As percussion students develop their drumset skills, they tackle many challenges at once: playing very different instruments as a unified group, coordinating up to four limbs at one time, and reading multiple lines of notation when provided. They must learn to balance dynamics across the instruments in their set while also matching their overall sound to the ensemble. They may be asked to create an appropriate drum fill on the spot, change their pattern to accommodate other performers, and carry the weight of the ensemble’s tempo squarely on their shoulders. These basic skills make drumset playing challenging at first, but with time and effort, young musicians can learn them all.

Nuance

What remains is the development of nuance, which takes players’ imaginations beyond what they are playing to how they are playing it. Nuanced playing requires a personal approach and depends on the particular musical circumstances. Students can explore several aspects of advanced drumset techniques when developing their personal styles.

Each instrument of the drumset offers countless options for timbral variation. As students play steady eighth notes on the hi-hat:

• Do they play them all at the same dynamic or with slight ebb and flow to match the groove of the piece?

• Are they playing every note with the tip of the stick or do they use the shoulder occasionally or systematically for an accent or accent pattern?

• Do they play way out on the edge? In the middle? On the bell? Some combination of all three?

• Are the two cymbals tightly closed with the foot or quite loose? Somewhere in between? Does that change?

As players try these options, they will learn that there are many possible answers. Of course, similar questions apply to other instruments, too; the snare drum and ride cymbal, for example, offer many parallel options for experimentation.

Players can also explore nuance more specifically through dynamics. The snare drum notes in a rock or funk pattern and the cymbal notes in a swing ride pattern, for example, are rarely played at equal volume. Students should try varying the dynamics in these typically repetitive parts, specifically by exploring the extremes of dynamic contrasts. They should see how soft they can make the snare drum ghost notes in relation to the accented backbeats. Even straightforward patterns become highly engaging when players find the right dynamics.

When balancing dynamics, students should focus on the bass drum, an instrument often played too loudly compared to the rest of the kit. One cause of this problem is that inexperienced players are still getting used to the natural resistance of the spring in the pedal, the feeling of the weight of their leg, and the rebound provided by the head. They should experiment with playing the softest notes they can, mostly by keeping the mallet of the pedal close to the head, so they develop the control to pick and choose the dynamic nuance they need when the time is right.

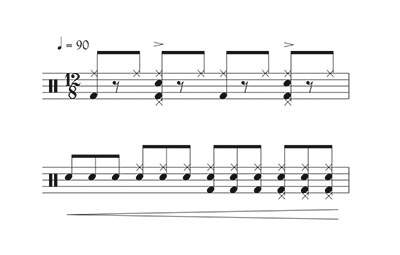

Players can also explore nuance through texture, determining what combinations of limbs on various instruments provide the best support for the ensemble at a given moment. They might start a rock or pop ballad with just the hi-hat and bass drum before layering in the snare drum to create a sense of organic growth that mirrors the lyrics. They could begin the head of a jazz chart with just the ride cymbal and high-hat foot, followed by gradual or sudden inclusion of bass and snare to comp a soloist on the repeat. They could gradually build the texture of a steady triplet fill on a shuffle tune by adding one limb at a time for each beat, as shown below.

Students learn by hearing many examples of how professionals approach these musical circumstances, and teachers should remind them that notated charts can be misleading. For example, the shuffle fill as performed in the example above might originally have been sketched on the player’s part simply as constant triplets on the snare drum, while something much more dramatic and engaging is necessary.

Setting Up the Band

Interpreting notated drumset parts is essential for successful performances. Setting up the band is one of the most misunderstood applications of this skill. Typical examples arise in jazz big band charts, when the drummer kicks the band into a loud, rhythmically unified phrase. Particularly when the band enters on an upbeat, the drummer should provide a strong downbeat at the point of departure, offering a clear reference point for the timing of the group’s entrance. For example, given the ensemble statement shown below, the drummer might play a short fill leading to a heavily accented note on beat 3, to prompt the group to enter cleanly and confidently on the offbeat.

.jpg)

Jazz arrangers will often write small cue notes above a drummer’s part to indicate what the horns are playing in such a phrase. Remind drummers that the goal is not to play those notes, but to set up those notes for the ensemble

Setting up the band is certainly not limited to one style; drummers should always consider how they can help their bandmates to play their best. For example, they need to decide how busy a pattern should be to interest listeners without interfering with the soloist. They should consider how early to start a fill after the introduction to reduce musical downtime and maintain ensemble balance. When a chart alternates between musical styles, they can foreshadow the transitions with rhythmic manipulation and varying timbres. Appropriate use of the tom-toms, for instance, can provide color and signal musical change. Teachers can raise these issues for players without providing the answers, giving them the skills to address future scenarios themselves.

Brushes

Playing with brushes is a common but misunderstood technique. Brushes are not just softer versions of drumsticks. They are different musical tools altogether, and present opportunities to maintain diffuse contact with the surface, create physical friction, and expand timbral variety. I recommend using retractable brushes to be able to adjust the spread of the wires and protect the wires within the sheath when not being used. The brushes can be opened just slightly to create a more compact striking point when desired, or fanned more broadly for general playing involving swishing on drumheads and other surfaces.

Many inexperienced players interpret Play with brushes on jazz charts to mean they should play just as they would with sticks, but using the brushes to reduce the volume. This is rarely what the composer or arranger intended. Instead, a player could maintain constant oval-shaped swishes between 5 o’clock and 11 o’clock on the snare head with one hand, outlining quarter notes either with each oval (slower tempos) or with each half oval (faster tempos). The other hand softly taps or lightly swishes the typical swing ride cymbal pattern on the same snare head.

Playing with brushes this way maximizes contact with the head, a priority for this technique in most musical situations. Generally, brushes should be used much more frequently for constant contact and lateral motion on the surface they are playing than for tapping it. Players can practice the same patterns and fills they normally play by tapping with sticks, swishing these rhythms between the hands with constant contact on the head. Simple back-and-forth motions and small circles work best, especially with less experienced players.

Understanding Their Role

All of these recommendations guide players to develop a sophisticated concept of their musical role. Due to the versatility of the instrument across musical ensembles and styles and the typically vague or even nonexistent printed parts, drumset players should learn to welcome musical surprises, trust their ears and instincts, and, above all, be prepared to support the group by discovering needs and creatively filling them. The best way to develop these skills is to play with many different musical groups. Teachers can help by matching percussion students to drumset parts early in their studies and rotating those parts frequently among players. The longer that one student remains the best drumset player, the harder it is to break that mold and give everyone the opportunity to learn.