Cadenzas are the virtuosic and improvisatory sections performed by soloists, traditionally located near the final cadence, in concertos. Cadenzas have changed considerably in nature from the baroque period to the present day. Although from the romantic period on, the composer tended to write out the cadenza as part of a published concerto, performers often improvised them in the baroque and the classical periods. I have come up with a relatively simple method for creating convincing cadenzas. In addition to my background in music theory, I studied 34 cadenzas from different periods to help me derive this method.

About Cadenzas

To create cadenzas, it is first necessary to understand how are they are typically structured. They usually have one or more large parts, each of which can be divided into smaller sections. The shortest cadenzas tend to have one or two subsections, short cadenzas have as many as four subsections, and long cadenzas will have anywhere from four to eleven subsections. Virtually every cadenza ends with a trill on the supertonic or occasionally the leading tone.

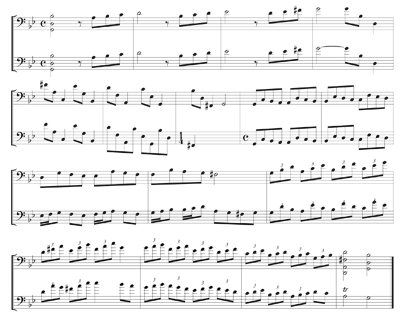

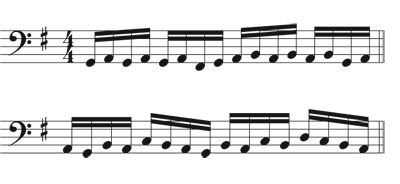

Each section is typically comprised of a mixture of arpeggios, scales, chord progressions, and quotations of melodies from the concerto. Often these sections are ornamented in some way. These short cadenzas show some of the many variations possible and include variations and ornamentations on scales, scale fragments, and arpeggios.

Constructing a Cadenza

Play, analyze, evaluate, and listen to as many different cadenzas as possible. An analysis should determine as much about the structure of each cadenza as possible, including form, keys, chord progressions, and compositional devices used. Analysis makes it possible to alter a cadenza by changing notes or by adding new sections that fit with what is already there. The aim of rewriting and adding material is to use every device you can think of to delay resolution of the ending trill as long as possible. This can help get you caught up in the tension and energy of the cadence itself.

Toolbox of Devices

To come up with cadenzas that are good, interesting, and believable, a wide variety of devices will be needed. Possibilities include chromatic and diatonic scales, arpeggios, broken arpeggios, filled-in thirds, neighbor notes, appoggiaturas, anticipations, escape tones, and turns. For practice, group variations of these by type and practice them in all major and minor keys, working the tempo up until they can be played cleanly at prestissimo. The fast tempos are particularly important if you want to make each of these figures sound automatic.

One way to make a passage sound sophisticated is to combine these figures into larger, compound motives, as shown below.

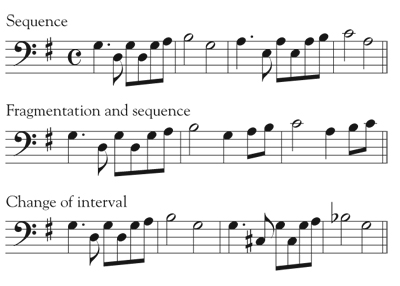

Sequencing, the process of taking a figure and transposing it to different pitch levels in a stepwise fashion, plays a large role in Western music, and a cadenza will sound more mature and authentic with use of this device. A figuration should be sequenced for at most four repetitions, with two or three being more preferable than four; after this, the pattern becomes too predictable. Along these lines, another important concept throughout much of the history of Western music is bar form, which refers to an AAB (statement-repetition-contrast) pattern on any scale, large or small. The first time something is repeated, it is corroborated and reinforced, but repeating something a third time is predictable and redundant. Therefore, as a default, consider playing a figure at two or three different pitch levels before varying it.

