In my April 2014 article in The Instrumentalist (Five Aspects of Great Musicianship), I highlighted a section on musical style. The more I thought about that article and the farther into spring our groups rehearsed, we found ourselves needing more clarity on how to define and align a style throughout the ensembles. Out of this was born a style manual for our program. Our manual doesn’t fit perfectly for every piece we program, but it provides a valuable launching point for discussions with the ensemble about note starts, shapes, and lengths.

As we gathered our thoughts we looked back at one of the finest chapters ever written for band pedagogy, W. Francis McBeth’s Effective Performance of Band Music (1972) where he refers to Solution II. For this chapter McBeth interviewed several famous composers and asked each how they would interpret several style and articulation indicators for their own music. The similarities and notable differences shared amongst several of the 20th century’s most prolific composers, are fascinating. We began with McBeth’s Solution II for the genesis of the style manual for our developing ensembles. We sought to align a set of note starts, values, articulation weights, and style indicators that could serve as a foundation when learning a new work. For ease of discussion, most of the style and articulation indicators we work with in our developing ensembles begin with shapes (mostly simple blocks) and permutations of that shape.

The Anatomy of a Note

As we consider articulation, weight, and style, we first separate each note into three parts: the front (articulation), middle (shape), and the back of the note (value/release).

The Front of the Note/Articulation

In an attempt to simplify our ideas on musical style and indicators, we feel that there are three prime possibilities for how we treat the fronts of notes. Some notes start at the exact volume and strength indicated by the composer. So, if the composer has indicated forte for the clarinets, the note begins at forte with a focused articulation syllable.

The use of the articulation syllable can be a matter of personal preference – too, taah, daa, teeh, too, etc. While we work diligently to align each section with the same syllable, we can often find slight exceptions to the rule as we move down the line from player to player. With syllables, we try to move toward center; we want the saxophones to sound the same when they start their G. About 90% of students can use the same syllable and achieve the same sound, but some require a slightly firmer placement (we use the phrase “more taste buds on the reed”), while another student with quite a bit of orthodontic work might require a different approach. Ultimately, we have to trust our ears to identify a note start that is in tune, in time, and in volume.

Once we have identified the standard, unaccented note start, we begin to listen to note starts that require a stronger start than the middle and back of the note will resonate. These notes are usually accompanied by an accent indicator. We advocate producing these notes with more air and not more tongue. If forte air would be required to start the note in the phrase at an unaccented level, then this may simply indicate a forte-plus start. If we’re looking for a very pronounced start, we may ask students to produce a note start one full dynamic above the written dynamic of the phrase.

Finally, there are a few notes that start quite softly and fade up to the level of the middle/body and back of the note. These are seen much less than the aforementioned two, but we teach that these notes should start with a fast but small stream of air. The easiest analogy is that of straws at a fast food restaurant. We find that a milkshake straw-sized air column works for fortissimo playing with open, sustained sounds. The soda straw-sized air column applies well to typical forte playing and is the most used. The tiny coffee stirrer straw applies to a quick but quiet note start. It is seldom used but works with staggered breathing passages and notes that start from niente.

Middle of the Note/Shape

Second, we consider how we treat the middle/body of the note. For the vast majority of notes, there are no perceptible changes to the middles of notes. At times we may have to play a crescendo or diminuendo, but these alterations are the exception rather than the rule. We want students to play the middle of the note with a good, characteristic sound, and, if sustained, the note should remain in tune with a good tone.

With developing ensembles, we often find a tendency for the middle of the note to decrescendo. It is important that students sustain note volume from front to back without any variation. If some students were edging the note louder, we would stop the ensemble and make a correction. However, we often find that when students fade down into the sound with a decrescendo, we have to hunt for the reason that the ensemble sound has lost a bit of quality. This is most noticeable in lower split parts for instruments like clarinet and trumpet. Often, the initial quality of a chord is quite solid, but because the middle of the note loses energy and volume in the seconds and thirds, we find that the chord quality can change or become blurry as it is sustained. We encourage a block-shaped sound, unless otherwise indicated. If certain students continually fade their volume down to the backs of notes, encourage them to draw a rectangle over the note as a reminder.

The Back of the Note/Value/Style

Last, we address the back of the note, often called note value or style. While composers often indicate a style preference on certain notes, the determination of the incremental amount of silence between each pitch is often made based on the type of piece being performed. We have found that a general approach is better than none at all.

In the past we leaned on terms like march style for a light, lifted backside to notes with a little bit of space. A work marked staccatissimo might have a very short note value. A piece labeled cantabile would be performed in a longer and more connected style. With all of the possible variations for the ends of notes, we spend the majority of our time aligning the backs of notes. With persistence, the fronts of notes will align once a piece has been learned and added to muscle memory. The back of a note takes a sensitive ear and a tremendous amount of time to perfect.

The Style Manual in Practice

Once we determine our norms for the fronts, middles, and backs of notes, we venture into more specific examples and ideas about shape and design.

