Every year at Mark Keppel High School in Alhambra, California, Orchestra Camp occurs the week before the new school year. In reflecting and planning for camp, we identified improved intonation as a primary goal for the year. An internet search quickly uncovered the key concept on which to build this project: audiation. From the work of Edwin E. Gordon (1977), audiation is the ability to hear and comprehend sound without actually playing or singing it. Michael E. Martin, in his article 14 Steps Toward Improved Intonation (www.stringsmagazine.com) reiterated the importance of audiation: “Good intonation comes primarily from inside the player’s head.”

We wanted our students to develop their internal ear so they could play better in tune with more confidence and increase their ability to anticipate how music notation would sound prior to actually playing it. We took to heart three of Martin’s steps: “Sing everything before you play; always audiate what you are going to perform before you perform it; and develop a vocabulary of scales and tonal patterns that you can sing, play and recognize.” Accordingly, we developed a simple strategy, TSP (think, sing, play), to introduce to our students in camp that year.

On day one of Orchestra Camp, we introduced the students to their new vocabulary word, audiation, and explained how it could help us play more in tune. We began with the D major scale. Students notated the scale on the board, filled in the solfege syllables, we internally sang the syllables, sang the syllables aloud, and finally played the scale.

Next, the students worked in sectionals (upper strings, low strings, winds and percussion). Each group worked from a book or chorales. We used chorales in the key of D for the first days of camp and then other keys, such as G and A for the strings and Bb and Eb for the winds. For each daily chorale, we practiced thinking each part, one at a time (soprano, alto, tenor, bass); singing each part; singing two (SA), three (SAT), and four parts (SATB) together; playing each part; and then playing the four parts together. At the conclusion of sectionals, students came back together and played their chorales for each other.

Gradually we introduced the hand symbols for each solfege syllable, the chromatic scale in solfege, and the harmonic minor scale. In each case, we followed the same process of thinking, singing, and playing. During camp we also wrote simple melodic phrases on the board for students to read using solfege, such as Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star and Jingle Bells. The process became second nature by the end of camp. As the school year started, we transferred the strategy of TSP to their concert repertoire.

We reinforced the concept of audiation and the strategy of looking thoughtfully at the musical notation, singing it mentally and out loud, and only then playing it. As we progressed through a challenging fall semester, preparing and performing the musical A Christmas Carol, we maintained daily warmup exercises in solfege, always thinking, singing, and playing the exercises. Lee continued the process as the students learned the spring concert repertoire. As an added incentive to apply their new knowledge of solfege and the TSP strategy, Bartlett composed a piece for the Orchestra, aptly entitled Solfeggiana. Capitalizing on their abilities to sing solfege, the piece requires students to sing brief sections, and even to play and sing simultaneously. Lee sustained the TSP strategy throughout their learning of the piece, breaking into instrumental sections to write in the solfege syllables and practice singing.

Getting instrumentalists to sing may be a challenge. If your students are anything like ours, you will hear comments like “This isn’t a choir” or “We signed up for orchestra.” It’s not that students dislike singing, but they probably have rarely done it outside the comfort of the shower or bedroom. Singing in public can be intimidating for many; establishing the music room as a place where mistakes are encouraged and where students feel safe and free of judgment is crucial to getting students to sing. Singing in a band or orchestra is not only a great stepping stone for teaching more music theory; it is an easy way of getting your kids to play in tune while building their self-confidence.

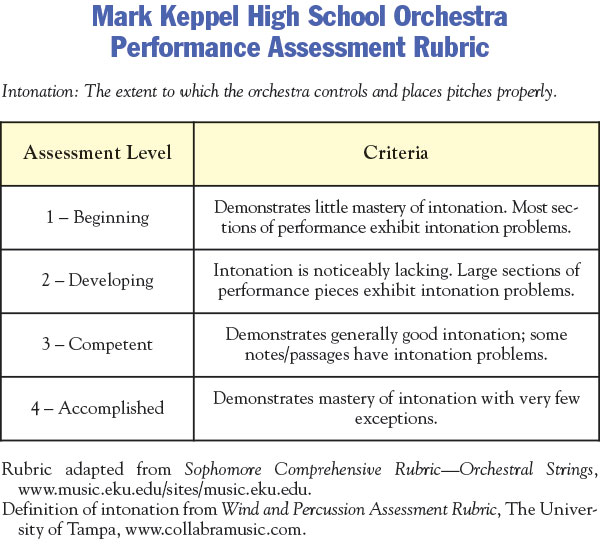

To evaluate the outcomes of our audition project, we asked three music teacher colleagues not associated with our school or district to listen to the first five minutes of the orchestra’s spring concert performances, one from April 2016, the second from April 2017. We asked them to rate the intonation of the group using a simple rubric. Two of the three rated the orchestra’s intonation better (from 2 to 3) the year of the solfege project, and one rated the intonation the same for both years. We conclude from our project that the time spent on teaching and reviewing solfege through daily practice seems to increase students’ ability to audiate, resulting in more confident playing and better intonation. The experiment continues as we carry the project forward into the new school year.

Resources

Learning Sequence and Patterns in Music by Edwin E. Goodwin (Chicago: G.I.A. Publications, 1977).

14 Steps Toward Improved Intonation: Solo and Group Exercises from Author and Instructor Michael E. Martin, posted by James Reel, from Stringsmagazine.com.

Bach and Before for Strings by David Newell (Neil A. Kjos Music Company, 2005).

Bach and Before for Band by David Newell (Neil A. Kjos Music Company, 2002).

Download a free copy of Solfeggiana at truluckmusic.com Enter code 2017SOL.