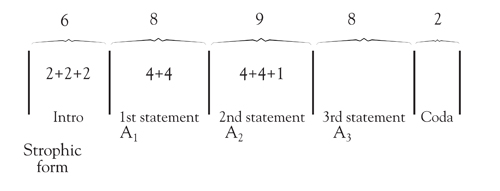

I. March – The first movement is in ternary form – ABA. Although three folk tunes are ingeniously employed in this movement, the music is nonetheless a straightforward march, so the rhythm, spirit, and style of the march should be maintained, whether in simple or compound time. Sing the folk song “Claudy Banks” (letter H) to determine a tempo that will work for the entire movement.

After a short, two-measure introduction in which a melodic fragment of the first tune is stated in the low brass and answered antiphonally by the upper woodwinds, Holst introduces “Morris Dance.” This is a combination of two handkerchief dances – “Glorishears” and “Blue-eyed Stranger.”

The “Glorishears” dance tune is 16 measures long – eight measures of brass followed by eight measures tutti. An eight-measure bridge for woodwinds, horns, and triangle (the second half of “Blue-Eyed Stranger”) links a verbatim restatement of “Glorishears” beginning at letter C. Following the restatement, a four-measure transition leads to the next tune which begins at letter E. “Swansea Town” is 32 measures long and includes a 16-measure statement by the euphonium with low brass accompaniment followed by a 16-measure restatement by the full band, beginning at letter G.

At letter H, after a one-measure introduction (with meter and key change), the third folk tune, “Claudy Banks,” is introduced. This melody, which is 24 measures long (three groups of eight), is also stated twice, first by single reeds and later, at letter J, by full ensemble. The da capo repetition of section A – “Morris Dance” and “Swansea Town” – rounds out the movement. Notice the unusual, yet stunning, modulation over the bar line at letter H from the key of F major to B-flat minor (section B – “Claudy Banks”). Normally the middle section or trio of a march modulates to the major subdominant key. Compare the chord relationship in movement two to the previous key scheme. In movement two the tonic chord is D Dorian minor and the subdominant chord B-flat major – the opposite of the key scheme of the March.

When performing the first movement of the Second Suite, be sure to bring out the descending line in the low reeds and brass in measures 16 and 40 (“Morris Dance”). Holst beautifully captures the sound, spirit, and style of Morris dancing in the scoring of “Glorishears” and “Blue-eyed Stranger” (starting at letter A). The sounds of the pipe and tabor (favored instruments traditionally used to accompanying Morris dancers) are emulated through the use of snare drum and high woodwinds, especially flute and piccolo. The triangle in “Blue-eyed Stranger” (letter B) brilliantly replicates the sound of jingles typically strapped around the legs of Morris men. At measure 42, the transition from “Morris Dance” to “Swansea Town,” let the cymbals ring (laisser vibrer) and decay naturally to blend with the upper woodwinds.

Notice in the first statement of “Swansea Town” (letter E) the singular use of tenuto marks over the three half notes in measures 65-66. Holst apparently wants expressive emphasis on these notes, possibly to reflect the text of the first verse of the folk song which reads at this point: “you, fine girl.” Curiously, Holst does not mark these notes tenuto when the folk song is restated. The four-measure snare drum roll marked crescendo (77 to 81) should be gradual and smooth, and should lead to a climax in measure 81 (not 79); the snare drum roll peaks two measures after the band climaxes. As indicated previously, let the cymbals and bass drum half notes (82-86) vibrate and decay naturally. The percussion accompaniment to “Swansea Town” is a bit of tone painting that reflects the third verse of the chantey and tells of a violent storm rising at sea that tosses an old ship about and tears the rigging. The snare drum, bass drum, and cymbals depict wind, waves, thunder, and lightning. In his choral folksong settings of “Swansea Town” Holst created very different tone painting effects with the third verse of this sea song through the use of rising and falling chromatic lines in octaves, crescendos and decrescendos, and tempo piu mosso that all depict stormy ocean waves.2

