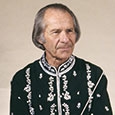

Despite his passing in 2004, Frederick Fennell remains one of the essential voices in our field. Decades after his articles were published in The Instrumentalist, his observations remain just as charming and wise. In this classic from 1986, he warmly recalls his early musical development at Interlochen and Eastman.

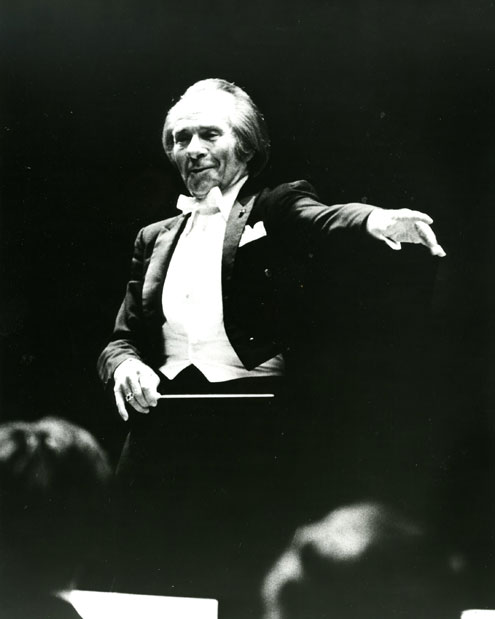

At a recent press interview an excited young lady asked, “What’s it really like up there on the podium making all that music?” The question lit up my flashers: “Deny, deny, deny.” The denial was for her last four words, “. . . making all that music?” The first eleven, though equally difficult to really answer, do elicit a positive – if highly personal – response. But those four final ones – they may have hung a colleague or two, I fear, inasmuch as it has been my lifetime belief that “up on the podium” I don’t make anything; I just try to listen and react. When it comes to making music the program to be played is the only thing that a conductor can do alone, and that is done out of the listening experience that covers one’s conscious lifetime.

Mine probably began at age six when I became aware of my father and his brothers-in-law playing together as fifers and drummers in our family’s fife and drum corps. This was part of the annual day-long celebration of the Fourth of July held at Camp Zeke, which was assembled on the two-and-a-half acres that remained of my grandfather’s pioneer farm in what is now southeast Cleveland. Describing my family’s pursuit of the study of our country’s history through these summer-long assemblies at Camp Zeke is even more difficult than replying to my interviewer’s so well-meant question about conducting. May it suffice to say that 66 years later I have not yet recovered from the wonderful sounds of those shrieking fifes and rattling drums. They really got my attention, and later when Father hung a very big drum around my very little neck and told me to play along, I did what I did by listening to what was happening around me. There was nothing very different about that, but I knew from then that this was to be my number-one way to learn while staying out of trouble.

But just avoiding problems is hardly fit behavior for a would-be conductor; I ran headlong into a full catalog of them. My first group experiences came at Miles Elementary School just across the street from where Camp Zeke ended. At Miles my days of playing mostly without music ended when I was introduced to the Bennett Band Book and the Fox Orchestra Folio. Then a very cute girl pianist in my classroom and I were asked to play a march out in the big main corridor for the changing of classes. In addition to noticing her, I discovered that we sounded louder out in that cold-looking open space than when we practiced on the warm, carpeted stage in the auditorium. Acoustics began to be part of my listening life along with Our Director and Evelyn Bittner, the pianist. Our romance ended a year later when she refused to learn El Capitan, but I’m still chasing acoustics and listening to marches by John Philip Sousa.

Next came my first set of drums as a Christmas present when I was ten. My sister Marjorie and I put together another piano and drums act that we played for parties at the mill where our father worked almost all of his life. Our musical inclinations and nature’s priceless gifts of hearing and retention came from him. When my father was our age there were no musical opportunities such as his interest and support made possible for us to enjoy at home and in school. Home included a 1926 state-of-the-art phonograph and cabinet filled with a variety of records, and that phonograph’s rewarding instant replay set me on my way to begin learning how to listen to music.