The Unmarked Note

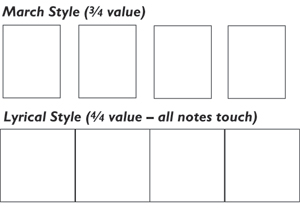

Before beginning a new work, we assign a value to the unmarked note. We often derive these values from a block form. We begin marches with a lighter, more lifted style, while a more lyrical work will employ notes that touch. When preparing to sightread a work, we often perform an F major scale, descending in quarter notes or eighth notes in the style of the piece. This helps students develop an idea of how their air flow will feel when performing the new work. Here are two examples of how we might explain the style of a work:

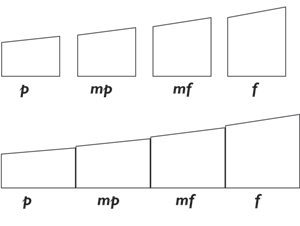

In addition, with the unmarked note we can sketch crescendo and diminuendo exercises. We do not advocate the extreme shaping of individual notes, unless they are full-measure values. So, for instance, in a work with a crescendo from piano to forte over four beats in quarter notes, we advocate that students perform as follows:

The Accent

Accents are among the most frequently used articulation and style indicators by modern composers. In thinking about McBeth’s interviews, it is interesting to note how such composers as John Barnes Chance and Frank Erickson felt this indicator only affected the note and cautioned that it should not shorten the value of accented pitches. On the contrary, Howard Hanson and Martin Mailman offered that it not only affects the front of the note, changing the articulation, but also the back of the note, affecting the style.

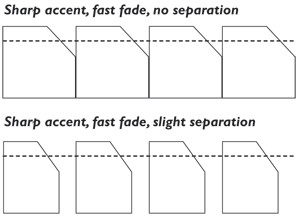

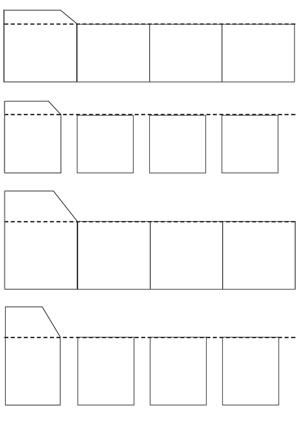

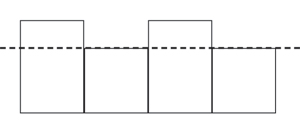

The best way to define accents is by offering performers a set of block shapes that show the sharpness of the accent, how pointed the note will be and how rapidly it softens. We can also set up several blocks in a row to demonstrate how the ends of each note are affected in relation to the pulse between clicks of the metronome. The dotted line represents the existing dynamic level for the phrase:

.jpg)

We sometimes indicate what an accented pitch would look like amidst a measure of unmarked notes:

Staccato

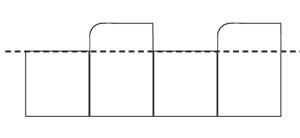

We next move to the staccato indicator and stress that staccato markings have no effect on the front or middle of the note. Staccato changes the back of the note, making it detached, light, or lifted. To clarify the exact length of the staccato, we often talk with students about a visual image of positive space versus negative space. We ask them to think about how wood fences are constructed. In the neighborhoods around our school, there are three types of fences that we see. There are board on board fences that allow no light to pass through. This is analogous to a lyrical or singing work. Next, there are standard fences where the boards nearly touch but a small amount of light passes through. This is comparable to a slightly detached musical line. Finally we talk about traditional picket fences that illustrate exactly the staccato sound with near perfect gaps between the notes. This analogy helps us play with a light, lifted, crisp, and detached style.

If students perceive the staccato indicator as a dot under the note that morphs the note into half sound and half silence, unlike the dot aside the note that adds half value, we find they are more likely to remember what this style indicator should resemble in most cases.

Additionally, in talking about staccato (one of the hardest sounds for us to align), we often refer to pizza, as this analogy is easy to discuss in terms of fractions. Staccato indicates half of a pizza, and since there are no half-pizza boxes, the half-pizza must be placed in a whole pizza box. On the side of the box where there is no pizza, there is only air. This helps explain the concept to our younger students.

Tenuto

The tenuto is the most misunderstood of the articulation/style indicators, perhaps because it is, in many respects, the opposite of the accent. Many composers use the tenuto to indicate a gentle note-start (Vincent Persichetti put it best when he wrote “gloved pulsation”). However, in recent years, composers are moving the tenuto more towards the idea of a stress-weight indicator, just as Hindemith and Nelhybel used it years ago. When our groups prepare pieces by Donald Grantham, Frank Ticheli, and John Mackey, we have found that the tenuto sounds best as a stress-weight indicator. As a result, when drawing the shape, we often surround it with standard value notes, thus indicating its height in the sonic sentence.

In addition, we will sometimes round the edges of the tenuto to indicate that it doesn’t have a hard, right angle note start. We avoid using the word attack for this reason.

Marcato

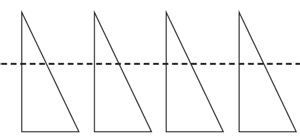

The marcato indicator is, in our style manual, a composer’s request for additional volume on the front of the note and shortened value on the back of the note. we tell students that if we added the accent and the staccato, we would likely arrive at the marcato. In drawing shapes for the marcato, we show tall, pointed staccato marks with right triangles.

For an analogy, we discuss adding marcato like marking a player in soccer. if the opposing team is throwing the ball in or executing a corner kick, we are each assigned a player to mark on the field. Now, to avoid a penalty, we don’t want to tackle the player or note but just want to bump them. It is a hard bump, but not sustained effort on our part. It is quick to avoid the official but abrupt enough to keep the player moving.

Combinations

After defining values for the unmarked note, the staccato, the tenuto, and the marcato, we discuss any combinations that arise. We sometimes struggle with the combined tenuto-staccato or the accent-tenuto; each has a set of mind-boggling possibilities for developing players. When we use simple shape addition with our style manual, we arrive at something that is agreeable to begin developing the work.

Conclusion

The style manual has evolved over time. There will never be a true system that outlines every style indicator and every articulation for all music. With careful study, we can help students learn a system that works for preparing pieces for concerts and the sightreading room. We hope they can back up their style decisions with musically literate opinions as well as visual images that represent the idea best in their minds.