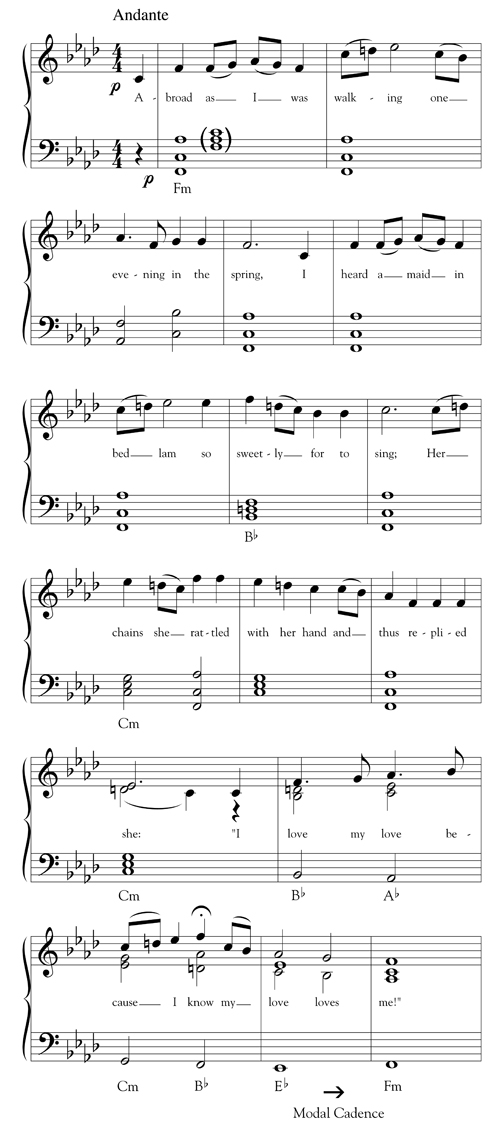

II. Song Without Words “I’ll Love My Love” – Holst originally scored this very expressive music for 20 instruments: flute, oboe, E-flat clarinet, 3 B-flat clarinets, alto and tenor saxophone, 2 bassoons, 3 B-flat cornets (the 1st part divides at the end), 2 horns, 3 trombones, euphonium, and tuba. When played as originally scored with one player per part (recommended), this is sublime chamber wind music. Whether performed with solo instruments or, as customary, with multiple doublings, the music is profoundly beautiful and moving.

Expressive dynamic nuances and tempo rubato may be freely applied to this romantically conceived ballad. In the choral folksong arrangements of “I love my love” Holst employed expressive markings that do not appear in the band score including affettuoso, con passione, and sotto voce. This is understandable given that he arranged six verses of the folk song for voices, whereas in the band score he states the folk song twice (the solo part in both statements is marked con espress.). It is useful to keep the stylistic markings of the choral arrangements in mind when conducting this movement.

The overall form is fairly simple. After a short, two-measure introduction establishing the F Dorian mode, Holst introduces a “Song Without Words ‘I’ll love my love.’” This 16-measure folk song is restated with a rolling eighth-note accompaniment beginning at letter A. The movement ends with a three-measure coda, an extension of the flowing eighth-note accompaniment.

With a few simple major and minor triads, Holst composed a beautiful harmonic setting for this lovely folk song. The bright sounding B-flat major chord (subdominant) corresponds with the word “sweetly” in the folk song; this is tone painting at its best. Other places to notice are the very expressive use of an appoggiatura in measure 11-12 (with the poignant words “thus replied she”) and the wonderful modal cadence at the end. Play the accompaniment at the keyboard while you sing the words to this heartrending folk song to gain a fuller appreciation of the music.

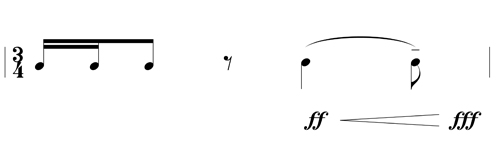

Both appoggiaturas in this movement (measures 13-14 and 29-30) should be played as illustrated below; approach each appoggiatura in crescendo giving added expressive intensity and weight to the first note of the 9-8 suspension and reduced intensity to the resolution note.

The ending of movement two (last seven measures) can be treacherous and should be approached with care. As you move (ad lib.) toward the fermata in measure 32, gradually soften and slow down the ascending melodic line. After holding the fermata momentarily, gently and smoothly release the hold with no caesura. The conductor’s release (give beat three again) should be the preparation for the players to continue. The anacrusis eighth notes played by solo cornet following the fermata should not be hurried and stretch these notes ever so slightly. To avoid an abrupt ending to this movement, the final chord should be held slightly longer than written. Although the addition of a poco fermata at the end is an arbitrary decision, I agree with Frederick Fennell who says that without the fermata “the conclusion comes too suddenly, too abruptly—especially when the trombones [and cornets] withdraw before the basses have secured their not-so-easy low F.”3

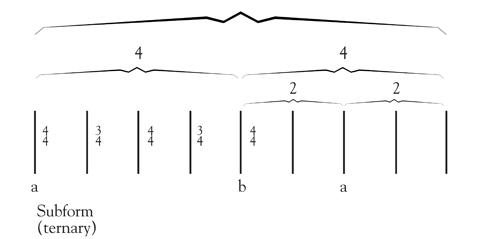

III. Song of the Blacksmith – After a six-measure introduction, actually a two-bar harmonic accompaniment phrase (mixed meters 4/4 and 3/4) played three times, the composer introduces “Song of the Blacksmith.” This energetic folk song is eight measures long and has a ternary subform.

