Movie Audiences talk about summer blockbusters for months, as directors across the nation plan which pieces they will be playing the next year. As rehearsals begin in fall, the big summer movies are out of theaters, and by concert time DVDs are only months away. Students are usually thrilled to play something exciting and popular, while audiences are equally thrilled to hear a concert band rendition of a new or favorite theme from a film.

Movie Audiences talk about summer blockbusters for months, as directors across the nation plan which pieces they will be playing the next year. As rehearsals begin in fall, the big summer movies are out of theaters, and by concert time DVDs are only months away. Students are usually thrilled to play something exciting and popular, while audiences are equally thrilled to hear a concert band rendition of a new or favorite theme from a film.

Many band directors are familiar with the dilemma of finding good-quality film music that gives students a worthwhile musical experience. The secret is to select film music just like other work for the ensemble. Of the various books available on categorizing band music and transcriptions, Thomas Dvorak’s Best Music for Band series lists truly musical pieces that are well crafted for students. Unfortunately, there is no such book with film music. It is an open field full of hundreds of titles left to band directors to decide which is good and will influence students musically and not be another hot fad lost in the library.

Films take months, even years to make, with composers brought in for the last few weeks to add the final touch of music. Sadly, a producer or even a small committee of producers and directors, who may have little if any musical background, make the decisions for the music. Often composers’ musical judgments are overruled for more popular trends or even for financial reasons. Elmer Bernstein wrote in Tony Thomas’s Film Score: The View from the Podium, “The getting together of a well-trained composer and the average producer or director is often akin to having a heart specialist try to convince an Amazonian tribesman to submit to open-heart surgery.”

Many times composers are still limited to their musical output simply by the financial situation of a film. Some film budgets may not include the expense of musicians for an orchestra. For those with a music allowance, limited finances can dictate the size of the orchestra, the amount of music scored and played, or even the type of music in the film.

Does this mean band directors should pick a score based on the amount of money given for the music or who produced the film? Yes and no. Some films have huge budgets and music that sounds big but lacks character and quality; while some small films or even unpopular films forgotten by most might have that small element of quality that band directors find in good music.

A film score that has a direction has a sense of both unity and development, following the development of the story. Quality in direction takes place when the music develops alongside the story, which results when the director and composer share a similar vision. Henry Mancini once wrote in Tony Thomas’s Film Score: The View from the Podium, “One thing we had in common was an agreement on the common goal of what was needed for the film – what it was about and what the music could be expected to add to the film.”

Many other elements make a good film score: originality, a memorable theme or concept, the ability to support dialogue and a story line, the ability to be convincing, and whether the score can stand independent of the film. While these qualities contribute to good film music, they do not necessarily contribute to a good concert band piece.

From time to time everyone has seen televised broadcasts of the Boston Pops Orchestra playing medleys of different pop genres, Fourth of July patriotic music, popular songs, Disney tunes, or musicals, and even medleys of a specific movie genre. While they are all wonderful settings of music, some band directors rightfully question whether they want students learning about music from them.

The transcription developed at a time in music history when directors wanted to show the musical community that the concert band was legitimate. In a 1965 article in the Music Educators Journal, David Whitwell wrote, “By the 1930s the association of bands and popular transcriptions had become inseparable. In 1938 two influential books appeared: Prescott and Chidester’s Getting Results with School Bands and Richard Goldman’s The Band Music. The two books suggested program materials consisting of over 85 percent transcribed music.” The goal was to have people view concert bands as serious ensembles, not something with only entertainment value.

The transcription still is important among great band pieces. Elsa’s Procession to the Cathedral transcribed by Caillet, Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in D minor by Moehlmann, Festive Overture by Hunsberger, and Mars by G. Smith are among the great transcriptions that are standard repertoire in band programs. I mention these titles only because most every film score that bands play is a transcription of an orchestral score.

Because film scores have the added element of a transcriber, band directors should look for publications that have good musical qualities outside of the film as well as good musical quality in the arrangement. For example, while looking through a music warehouse, I once found five concert band arrangements of Henry Mancini’s The Pink Panther by five different arrangers.

One arrangement followed the form of the original theme from the 1963 movie while the others had simpler forms. The main melody featured an eighth-note swing in most of the arrangements, while the first piece had a dotted-eighth note, 16th-note configuration in the solo. The original theme had a middle section with a solo, and half of the arrangements had solo sections. One piece repeated the theme twice. Each piece had a specific quality to it, but only one was close enough to the original thing to be considered a straight transcription and not just an arrangement.

Another example is the music from Harry Potter, which can be thrilling for young musicians to play, especially if they have read the books. I found four different arrangements, three with the main melody simplified. Two featured the music to “The Prisoner of Azkaban,” of which one had the correct melody, and the other had a simplified version of the sweet B theme. The movie theme featured a recorder that could be substituted with a flute, and all the arrangements had the substitute instrument. In the movie the entrance had fast runs in the percussion and high woodwinds that were simplified in every arrangement. This is something I have always encountered in music for young bands.

Band directors should praise the qualities of arrangements for young bands because playing simplified parts well makes students more confident in their abilities. At the same time I often question whether students are still playing Harry Potter when they play a simplified arrangement?