The family library included Arthur Conan Doyle’s remarkable Adventures, and it was while reading one of Sherlock Holmes’ recapitulations of how he solved a case by observation and deductive reasoning that I began to apply the Doyle/Holmes words to discipline to become a true listener. The great detective’s companion, Dr. Watson, full of questions when expressing amazement at how Sherlock Holmes had discovered the facts that revealed the criminal, would be chided: “My dear Watson, you see, but you don’t observe.” So too, the musician who hears but somehow forgets to listen, passes rich opportunities to learn.

High school began in the ninth grade when I went to John Adams. There I met a teacher who would further sharpen my listening habits while introducing me to the ordered study of harmonic practice. John B. Elliot’s position on the Adams faculty reflected the unusual commitment of the Cleveland Board of Education to the teaching of music; he was our full-time professional accompanist for everything that happened in school. He also taught a class in theory, counterpoint, form and analysis, and music materials, which functioned in tandem with Amos Wesler’s orchestra and band rehearsals; it was no surprise when both ensembles became national champions. For those who could meet his high standards, Elliot’s classes were a learning experience I could only wish to pass to others; they were to ease me into the next school in my life.

In my high school freshman year Elliot led us through the most detailed and rewarding examination of the Prelude to Die Meistersinger, required music for the Greater Cleveland Contest. I still have that miniature score. From it I began the habit of playing while trying to listen for everything — which in Meistersinger, of course, is everything. Repeated rehearsals afforded me the chance to isolate instruments. As a challenge I would follow each instrument in a single line of counterpoint or play the game of switching concentration from one to another on call. I had heard a lot of music prior to this but now I was really beginning to listen and to think about what I was hearing. Meistersinger became my bible of music composition. Elliot’s classes, Wesler’s rehearsals, and Wagner’s music were exciting lessons for a young man.

There were other lessons for those of us in the Cleveland schools at this time; Music Supervisor Russell V. Morgan had worked out a Saturday morning plan of instruction with members of The Cleveland Orchestra and other musicians in the city whereby we could have top teaching for 50¢ a private lesson given in a centrally located school. Cleveland was truly a hotbed of young musical talent in those years. Families who had recently arrived in the United States had produced first-generation children who were to have everything that might have been denied their parents, including the time to practice the violin every day after school. As I participated, I also learned to listen with them.

Listening to the radio was another of my pastimes. One Sunday afternoon in the summer of 1930, I happened to hear a concert broadcast from Interlochen, Michigan played by the National High School Orchestra. It was a shatteringly wonderful experience and I became determined to get to that camp, however impossible it seemed in the second year of the economic depression. Once again the Cleveland schools helped me, this time when I received a booklet about Interlochen from my mentor, Mr. Morgan. When the camp was short on percussion players for the 1931 session, my talented father found the way to get me there. I date my life from those eight weeks spent between the beautiful lakes in the northwestern Michigan woods.

At Interlochen all my listening and studying and practicing were up for grabs. I found myself in company with a stageful of what had to be some of the most outstanding young musicians of that time. The Interlochen Bowl stage, a magic place for so many of us campers, afforded me the next dimensions in my quest for the education I needed to become a conductor. Here I was listening again, with an added ingredient called competition, that dominant element in the world of professional music making. I’m glad I had to face it at this early age when I was just beginning to learn a few things about myself. Fellow percussionists, older and with two summers of camp experiences ahead of me, were way out in front. Listening as I watched them play, I began to close the gap of experience between us.

I was never without a pair of heavy drum sticks under the belt on my blue corduroys, a rubber practice pad in one hip pocket, and a dog-eared miniature score in the other. (I didn’t need a pitch-pipe for tuning the kettledrums; I just listened to the one nature had put in my head.) The summer was spent listening and sopping up everything I heard at Interlochen.

Placement of percussion instruments (and especially the kettledrums) in large ensembles offers a panoramic view of the technical command of the conductor as well as all that is happening in the other sections. Usually it is while listening from the rear (where balance is easily disturbed) that percussion players lose touch with what is happening in front of them. The percussion part is a problem, for it rarely tells players anything beyond when to play; even how to play and with what is vague. The good percussionist is thereby obliged to become an acutely tuned listener and to develop retentive habits that account for all that is played. Listening while following the score or a violin or clarinet part is much more informative and rewarding than trying to be an adding machine. Listening to the sonorities of which the percussionist’s music is part is the key to balance and the only reliable guide to texture. At camp I had the chance to do this twice daily seven days a week. I had not been there long before my principal concern was to find some way to get back there for my two remaining years of high school.