Holst twice restates and varies the tune, first at letter B and second at letter C. To conclude the movement he adds a two-measure extension at the end of the third statement. This coda utilizes a varied rhythmic fragment from the introduction. The internal form of the movement may be diagrammed as shown here.

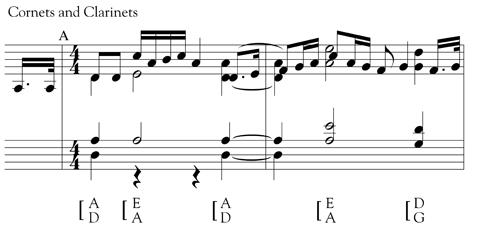

The two-measure chord progression heard at the outset of this movement is harmonically interesting and structurally important.

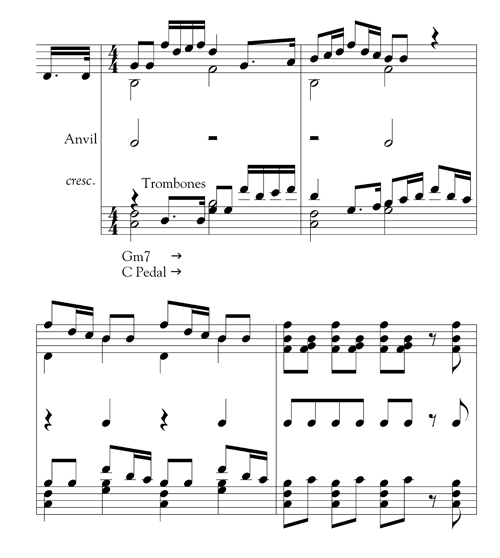

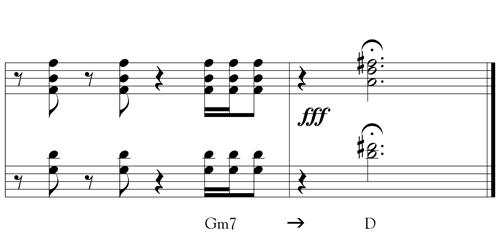

Harmonically, the progression centers on the G minor chord in which all seven occurrences of the chord include the minor 7th tone. Contrasting open-fifth sonorities (C-G and A-E) are used intermittently in this important two-measure progression. The neutral, quasi-jazz sounding Gm7 chord is the ideal sonority for capturing the ringing sound of the blacksmith’s hammer and anvil when played by the brass and percussion. Note in the previous example that the intervals of the outer voices mirror each other. Structurally, the chord progression is used as an introduction and as an accompaniment throughout the movement. The interesting aspect of its use as an accompaniment is that it fits well with the “Blacksmith” tune, no matter which key or tonal center the folk song appears. Holst uses the two-bar chord progression to accompany the first and second statements of the “Blacksmith” tune. However, he alters the first chord of the progression (F major replaces Gm7) when used with the third statement climax phrase.

This brief but important substitution enhances the brilliance of the climax statement, thus revealing the creative genius of a master composer.

Holst employs several other noteworthy harmonic devices in this movement, including:

1. Drone fifths: The use of consonant open fifths to accompany the middle sections of the tune provides needed contrast and resonance.

2. Dissonant pedal point: Beginning at 19, Holst employs a dissonant pedal tone C in conjunction with Gm7 chords to enhance the crescendo leading to the climax statement.

3. Picardy third: The cadence chord progression of this movement is unusual in that the sub-dominant chord is Gm7 and the tonic chord is D major. The appearance of F# in the final chord not only sounds like a Picardy third, it is a Picardy third (recall that the tonal center of the “Blacksmith” tune is, for the most part, D minor).

When the repeated two-bar phrase introduced at the beginning of movement three is used in conjunction with the lively folk song (for example, at letter C), the overall musical effect is rhythmically complex. Noteworthy in this movement are the canonic entrances of the middle section of the second statement of the “Blacksmith” tune (19-20). This rhythmic (and melodic) canon helps to increase the tension leading to the climax statement of the folk song.

