In the past students were surrounded by jazz on the radio, at dance halls, and in record stores. They listened to favorite players and imitated their music by ear. At jam sessions ideas about harmony and technique were shared among players and practiced on the spot. Many of the tunes called at these sessions were familiar popular songs that people had little difficulty memorizing.

In the past students were surrounded by jazz on the radio, at dance halls, and in record stores. They listened to favorite players and imitated their music by ear. At jam sessions ideas about harmony and technique were shared among players and practiced on the spot. Many of the tunes called at these sessions were familiar popular songs that people had little difficulty memorizing.

Students can learn much from these techniques. Jazz is an aural tradition, and the phrasing and style of famous musicians can only be learned by listening to their recordings. In addition, playing at jam sessions helps students learn and develop performance ideas. Memorization permits group members to have more eye contact and ensures that the melody and chord changes are known well enough for soloists to be creative within the structure of a piece.

Most jazz musicians improvise using the skills they have already acquired. Few performers are able to play completely out of their comfort zone, and those that do can only make it work for a limited time or a specifically planned idea. The goal of practicing is to expand the tools available for use when improvising. Although many technique-building exercises involve limited improvisation, it is important to stay focused on the specified task and avoid confusing this type of practice with a creative artistic statement used during a performance..jpg)

This can be compared to a sport, in which exercises and scrimmages are distinct elements of a practice session and are not mixed. Many of a sport’s exercises mimic elements of the game; a scrimmage is the place to test the full range of skill with additional variables. In jazz, a jam session is the musical equivalent of a scrimmage where players can test the skills they practiced through the week in a more complex situation. Although some harmonic language and rhythmic ideas are only found in certain styles of jazz, these practice methods will be beneficial for all styles.

Technique

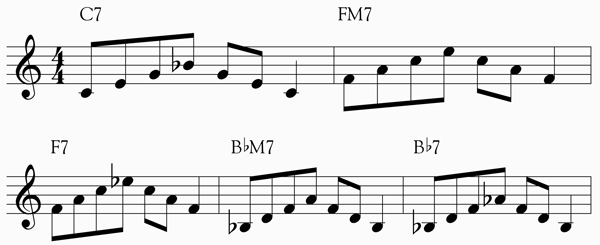

Technique includes scales, arpeggios, progressions, and technical exercises. Consistent practice of scales should include the use of different patterns:

.jpg)

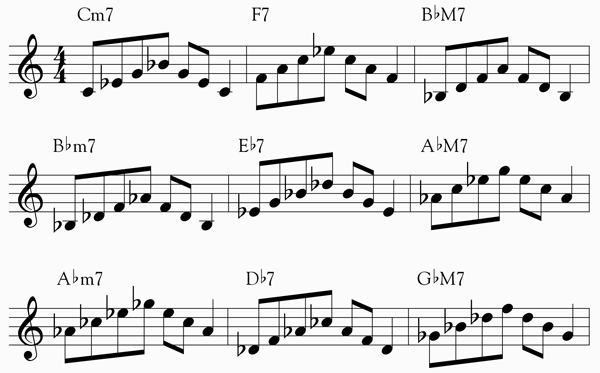

Technique is built by memorizing major, minor, and dominant chord types including 7th and 9th scale degrees. Begin by learning the dominant arpeggios around the circle of fourths.

.jpg)

When these are mastered, study the major 7th arpeggios in the same way. Incorporate each together using the circle of fourths as follows:

When the major 7ths are mastered, move on to the minors. These three chord types comprise the majority of chords used and should be mastered completely. The following pattern is referred to as the downstep progression and is common in many jazz tunes. By moving from B-flat M7 to B-flat m7, students can transition to A flat by considering the B-flat m7 the ii of that key. This pattern can be continued through six keys; it will take a half-step shift to practice the other six keys.

Additional patterns used in chord progressions include motion by step, chromatically, and by minor third. Practice chords on these to become familiar with the sound of each progression.