It was obvious to me from the start that Interlochen is a great separation center. Young men and women there stand at the fork in the road. Camp helps them make the sometimes painful choice: doctor, lawyer, merchant chief – or, for a few, musican. When that field is to be performance, a person had better have a peaceful understanding of the demands. Those who discover that they don’t like to rehearse and who find the daily routine of practicing to be a drag will have to go in another direction. Interlochen groups certainly offer a fair shot at the former. Other factors along with the practicing routine probably help lead a camper to a decision. Mine had been made for me; I simply could not have done anything else in joy or with purpose.

It was interesting to discover that first summer that retentive listening saved me a lot of time and that it wasn’t just the music I could remember. The visual scene of the trees in the grove, the hour of the day with the morning aroma of the canvas awning in front of the bowl being heated by the sun, the look of a Breitkopf & Härtel music cover, the smell of the pines, the way horn players in front of me barely got the tuning slides back in place to play after dumping water – all these are still indelible memories of the first time I played Brahms’s Symphony in C Minor. All these sensory receptions and retentions were stimulated by listening as I heard.

I did make it back to camp the next two summers and was fortunate to add two more disciplines to the experience of performing. The urge to conduct had been fed a bit the first summer when Vladimir Bakalienikoff herded about 50 of us into Grunow Hall for his basic class in baton technique. Knowing that anything beyond that class was strictly daydreaming, I took the only route open to me in 1932 as a potential music leader – the Interlochen course in drum majoring, all 5’1" of me. Mr. Giddings, director of instruction, arranged for me to attend the university class in drum majoring and field tactics offered by Mark H. Hindsley, whose pioneering Cleveland Heights High Marching Band was peerless on the field. His order and logic in teaching those studies were in sharp contrast to the guarded secrets of the twirling baton when I sought some lessons from a counselor at Boys’ Camp. The counselor told me that, in the best tradition of the magician, I could keep what I could steal from him – which I did.

Returning home to my final fall at John Adams I found Mr. Wesler open to the idea that I might be the band’s drum major. At least and at last I could conduct the band for marching although that square one-two, up-down motion didn’t really interest me, even then. My life as a music leader was happening, and I have always cherished the way it began; the long road to a podium was to be shortened considerably by events that occurred in the summer and fall of 1932.

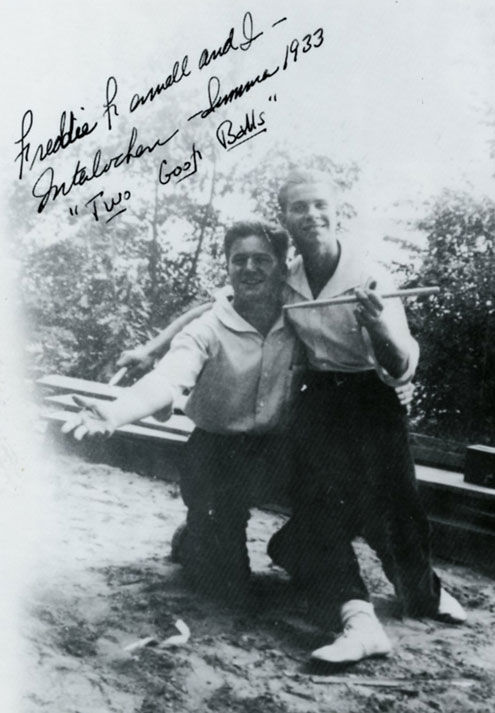

It was time to be thinking about a music school, like the one in Rochester, New York where Howard Hanson was director. We all knew him as annual guest conductor of the National High School Orchestra, and his school had everything I needed, including a generous program of student financial aid. We had talked about it in 1932, but there was no action on my application for admission as late as June of the following year. William F. Ludwig, Jr. became a camper in 1932, and by 1933 we were close friends and sharing the kettledrum stool on a draw lots basis. Bill drew the lot for Hanson’s visit that year. Desperate to make any points with Hanson, I was grateful when Bill offered me his week so that I could play in Hanson’s first Interlochen performance of Symphony No. 2, “Romantic.” This is probably how I became a percussion major at Eastman that September; Interlochen’s fork in the road pointed straight to Rochester, New York.