The tempo marking Moderato e Maestoso, while allowing for some degree of flexibility, does not mean fast or rushed. Remember that the anvil player has to perform some tricky rhythms. To determine a comfortable tempo, sing the melody with the words, beginning at measure six, and write the metronome marking in the score.

Song of the Blacksmith

The words to "Song of the Blacksmith" provide clues to the interpretation of the music:

For the blacksmith courted me, nine months and better,

And first he won my heart, till he wrote to me a letter.

With his hammer in his hand, for he strikes so mighty and clever,

He makes the sparks to fly all round his middle.

The tempo, once established, should remain steady to the end, except for the lead-in measure before the climax statement of the “Blacksmith” tune which begins at letter C. Here the syncopated pick-up notes should be broadened out and played in crescendo.

Holst captures the sound of the blacksmith’s hammer and anvil by using ringing staccato chords (introduction, accompaniment, and coda) played by brass and percussion instruments. In the choral versions of “The Song of the Blacksmith,” Holst applies a bit of onomatopoeia to his resonant Gm7 chords:

Movement III, Introduction

Movement III, Coda

Practice conducting these places while speaking the word sounds in rhythm.4 Conduct the first example with a vigorous staccato-marcato or gesture of syncopation beat style. Use a neutral preparatory gesture (beat four) to begin the movement, then immediately switch to a syncopation gesture on beat one of the first measure. A neutral preparatory beat should help prevent the natural tendency of players to enter prematurely. In measure 5 begin to indicate a two-measure diminuendo in your conducting, then immediately prepare the melody players for their strong entrance on beat three in measure 6.

The last two measures of this movement are rhythmically treacherous and should be approached with great care. It may be helpful to use a melded or neutral gesture on the quarter rests to counteract the natural tendency to play on these beats. The brilliant D major chord at the end of the movement is scored in favor of the F# (Picardy third). Intonation may suffer here if the second trombone does not play the F# in a raised third position (the normal position for this note). Firmly hold the final fermata chord for at least three beats, then give a convincing staccato-marcato cutoff with both hands.

There are two passages in this movement that seem to dictate a smoother, more legato beat style – the drone accompaniments in measures 11-12 and 28-29, and the tenuto quarter notes in measures 16 and 18 (brass players tend to play these notes too short).

The sound and timbre of the anvil are extremely important in this music. If a real anvil is not available, search for a suitable substitute. Try using a ball peen hammer and a steel plate or large iron pipe to capture the sound of the anvil. For many years, I used a heavy steel plate that once supported a railroad track. It had legs (ribs) that resonated when placed on a percussion trap table.

Holst simply wrote cymbal in the score without clarifying whether the instrument was crash cymbals (cym a2) or suspended cymbal. Look at the cymbal parts, and clarify in the score which instrument is to be used and when. For example a suspended cymbal played with snare drum sticks is appropriate in measures 21-23 of movement three. This marking was used with great effect by Gordon Jacob in his orchestral arrangement of the Second Suite in F (titled A Hampshire Suite, Boosey & Hawkes, 1945).

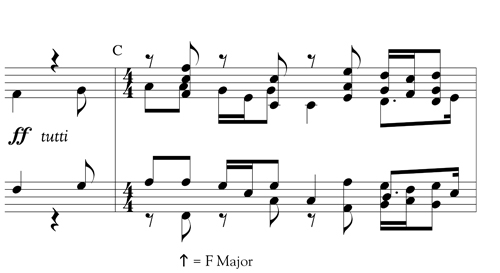

IV. Fantasia on the ‘Dargason’ – The internal structure of this movement does not follow established conventions of form and design; Holst’s title fantasia indicates “a free flight of fancy.” There are 25 complete statements of the eight-measure “Dargason” tune. The rhythms and pitches basically remain the same throughout (although there are octave transpositions); however, the orchestration, dynamics, articulations, and harmonic accompaniments vary greatly. The last 11 measures of the movement (26th statement) is a coda in which the composer employs rhythmically transformed fragments of “Dargason” played antiphonally by solo tuba and piccolo.