Language

The study of the language of jazz includes learning licks and stylistic devices as well as ideas about articulation and the concept of swing style. Licks and turns of phrase that are commonly used by musicians give solos an authentic sound and provide a link to certain styles or players. Many of these ideas are learned through studying transcriptions or by transcribing solos from recordings. Excellent resources for written transcriptions include Artist Transcriptions (Hal Leonard), Giants of Jazz (Warner Bros.), and the Charlie Parker Omnibook (Jamey Aebersold). However, because jazz is an aural language, study of a transcription begins by listening to the recording many times. Many written transcriptions are not entirely accurate or purposefully exclude articulations. In addition, written music cannot duplicate the subtle rhythmic and articulation variations musicians use.

Begin working with a written transcription by listening to the music and marking in articulations and rhythms that require clarification. Learn the technique of the solo slowly and work for accuracy without the recording. When the solo can be played at the original tempo, play along with the recording and mimic all the elements of the original.

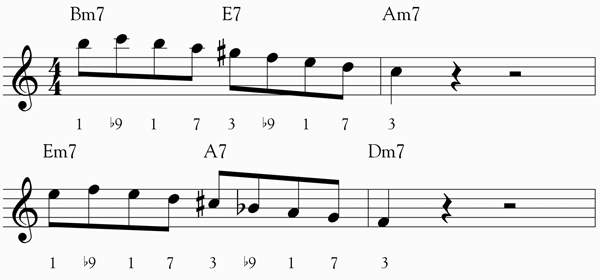

Add licks to your repertoire by choosing ideas from a learned solo that are appealing or sound particularly jazz-like. Analyze these to find out what type of chord or progression they fit over, then learn to play them in all keys. The easiest way to transpose a lick is to determine the scale degree of each note against the base note of the chord before transferring it to the next key.

An easy way to link these ideas to your improvisation is to add one new note at the beginning, the end, or both. Play the idea in the appropriate progression over a play-along method such as The ii-V-I Progression by Jamey Aebersold or The Ramon Ricker Improvisation Series: Volume III: The II-V-I Progression, Standard Tunes and Rhythm Changes by Ramon Ricker. When the idea is comfortable, play it repeatedly at the same part of a tune to incorporate the rhythm and technique of the idea as part of a true improvisation. Don’t forget to determine if there are other harmonic applications for an idea.

Master one lick before moving on to a new idea or more complex variation. The only way to be certain that an idea can be played cleanly and effectively every time is to incorporate it fully as a technique and have it entirely memorized. It may be necessary to break down a difficult scale or lick into manageable steps before putting the whole thing together.

A standard should be set determining when something new can be added to an improvisation. For example, a scale or arpeggio may need to be memorized and playable in 16th notes at quarter = 120 before it can be used. It is also important to understand how an idea can be used theoretically and how it has been used historically.

Students should avoid the temptation to collect a large number of methods and recordings unless there is time to master each of them. The ultimate value of these materials is that students can absorb the information to the point that it can be used fluently during performance. Merely owning the material and having it available as a resource will not immediately make someone able to use it at will.

Tunes

Learning a tune and its standard keys permits musicians to perform together spontaneously without having rehearsed together. Refer to jazz method books or go to local jam sessions and write down the tunes that are called. Begin learning the tunes – melody and chord changes – that are performed most often. Approach improvising on a tune by adding one element at a time.

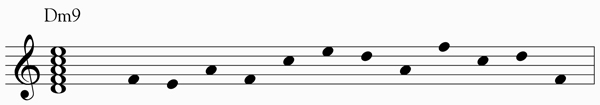

1. Learn each chord by improvising on each set of chord tones out of time. The following example shows the D-minor 9 chord and possible note combinations when playing the individual pitches of the chord. Eventually, students should be able to know the pitches within each chord instantly. Because it is important to be flexible when playing the notes in

a chord, the pitches in each chord should be played in different combinations and registers.

After learning all of the chords in a tune, play with a metronome or use a play-along book to guide your practice.

2. Use guide tones to move smoothly from chord to chord. In all types of music, the most standard melodic motion between chords is to move to the closest tone in the upcoming chord. Typically the closest note will be a major or minor second away. This concept is called voice leading in music theory but applies equally in jazz styles, where it is often called using guide tones. After students learn the notes in each chord, the ability to move smoothly between chords may be the most important step toward creating convincing improvised lines.

