Dan Wilson is director of bands and music specialist for the Frankfort-Elberta Area Schools in Frankfort, Michigan, a position he took after retiring from a career in education in Georgia. “I grew up in Clayton County, Georgia, which from the 1960s to the mid-1990s was a hotbed of school bands. In the heyday of that county’s program, there was someone going to the Midwest every year. I graduated from that band program, and that was where I spend almost all of my band directing years in Georgia. I remained in or near the area during my first career as both a teacher and administrator.” On his choice to continue teaching, Wilson says, “I wanted to teach some more after spending the last years of my career in Georgia in administration. Before I got to Frankfort, the program had gone through a couple of lean years after having a string of successes, so it was a situation where I could rebuild and exactly what I was looking for.”

Dan Wilson is director of bands and music specialist for the Frankfort-Elberta Area Schools in Frankfort, Michigan, a position he took after retiring from a career in education in Georgia. “I grew up in Clayton County, Georgia, which from the 1960s to the mid-1990s was a hotbed of school bands. In the heyday of that county’s program, there was someone going to the Midwest every year. I graduated from that band program, and that was where I spend almost all of my band directing years in Georgia. I remained in or near the area during my first career as both a teacher and administrator.” On his choice to continue teaching, Wilson says, “I wanted to teach some more after spending the last years of my career in Georgia in administration. Before I got to Frankfort, the program had gone through a couple of lean years after having a string of successes, so it was a situation where I could rebuild and exactly what I was looking for.”

Wilson teaches general music to lower elementary grades and instrumental music in grades 5-12. “This is completely different from an Atlanta-area district where there are so many students that there is no opportunity to establish much of a relationship with any of them. The total enrollment in my district is 560 students. We have two campuses, an elementary campus that is K-6 and junior/senior high campus that is 7-12. I spend half the day teaching elementary music, and afternoons I teach band from fifth through twelfth grade. There is a high school band and a junior high band consisting of seventh and eighth graders; I see each for 53 minutes daily. The fifth- and sixth-grade bands come on alternating days.”

The desire for a second career is not uncommon, but what led you to choose such a different environment?

Many people wonder how I ended up in Michigan and ask if I put on a blindfold and threw a dart at a map. My wife and I were both tired of big city sprawl, traffic, and problems. I wanted a small school in a little town where I could get to know all the students and their families, and I had a long-time friend in Michigan. My best friend growing up in Georgia was named Mike Eagan. He and I played horn in the same junior high and high school bands, both majored in music at the same junior college and both transferred to the same university. We got our teaching certificates at roughly the same time and ended up teaching in the same small town in Georgia for five or six years. During that time he was working on a master’s degree at VanderCook, and he met the band director at Manistee High School in Michigan. They got married, and he currently teaches at Benzie Central High School, which is seven miles from me. It has all come full circle; Mike and I are teaching in the same county again, just as we did in the 1980s, except 1,000 miles north.

How were the first years of rebuilding the program at Frankfort?

Many of the high school students had dropped out of band before I got there, so I had a chamber ensemble the first couple years. At various times during my career in Georgia I had had small bands. After I had spent a couple years teaching at a middle school, the district opened a second middle school almost right in our back yard and took a huge portion of the school population. It decimated the band program for a year or two until we were able to recover from the numbers loss, but I took a band of 19 eighth graders to a festival and got a first division rating. This alleviated some of the initial terror, but it was still daunting to see the instrumentation I had in the first high school band class.

That first year, I had two flutes, two clarinets, an all-star caliber alto saxophonist, a bass clarinet, and a contrabass clarinet. The only brass player was one trombonist. There were also four percussionists and a violinist. There were many split rehearsals. I sent the percussionists to a practice room with percussion ensemble music and then arranged chamber music for everyone else. I would work with each group for a while and go back and forth.