Bill Ludwig and Frederick Fennell at Interlochen.

The discipline I chose for my final high school camp session was composition. Among the pieces I wrote for class was a mildly successful march. I decided at camp, however, that I would neither clutter nor pollute the world with further creative attempts and that I would devote my life to listening and hopefully to conducting the music of others. This, too, was a listening decision made by all that great music from the National Emblem to The Rite of Spring. Before this abandonment, however, A.A. Harding had invited me to make my debut as a conductor with the National High School Band leading that summer’s march composition at the final concert. A treasured photograph of the occasion reveals all that could possibly be wrong in a very young conductor – except the look on my face.

At Eastman, as at Interlochen, I was free of the usual domestic responsibilities – no trash to take out, no grass to cut, no wood to carry for Grandma Putnam’s magic oven (but no pies and cakes, either). Listening was for keeps at Eastman, where amidst the fast pace I was oh-so-grateful for all to which I had been exposed en route.

If memory is born of interest and listening is fed by curiosity, why not pool all of these as we listen to others perform, practice, rehearse, improvise, warm-up and down, wherever and whenever we find them? I was about to learn some of these big lessons.

The Eastman Years

I had never seen a real chamber music hall, let alone one as strikingly beautiful as Kilbourn, or a theater as impressive as the one that bore the name of George Eastman. Word was that this genius of industry and finance with an obvious passion for music could not (perhaps to his eternal regret) carry a tune in a basket. Maybe this is why he built and endowed so magnificent a school for the training of those who could. Both of these remarkable halls were to become important rooms in my life. Everything about the Eastman Theatre was impressive – the sheer size, the beautiful murals, the elegant crystal chandelier, the big stage – but the setting was not what struck me then.

What made me stop and pay attention was the sound of that marvelous acoustical chamber, which later was to become so vital a part of the many phonograph recordings that the Eastman Wind Ensemble and I would make there.

The first time I heard the special sound of that theatre I was in it all alone – which I never should have been. Over the years the never-should-have-beens were to mount, but for now they were confined to surreptitious forays into the darkened Eastman Theatre, where in the silence of those ghostly surroundings I could listen to the thoughts in my head.

The preliminaries accomplished, I spent those first weeks at school adding to life’s two inevitables, death and taxes, a third called theory – thank you, John Elliot. We music students knew we were in a school of a university where the academics took no secondary place. The parent University of Rochester recently had moved to a beautiful new campus where its College for Men was housed. An aerial photo showed a modest but handsome athletic stadium with high stands on one side. I thought I’d try becoming involved as drum major with whatever football and marching band activities there were. I asked the director of athletics at the River Campus (who also had the challenging responsibility for teaching Eastman’s most hilarious class, hygiene) if he could tell me where I might contact the leader of the band for an audition as drum major. His reply that they didn’t have either lit up all my youthful flashers and this time the printout was: go, go, go! “How would you like to have a marching band?” I asked. “I can organize and lead one for you.” After a silence, which I was fortunate not to break, an unforgettable look of disbelief crossed his face. Two weeks later, however, when several willing sources of energy pooled their resources into a group – many former Interlochen campers joining out of courtesy, other people out of curiosity – Dr. Fauver’s look of approval was unhesitating.

It was a pretty good parade – thank you, Mark Hindsley. My career as a band conductor had begun as an Eastman School freshman with no warning of its arrival and no hint of the consequences ahead. While the money I earned put me through school, the audacity of my act put me in touch with kindred souls, and I had a great need for both. The number one kindred soul and critic (I needed that, too) eventually became my wife after a succession of bone-chilling fall Saturday afternoons and all that attends life with the conductor of a marching band. Dorothy Codner didn’t much care for bands as she heard them, and some of the time neither did I. Doing what we could about that was to consume much of our life together. A violinist who switched to viola, Dorothy was a year ahead of me in school. I was happy to have found myself through her.