These pieces can be useful to help band directors keep young students interested in music. A student with a fascination for Harry Potter or Star Trek will possibly see the benefit of ensemble playing and probably appreciate the music more.

The music in films is made for an entirely different reason than concert band music. Film music underscores action beneath layers of dialogue, and it provides sound effects and even silence; it is not foreground music. Even the best, most well-crafted score is subject to its place; its purpose is to support what is on screen, not merely to drown it.

As with most forms of art there is always an exception, and in this case it is the ability of a film score to stand on its own. Listeners who pick up a complete C.D. recording of a well-made score and hear it from beginning to end know what I’m writing about.

Within the 80 minutes of a score there are high points, low points, and an unfolding story line. Scores that tell stories are good choices for a transcription for band. Although most films have an hour and a half of music, many arrangers pick certain highlighted points from the film in an arrangement, tying them together making a mini story line.

With this ability many 80-minute scores become eight-minute suites; themes from the movies become themes with developments mimicking standard forms. Even better is when arrangers take entire cues from a score and transcribe them for band. Many of these cues are small pieces in themselves.

All aspects of music can allow for this. Many of Beethoven’s symphonies and piano sonatas have movements that survive on their own. Many arrangements feature overtures or ballet suites presented in a near original form, so that students play music as written closely to the hand of the original work. Film composers studied the same music and took the same orchestration classes as other serious composers, so there is no doubt that they know how to write well for individual instruments.

There are some elements band directors should watch for when picking film music for performance. These include understanding how music in a film begins and what elements dictate its direction. Then there is the composer’s attitude in building unity and a sense of development in the score as well as the arranger’s interpretation of the score.

Besides the usual marches and festival pieces that most band directors are reviewing this month, many of you will have an itch to play something flashy, perhaps from a recent movie. A film score from a summer box-office hit will get the students and audiences excited, but be certain its musical quality is high and that the transcription includes some worthy lessons for students as they polish the notes.

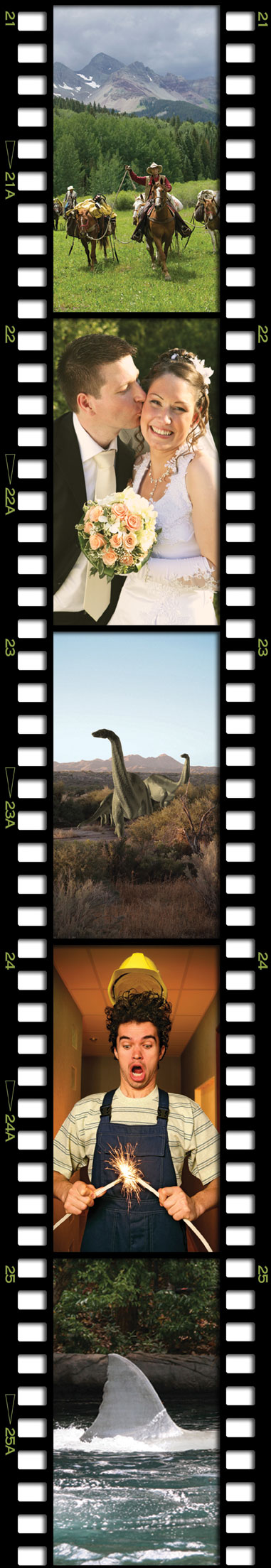

Recommended Arrangements

The Cowboys by John Williams, arr. Curnow (Warner Bros.)

The Magnificent Seven by Elmer Bernstein, arr. Phillippe (Alfred)

Jurassic Park Highlights by John Williams, arr. Lavender (Hal Leonard/ MCA)

The Wind and The Lion by Jerry Goldsmith, arr. Bocook (Hal Leonard)

Harry Potter by John Williams, arr. Story (Belwin)

Catch Me If You Can by John Williams, arr. Bocook (Hal Leonard)

Jaws by John Williams, arr. King (Edition Marc Reift)

The Pink Panther by Henry Mancini, arr. Edmunson (Alfred)

“Hymn To The Fallen” from Saving Private Ryan by John Williams. arr. Lavender (Hal Leonard)

The Great Escape March by Elmer Bernstein, arr. Smith (Alfred)

Indiana Jones March by John Williams, arr. Lavender (Hal Leonard)

Dinosaur by James Newton Howard, arr. Vinson (Hal Leonard)

These movies also have good music, but the arrangements may be difficult to find or permanently out of print:

Gremlins by Jerry Goldsmith, arr. Curnow (Hal Leonard)

North By Northwest by Bernard Herrmann, arr. Kinyon (Alfred)

Psycho by Bernard Herrmann, arr. Bocook (Hal Leonard)

How The West Was Won by Alfred Newman, arr. Higgins (Hal Leonard)

Back To The Future Medley by Alan Silvestri, arr. Sweeney (Hal Leonard)

Lawrence of Arabia by Maurice Jarre, arr. Mortimer (Edition Marc Reift)

Spellbound by Miklos Rozsa, arr. Bennett (Chappel Music Co.)

Citizen Kane by Bernard Herrmann (Bourne Co.)