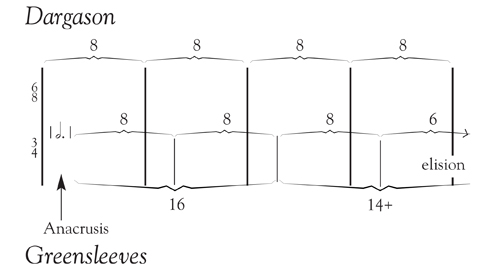

First at letter C (8th statement) and again at letter G (19th statement), Holst introduces “Greensleeves” in brilliant counterpoint to Dargason. In both passages, “Greensleeves” begins two measures after “Dargason” commences (the first note of “Greensleeves” is an elongated anacrusis); this produces overlapping phrases. Both appearances of “Greensleeves” with “Dargason” may be diagrammed as follows:

Both times that “Greensleeves” appears in the fourth movement, the music modulates to Dm, and within each of these sections there is a brief submodulation to F. The chords used to harmonize the first appearance of “Greensleeves” are Dm, Gm, F, and C7. These chords are slightly altered when “Greensleeves” reappears at letter G. Compare the harmonic accompaniment of C-D to that of letter G-H in the score. In both sections, a deceptive cadence (C7 to Dm) is used to transition into “Greensleeves.”

Note in the first and each succeeding statement of the eight measure “Dargason” melody that there is a staccato articulation over the last eighth note in first, third, fifth, and seventh measures, and over the first eighth note in the sixth measure. Fennell suggests that the players be instructed to whistle the “Dargason” tune to hear the light character of the melody. Read Colin Matthews’s introductory score notes with regard to the tenor saxophone doubling of the alto saxophone solo at the beginning of movement four. I omit the tenor saxophone doubling if the piece is performed by a small wind band with a skilled alto saxophone player.

The crescendo beginning at 25 and continuing to 40 should read cresc. poco a poco and should lead to letter B, the first fully orchestrated statement of “Dargason.” The “Greensleeves” melody at letter C should be played mp and cantabile as marked (this tune is in contrast to “Dargason”). The ensemble problem here is that, when played cantabile, “Greensleeves” has a tendency to drag or get behind due to the hemiola construction of the rhythms and meters – 6/8 combined with 3/4. To avoid this potential problem instruct those who play “Greensleeves” to be sure that they play on the ictus of the conductor’s downbeat, and conduct one beat to the bar in these passages.

To enhance the subito contrast of dynamics at letter F, add a crescendo in the preceding bar, then immediately reduce the number of players to one per part at letter F and continue one player per part for eight measures. To bring out the ascending chromatic bass line, encourage the performers to play these lines in crescendo. (In the Finale of St. Paul’s Suite Holst added pesante to this ascending bass line). Consider the 24 measures from letters F to G as an orchestrated crescendo that leads to the peak climax phrase beginning at letter G. Beginning at letter H, all solo lines should stand out slightly against the background of the accompaniments; dynamics may have to be adjusted to achieve correct balances. The same may be said about the antiphonal interplay of solo tuba (marked pp and staccato) and solo piccolo (marked ppp and legato) in the last 11 measures of the movement. Tone quality must not suffer for the sake of dynamics.

The final resounding F major chord, should surprise the audience, and should not be too short. To stress the importance of this sonority, rehearse with a fermata; repeat and gradually shorten the duration until it is the correct length, in tune, and resonant.

In performing this movement, the marking Allegro Moderato allows for some flexibility in choosing a tempo. A good tempo may be gleaned from the melody “Greensleeves,” conducted moderato, one beat per bar. Moderato is an important modifier judging from the following interpretive remarks attributed to Imogen and Gustav Holst by biographer Michael Short:

The Finale [of St. Paul’s Suite for String Orchestra] is a transcription of the fourth movement of the Suite No. 2 for military band, with the insertion of five further variations, and the combination of ‘Greensleeves’ and the ‘Dargason’ has the same exhilarating effect as in the wind band version; school performances sometimes being enlivened by the pupils singing the traditional words of ‘Greensleeves,’ with tambourines brought in at the climax and ‘Ha!’ shouted loudly on the last chord. The use of words meant that the movement could not be performed at too fast a tempo, and Imogen Holst considered that the correct speed is the one which is most suitable for dancing. Holst himself liked the two heavy accents of the 6/8 bars to continue against the 3/4 on the appearance of ‘Greensleeves’, to emphasize the rhythmic contrast between the two tunes (‘Kinsey and the LSO second violins once gave it to me in grand style,’ he recalled, ‘The effect was intoxicating’).5

There are important clues to interpretation in this quotation, not the least of which is Holst’s liking of the “intoxicating” hemiola accent effect of 2 against 3 when "Greensleeves" is combined with "Dargason." Short’s comment6 about “school performances sometimes being enlivened by the pupils singing” is a wonderful idea and highly recommended for band concerts. Some modification and adaption may have to be made to the verses to make them fit the melody in the band score. The singers, whether they are members of the band or from a choir, should have a voice range of just over an octave – from d above middle c to top line f in the treble staff. That fits the general range of sopranos and tenors (an octave lower). The shouting of “Ha!” and the addition of more tambourines on the climax chord will surely produce an exhilarating and resonant finale to a wonderful composition that remains a masterwork of the band repertoire.