I did a substantial amount of editing, rewriting, and arranging to make music work with that instrumentation. The way to arrange for odd instrumentation depends on the situation. It is a bit like a puzzle. Try to make a score work with the pieces you have while keeping the integrity of the harmonic structure as much as possible. For our Christmas concert, I took some simple, straightforward, grade 2 full band arrangements, sat down with the score, and figured out what I could rescore without changing the harmonic structure. On the spring concert, we played a watered-down arrangement of An Italian in Algiers. That alto sax player was perhaps the best one I’ve seen in my career, so I gave him all the oboe solos, which made him happy. One of the percussionists was a good mallet player, and we have a marimba, so she doubled and rolled chords on the marimba quite a bit to fill out chord structures. It turned out to be a good arrangement for that group. The high schoolers who were still in band when I started were great students, willing to do what I asked to make it work. Instead of going to band festival that year, we entered the chamber wind ensemble and the percussion ensemble in the solo and ensemble festival. Both groups received a first-division rating, which not only made the students feel good, but also laid the foundation for what we have done here.

The high school band is still small by most standards. There are almost 30 students, but the instrumentation is outstanding for that size. The high school band has four flutes, two clarinets, four alto saxes, a tenor sax, a bass clarinet, a contrabass clarinet, two trumpets, a horn, four trombones, a baritone, a tuba, and four percussion. We do not march but have a pep band in the bleachers at home football games. In small schools, many students are involved in multiple activities. My first trumpet player wants to be a music major, but she is also in drama club and volleyball, and some of the boys in the band are on the football team and wouldn’t be able to march anyway. The pep band is a mix of junior high and high school students together. I wrote a set of easy arrangements that we use in the stands. The junior high students can play them with a bit of work at the beginning of the year, and the high schoolers know many of them in their sleep.

In addition, it would be impossible to run a summer marching band camp here. Many students have jobs in the summer because tourism is a big industry up here on the coast of Lake Michigan, and by Michigan law, we cannot start school until after Labor Day. The weather starts turning cold and rainy and then cold and snowy quickly up here. In Georgia, October is the month of the big marching band contests, and every weekend there are multiple competitions. By the end of October in northern Michigan, you don’t want to be outside.

What are the keys to building a strong foundation in beginning band?

We work hard in the band classes. I only see the elementary students every other day for band, but when I have them it is for 55 minutes from 2:10 to 3:05. My primary concern is tone quality, and embouchure development comes with this. Young teachers frequently get caught up in technical development and try to accomplish a set number of pages in the beginning band book by the end of the year, but this is putting the cart before the horse. If students sound bad, it doesn’t matter how many notes and fingerings they learn; technical skill cannot cover bad sound. If students have a correct embouchure and good basic sound, that will pay huge dividends down the road. Students will develop technique as they get older. If they sound good and develop a characteristic tone, meaning their pitch center is pretty close to where it ought to be, then you will not have to waste a lot of time going up and down the rows with a tuner.

Second to tone quality is rhythm reading. We read a lot of rhythm patterns. One thing I see frequently is carelessness with long note values. Students think, “Oh good, this is an easy note,” and fail to consider exactly how long it is supposed to last. There are dozens of rhythm pattern books out there, so just pick one at the appropriate level. I do not ignore other aspects of musicianship; if you practice scales every day and are doing the right things in class, that will take care of itself.

Because of the long rehearsal time I have the luxury of having students play individually and will check tone quality by listening to the first few notes when they are beginners and later a scale or line out of the book. We do a lot of individual playing, so students become accustomed to that early. The rehearsal length necessitates a variety of activities, otherwise students’ faces would fall off; there’s no way first- and second-year players can play for that long. They haven’t built the stamina yet.

Individual playing time typically takes 15-20 minutes but can last a bit longer if someone has an embouchure problem or is working on a new snare rudiment. From there we go into method books and always start with a review of what we’ve already done. With the fifth graders, all year long we start with the first page of the book, and I pick a couple lines off of each page that we have previously done as a review of the concepts. After that we tackle whatever I had assigned students for that day’s lesson and push ahead. By that time we are near the end of the class period.

I also spend a little bit of time with percussion at the beginning of class. Their individual playing is on snare drum at first, and we work out of a separate snare drum technique book from the rest of the class. They focus on rudiments, long rolls, and other basic snare technique. During the last part of the hour, they play with the rest of the class, but working out of bell books. They play on their bell kits the same songs as the wind players are playing.