School was tough. In addition to old-fashioned competition came grades, class lessons, studio pressure, practice-room checkers, and house mothers. Eastman had been around for 11 years and Howard Hanson had been its director for almost all of them; there was no doubt of his complete (but benevolent) authority and the students’ great admiration for his musical leadership. My little bit of business with Dr. Fauver and the assembling of those never-should-have-been marching Eastmanites (plus men from the college who paid the bills) happened only with his approval.

Eastman’s resources reached beyond practice rooms and marble halls into immediate and intimate association with the thriving professional music life of the city of Rochester, located right across the corridor from the school. The professional life was always part of our education, and non-university groups shared the rehearsal and performance facilities so generously provided by Mr. Eastman. The chance to hear our teachers play for keeps under almost every imaginable ensemble circumstance, six days a week, was the ultimate lesson. Furthermore, when it became apparent that the skills our teachers demanded in the studio were the same ones they needed under the pressure in the professional hall, it encouraged all of us to reach beyond what we had thought was our potential. This lesson, together with the immense holdings in the Sibley Music Library, were Eastman’s greatest assets.

After the initial success of the band that marched while it played, some of the players encouraged me to organize one that sat down in a nice, warm room. The University of Rochester Symphony Band played its first concert on January 25, 1935, on campus. It was my debut conducting a concert band. Howard Hanson was present and requested a repeat performance a few weeks later in Kilbourn Hall. When the dust had settled our name was changed to the Eastman School Symphony Band, and we were added to the ensemble curriculum. I was the group’s conductor for the next 26 years.

Our percussion teacher and performer par excellence, William G. Street, was a solid supporter of my moves toward conducting. At the same time I was still a percussionist, and I practiced the instruments as though that was all I had to do. I performed in all the school’s ensembles, and when I graduated with my class in June 1937, I was Eastman’s first percussion major to receive the Performer’s Certificate.

Bill Street had taken me into the section of the Rochester Philharmonic a few years before. It was an opportunity of priceless value for a young conductor to be part of a group with such a high level of professional playing and to be in the company of international soloists. There was much for which to listen, and I had scores to everything that I could buy of what was played.

The music director of the Philharmonic was the distinguished Spanish musician and pianist, José Iturbi, who enjoyed the privilege of parking his car in the garage under the main rehearsal room. Hearing sounds from above, he came upstairs unobserved to watch a rehearsal that I was conducting with the band. Some days later, to my complete surprise, he asked me to conduct a portion of the same work, Enesco’s Rumanian Rhapsody, so that he might go out into the Eastman Theatre to hear the Philharmonic’s sound and balance. Hearing the wonderful sound of the orchestra coming right at me, so well-played and so responsive to whatever I did, was overwhelming. I began to feel what it was like to be up there on the podium “making all that music.”

My first employment was not as a conductor but as a kettledrummer with the San Diego Symphony Orchestra. I was hired to play the full 1936 summer season at The Bowl in Balboa Park as part of the California-Pacific International Exposition. Others from Eastman, including two players who had gone to San Diego High School with the conductor, Nino Marcelli, were in the orchestra as well. The cross-country trip in my car, mostly alone, was an education in itself. I’d never seen an ocean, and my first view of the Pacific coming up over the brow of a hill in what is now Camp Pendleton was a sight that has never left me. California was very different from New York; San Diego was charming and beautiful. Rehearsing and playing daily in a good orchestra became another way to expand my knowledge of repertory and learn what worked. Playing from scores and listening for everything was endlessly informative.

That summer Otto Klemperer, conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, offered a cycle of the Beethoven symphonies on Monday nights at the Hollywood Bowl. We San Diego players had the night off, so in company with Norman Herzberg, our first bassoonist and Harold Kurtz, the flutist who had steered us into the San Diego job, I drove to Hollywood to hear performances of those masterworks. Seated on the fringe of the sound in the Bowl I heard things that I still associate with the proper interpretation of this literature. The lack of amplification did not seem to hinder the strength of the music. Klemperer was impressive, not only as a conductor, but also as one so tall that he did not need to use a podium.