Errata

The errata below pertain to Colin Matthews’s revised edition, which is based on the autograph score (Boosey & Hawkes, 1984). Only errata deemed important for performance are listed.

Overall:

• Instrumentation – In the instrumentation on the first page of the score mark the following instruments ad lib or optional: B-flat Bass Clarinet, E-flat Baritone Sax., and B-flat Bass Sax. as these instruments were added to accommodate performances by modern bands.

• E-flat Clarinet – The part for this instrument (not the score) reads “E-flat clarinets”; this should be singular as the part doesn’t divide.

• Solo & 1st B-flat Clarinet – In the score there is one music staff in mvts. 1, 3, and 4 (the part is the same); however, mvt. 2 has two staffs – one for Solo B-flat Clarinet and one for 1st B-flat clarinet (the part divides). To make matters more confusing, separate parts are printed for Solo Clarinet and 1st Clarinet, with E-flat Clarinet cued notes printed right on top of the solo line in the Solo Clarinet part (first 14 measures of movement 2). Examine all printed parts to the Second Suite for discrepancies and mark the score appropriately.

Movement I:

• Measure 12 – Flute and Piccolo (score only): the half note should be C (2nd line above the staff), not D.

• Measure 46 – Euphonium (score only): mark solo at the beginning of the folk tune.

• There are several articulation inconsistencies in the “Claudy Banks” folk song (parts only) beginning at letter H; make corrections to the parts following the articulations given in the score.

Movement II: None

Movement III:

• Measure 6 – Horns 1 & 2 and 3 & 4 (parts only): add slur over the notes on beat 3.

• Measure 12 – Horns 1 & 2 and 3 & 4 (score only): change last note in the measure to written D (one step below printed E).

• Measures 14 – Solo & 1st Bb Cornet (score and part): mark solo over the pick up notes to the folk tune which begins on beat three of this measure. NB: There are several articulation discrepancies in the Cornet solo passage (measures 15-18) in both the score and part; use the Horn line from the score (measures 7-10) as a guide to correcting the faulty articulations of the Cornet solo.

• Measure 28 – Basses (part only): 4/4 time signature missing.

Movement IV:

• Measure 31 – Clarinet 2, 3 (score only): add slur over first two notes in the measure.

• Measure 208 – Cornets 1 and 2 (score only): write “senza sordino” in the score (parts are correct).

Endnotes:

1 Folk Songs & Dances in the Second Suite in F by Gustav Holst (Whirlwind Music Publications, 2011). Volume 3 of the Anthology Series: Folk Songs & Dances in Wind Band Classics edited by Robert J. Garofalo.

2 Six Choral Folk Songs, Op. 36b. Arranged for Mixed Voices by G. T. Holst. Includes: “Swansea Town,” “I love my love,” and “The Song of the Blacksmith” (J. Curwen & Sons Ltd., 1917). Arranged for Male Voices by G. T. Holst. Includes: “Swansea Town,” “I love my love,” and “The Song of the Blacksmith” (J. Curwen & Sons Ltd., 1925).

3 "Basic Band Repertory" (The Instrumentalist, 1980), p. 42.

4 Adapted from Lead & Inspire: A Guide to Expressive Conducting by Robert Garofalo and Frank Battisti (Whirlwind Music Publications, 2005), p. 115.

5 Michael Short, Gustav Holst: The Man and his Music (Oxford Univ. Press, 1990), p. 106.

6 Michael Short commented to me in an email (4.8.11) that: “It was Imogen Holst who told me about the St Paul’s Suite being performed with singing and tambourines, etc. It seems that there was also dancing as she always said that the last movement should not be played too fast – the correct tempo was the one most suitable for dancing. I doubt whether this went on in any other British school – it was just Holst’s way of involving as many girls as possible in the performances.” Incidentally, Imogen Holst recorded the “Finale” of St Paul’s Suite with this tempo: 6/8 time, dotted quarter = 132 and 3/4 time, dotted half = 66.