What is your approach to sightreading?

When the high school instrumentation fleshed out and we had a full band again I started taking them to district band festivals; high schoolers do quite a bit of sightreading in the fall in preparation for this. After we warm up I pass out a piece, and we read it before we get into the music I have scheduled for that day. I have not taken the junior high band to festival yet, although we have a mock festival. We prepare a festival program at the same time high schoolers prepare theirs. One afternoon the junior high band stays after school while I invite someone to judge and give them an informal evaluation so they get a taste of the festival experience. As soon as we finish that, we start working on spring concert music, and at this point junior high students work hard on sightreading. Eighth graders spend almost an entire year on sightreading, in spring as eighth graders and again that fall as freshmen.

What advice would you give to a new teacher who is assigned elementary music classes?

I went to college in the 1970s. I had one quarter of elementary music when earning my undergraduate degree, that is long since forgotten, and everything in music education is different now. My advice for anybody who gets a job teaching general music is to talk to other people who teach it. I was fortunate to have a long list of people back in Georgia I could ask for advice. The nice part about general music is that once the curriculum is set, you can roll much of it over from year to year with only minor tweaks. This year’s third graders will learn the fourth grade curriculum next year.

Much of what I do is designed to benefit the students who will join band in fifth grade. Early in my career, the largest elementary that fed the middle school where I taught had a tremendous general music teacher, and she taught rhythm to her students. I could see the difference with her students, who had been working on rhythm for years by the time they got to me. We do quite a bit of rhythm preparation. I have kindergarteners and first graders march every day to get them to feel the beat of the music. The ability to feel the pulse is the beginning of everything. It is sad when a student wants to be a musician but cannot feel the beat.

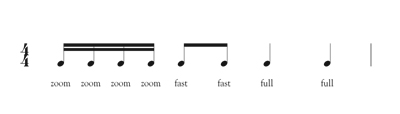

We also get into some very basic notation. I use different note names because young children cannot understand fractional relationships well. A half note is called a hold, and a quarter note is a full note because it lasts for a full beat. That helps students get over the habit of confusing eighth and quarter notes, which is a common rhythm mistake. Eighth notes are fast notes, because they are faster than the full beat notes, and by second or third grade, we get into 16th notes, which are zoom notes. By fourth grade, students would be able to read rhythms, calling the notes by those names and saying patterns accurately.

What did being a band director teach you about being an administrator?

If you are an effective band director, you are developing many of the tools necessary to be a good administrator. This includes developing relationships with both students and parents, building a band booster club, handling finances, raising money, spending money to acquire equipment and music that will benefit your program, and developing your curriculum. Music teachers already do these things, and they are some of the same skills administrators use. Organizational skills are important.

The only surprise was the difficult home situations of some of the students who were sent to my office the most frequently. Eventually, things get to the point at which you talk to some parents on a daily basis, and sometimes you wonder how some students turned out as well as they did. It was a bit surprising moving from the city to a small town; I would have thought some of the horror stories seen in children’s lives in Atlanta would not be replicated in this area, but I imagine it is the same all over the country. Some students are trying to handle difficult situations at home, and some of them amazingly come through it with flying colors. I am more aware of that now than I was in my early years of teaching.

What are the typical duties of an administrator?

This varies widely. My first administrative job was as a fine arts curriculum coordinator in an adjacent county, where some of the band programs were beginning to develop, copying what had happened in Clayton County. They started fleshing out administrative staff, and that position became available as I was finishing my administrative certification, so they hired me on. They were in a big curriculum writing project at that time, so I came in towards the last third of the project and helped put the finishing touches on the fine arts curriculum for the district. They were also in the process of starting up a performing arts center, and we helped get that building up and running. I tried to get out to the schools as much as I could, but evaluation of the fine arts teachers was up to the principals; I was just there for support to provide what help I could.