One Monday afternoon the San Diego’s wind players and I went neither to the bathing cove at La Jolla nor to Klemperer’s Beethoven. Instead, John Barrows, our principal hornist, assembled us at his family home, a classic California wooden cottage with ample room and a great sound for chamber music. Among the works to be read was a piece I had not heard, the Serenade, Op. 7, by Richard Strauss. I was along as a listener, but when things became a little rocky in the middle section (B minor, piú animato) Herzberg suggested that I assist the ensemble. The subsequent play-through was the beginning of a long love affair with this charming piece; I had found one of the pivotal scores that would lead me to the Eastman Wind Ensemble. At summer’s end Norman and I went to see the Big Trees at Yosemite; at last they were more than just black-and-white photos in a geography book.

School and the marching band season began without Dorothy, who had graduated and returned home to Iowa. In 1935 the University of Rochester had a new young president, and somewhere among the myriad questions asked him was one by a local sports writer as to when the band might get some real uniforms. His casual reply that an amount would be allotted for the fall of 1937 was enough encouragement for me to request a cost quote from Greenville, Illinois. The quote led to drawings and a fitting session for all the men who would return. With the slim assurance of a few devoted alumni that somehow the bill would be paid, I gulped a few times and sent in the order. Two weeks later I hurried off to Iowa to be married.

The automobile trip to San Diego and the 1937 summer season of the San Diego Symphony were our honeymoon. Back in Rochester, the new uniforms had arrived, along with a huge bill. I went to see President Valentine, the bill in my hand and my job on the line. Somehow, and with his appreciation of what the band had been contributing, another never-should-have-been came to pass.

Both Dorothy and I were in graduate school on a very tight budget – hers! We practically lived in Sibley Library, researching our material for dissertations in music theory. The Orchestral Development of the Kettledrum from Purcell through Beethoven demanded and got every other minute of my time for two years; the rest of my work went on around it. I became a looker as well as a listener. Research to support the thesis meant that I had to explore all printed scores before Purcell and then patiently to peruse every score in the complete works of Purcell, Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. Through this survey of a composer’s use of the kettledrums I had the chance to observe much beyond that area as well.

School had barely begun that fall of 1937 when a notice appeared on the bulletin board from the Institute for International Education Lifetime Listener advising that applications for the Salzburg International Prize in Conducting should be completed by the first of October. The Mozarteum in Austria would award the prize the following summer. This was the only prize for a young conductor at the time, but confidence that my training and experience made me eligible was tempered by a realization that conductors of bands sat rather low on the artistic totem pole. I vividly remember dropping that application in the Eastman corridor mailbox and thinking, “Well, who knows?” Howard Hanson, José Iturbi, and Vladimir Bakaleinikoff had agreed to let me list them as sponsors; when time passed with no acknowledgement, I finally ceased to think about it. The mountain of paper on my Sibley study cubicle received all of my attention. On the 28th of February word came that I had been awarded the prize after a jury had secretly visited the darkened Eastman Theatre during a Symphony Band rehearsal.

Dorothy’s and my happiness at this great opportunity ended as abruptly as it had begun with the news on March 12th that Hitler had completed the annexation of Austria for the Third Reich. Wanting no gifts from Nazism, I relinquished the prize, and my disappointment was eased when the Mozarteum Academy’s summer plans were cancelled. Dorothy and I were in Iowa for the summer when I received a telegram from Howard Hanson stating that the prize was on again. The State Department requested that I please be in Salzburg by July 10th. Somehow I was, and alone. The sudden change from pastoral Iowa to the busy decks of the German liner Europa found me with my nose once again in a German dictionary.

The first night in Salzburg I lodged in a comfortable private home. The score to Mozart’s “Jupiter” rested atop a great white down comforter as I read my way into the spirit of my new surroundings. Amid reflections of the family, teachers, and players who had sent me there, sleep was about to claim me when I heard the distant but unmistakable sound of marching boots approaching in a precise crescendo. Then this rude interruption of Mozart and my reverie became the accompaniment to German soldier songs. As the marchers sang and passed, sleep no longer came easily or peacefully. I knew that evening in Mozart’s beautiful hometown, as a wonderful time was beginning for me, that things were about to go all wrong for lots of other people; those boots in the night were just an omen of its beginning.