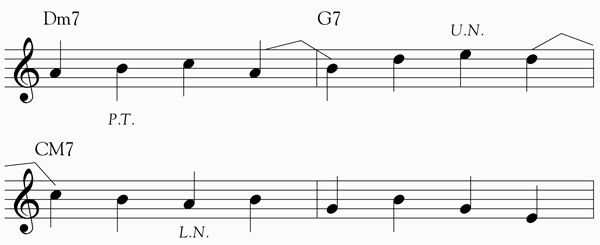

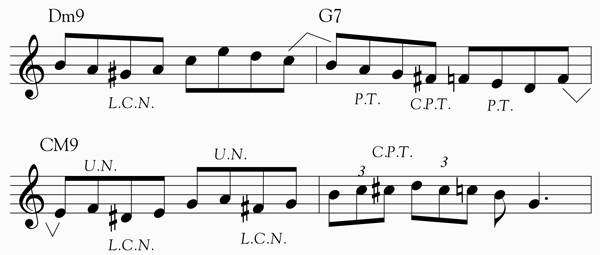

3. Incorporate neighbor and passing tones to produce smoother melodies. Using nonchord tones can create smoother melodic lines while improvising. Passing tones are nonchord tones placed between two different chord tones, and upper and lower neighbor tones are nonchord tones played above or below a chord tone followed by a return to the same chord tone.

4. Use chromatic tones to add greater dissonance and interest. Chromatic lower neighbors that move to chord tones give the perception of multiple leading tones, and using upper neighbors and chromatic lower neighbors is a common way to elaborate on chord tones in improvistion.

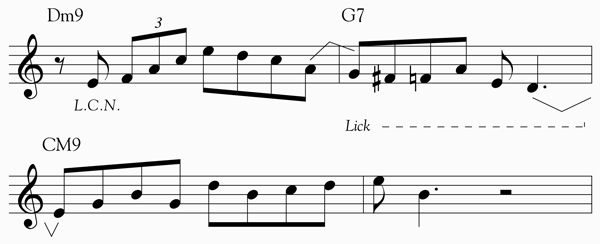

5. Incorporate licks and ideas that have been learned from transcribing. Licks are short ideas that fit in a particular progression. Often licks suggest a particular player or period in jazz. For example, a lick that Charlie Parker used frequently would be appropriate for an early bebop piece. Many jazz musicians learn multiple licks for specific time periods and players to show the style of a tune in their solos. Licks that sound generic to a particular style are a good place to start because they were likely used frequently and therefore are quickly recognizable.

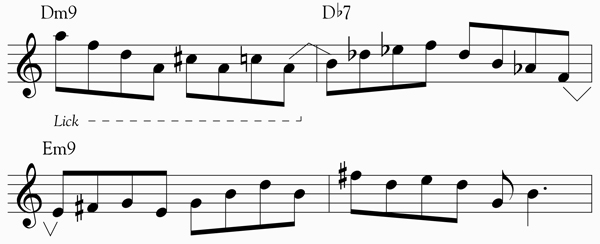

6. Explore substitutions to create more interesting sounds and extensions. There are many substitutions for each chord type; the best way to learn about them is to study jazz theory or ask jazz pianists or guitarists – these players tend to use substitutions frequently. The example demonstrates using a tritone substitution over the dominant chord (D-flat7 instead of G7) and E minor 9 instead of C major 9. For substitutions, the rhythm section can play the new chord along with the solo instrument or they can play the original chord with more open voicing to minimize harsh dissonances.

Structuring Practice

There are two ways to structure practice time to give enough attention to technique, language, and tunes. The first is to divide each practice session into equal parts. It is useful to set a timer to stay on task and change quickly to the next segment. The second is to devise a system that rotates the focus of each practice session throughout the week. For example, it may be beneficial to devote most of the first couple days of the week to a transcription project, then spend the rest of the week working on other elements.

Jazz improvisation is an ability that evolves and matures slowly over time. Long but infrequent practice sessions make it impossible for students to memorize tunes and phrases to the point that they can recall them instantly during performance, but consistent, dedicated practice and commitment will be rewarded with improved ability and a greater understanding of jazz.