From this I went to my only school-level administrative position, which was as the assistant principal at a rather large middle school. My duties included such administrative tasks as keeping the lunch line in order and helping with dismissal. Discipline was a substantial part of the job, and I was also in charge of standardized testing materials, making sure that they arrived and were in order, that everything was distributed to the teachers, and then collecting everything after the testing. This was just bean counting, but it was an important part of what we do because of the emphasis placed on standardized testing now. I was also the administrator in charge of evaluations for the sixth grade teachers and part of the seventh grade staff.

My final administrative position was as the building administrator for the Clayton County Schools Performing Arts Center. It is a beautiful building with a maximum seating capacity of 1800. The seating areas in the back of the hall on both sides were on two giant turntables and can rotate around to form seating for two smaller halls. Walls behind the seats closed everything off. The building had the capacity for three simultaneous performances, or we could open the turntables and make one big concert hall seating 1800. The district was the seventh-largest in the state of Georgia at the time I retired, and the building was nearly always in use. If the schools didn’t need it, we rented it out to community groups.

What advice would you offer teachers about the best way to work with administrators?

The key to working with administrators is communication. Try to keep an open line of communication. Part of that is building a relationship. If the administrator isn’t on the telephone or busy with somebody when you arrive, make it a point to say good morning. Administrators know who is doing their job and working hard, partly because there won’t be line of students from these teachers waiting to get into his office for disciplinary reasons. Open lines of communication make it a lot easier when it comes time to request funds or need help with a particular situation.

What advice would you offer new teachers?

The most important thing for a new teacher to do is be careful not to become an island. Find somebody you can ask questions. Because of the uniqueness of each situation, there will be something you are unprepared for or some unanticipated problem. Have people you can call and get answers from. I was lucky to grow up in a strong environment, but not a competitive one. Any of the band directors in that area were happy to answer any questions; there was never competitiveness, only a desire to help each other out. The camaraderie was what kept the high level of performance in Clayton County going for decades, because any time a new director came in he had an instant circle of people he could ask any question, whether brilliant or dumb, and get useful information. Have people you can ask questions, because you will have a list of them quickly.

Be prepared for the investment of time required, particularly in a small school. You will have to spend some time editing music for small groups and making arrangements work with limited instrumentation. College students should take all the arranging classes they can find. Many young teachers do not realize that limited instrumentation is not an excuse at band festivals. If you don’t have a horn, but there is an important line, cover it with another instrument.

Ignore the grass-is-always-greener urge. If you are lucky enough as a band director to be in a place where you enjoy your job most days, the community and administration supports you, and the students respond to you and your teaching, think long and hard before changing positions. There are a couple of jobs that I left voluntarily in Georgia before I should have because the grass looked greener elsewhere. I try to cherish each day now in Frankfort. The old cliché is true: life is short, and teaching careers are even shorter. Finding a good situation to teach in is a stroke of good fortune, so do not be quick to abandon it. After all, there are no perfect positions out there, no matter how hard you look or how many times you change jobs.

I wish I had been more flexible toward people and situations. It is okay to be rigid on musical matters – a wrong note is wrong, being out-of-tune is wrong, playing in a rest is wrong – but the old-school band director was harsh and rigid on everything, not on just the musical aspects. I am much more flexible and tolerant on non-musical matters this time around, so much so that my wife is often amazed when she is around my bands.

If a band is functioning the way it should, the director gets back more than he gives. My trumpet player who wants to be a music major was a sixth grader when I started here, so I’ve gotten to watch her develop as a musician. I also have a freshman saying she wants to be a music teacher. This has been a great way to cap off a career that started at a fabulous situation in Clayton County, Georgia.

Dan Wilson is a native of Atlanta, Georgia and earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in music education from Georgia State University as well as a specialist degree in educational leadership from the University of Southern Mississippi. Prior to his second career in Michigan, Wilson was a school band director in Georgia for two decades followed by various positions in public school administration until his retirement from Georgia in 2006. During his more than 30 years in music education, he has worked with all ages, teaching music to kindergarten children through college undergraduates and supervising teachers during his years as an administrator. As a band director, Wilson’s bands have earned numerous honors, including invitations to perform at state, regional, and national music education conferences.