Use occasional fermatas to separate sections and to give a feeling of recitative or improvisation. If a cadenza lacks these occasional breaks, there is a danger that everything will run together and sound like random, frantic chaos.

Chord Progressions

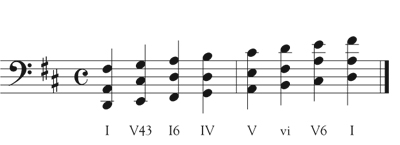

A good chord progression can be the most effective dramatic and powerful device in a cadenza. A chord progression can be easily and smoothly inserted after any fermata. Most chord progressions are built over a stepwise diatonic or chromatic bass line, which usually ascends to the fifth of the key, but sometimes modulates to a new key. Other options for chord progressions include playing the chords over a pedal fifth or moving around the circle of fifths or fourths.

It is rare that chord progressions are played as a series of block chords, even on instruments capable of producing three or four notes at a time. Usually, it is preferable to arpeggiate chords in some pattern. Several common patterns are shown at the bottom of the previous column. Many other possibilities exist; to create new patterns, try changing the order in which the chord notes are played or using different articulations.

A useful, albeit simplified, method for determining good stepwise chord progressions is known as the rule of the octave.

The example shown is in a major key, but the rule is essentially the same in minor keys. Knowledge of this rule makes it easier to improvise believable chord progressions. It is unnecessary to play an entire scale in this manner, the aim is to move around within a scale while harmonizing each note of the scale with an appropriate chord. Other chords that tend to work well with stepwise bass lines, chromatic or otherwise, are shown below.

Fully diminished seventh chords are perhaps the most important and idiomatic chord in cadenzas, because they can be inserted almost anywhere and followed with almost any device in multiple keys. If there is difficulty writing a transition in a cadenza, use a fully diminished seventh chord. Getting a feel for chord progressions may take some time; be patient and persistent.

Tune Quotes

Tune quotes are the three or four primary melodic themes in the movement. Quote part or all of one of these tunes after a fermata, or simply at an implied cadence at the end of any section in your cadenza. It is good to play the melody in a key in which it has not previously been heard. Mediant key relationships usually work well. The following simple examples are based on a tune called “I’ve Been Working on Cadenzas.”

Advanced Devices

Once a basic framework for the components of a cadenza is set, there are numerous options to make it sound more sophisticated and interesting. With scales or arpeggio passages, try applying one or more ornamentation patterns or a distinctive rhythm or articulation. Changing registers can sometimes be beneficial too.

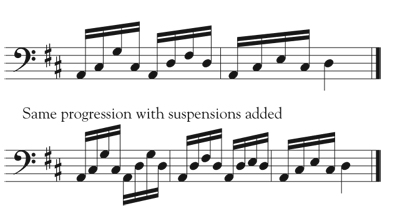

Add suspensions or neighbor notes to chord progressions. When there is stepwise voice-leading motion between chords, suspension figures can be created by changing notes from the old chord to the new chord one at a time. For example, if a chord change requires moving two notes, move one note first and then move the other a bar later.

There are also many possibilities for altering tune quote passages. Try adding some additional trills. Experiment with changing the key or mode. You might also consider pausing on occasion to add scales or arpeggios; cadences are usually the best place for this. String, percussion, and keyboard players can also add double stops.

Finally and most importantly, consider developing the tune in some way by fragmenting it (reducing it in length or removing a portion of it), sequencing (repetition at different pitch levels), and interval alteration (i.e., changing a leap of a third to a second, etc.). Adding some development like this can make a cadenza sound sophisticated and almost always helps it sound more improvisatory.

Getting Started Writing

A simple cadenza might have four sections. The first and third sections can consist of scales or arpeggios, while the second section could have fast or slow chord progressions, tune quotes, or additional ornamented scales and arpeggios. The final portion of a cadenza should be a trill on the second or seventh.

One option for someone who has no idea how to begin writing a cadenza is to create a random cadenza generator by using the musical examples in this article and a pair of dice. Roll a die to determine how many sections your cadenza will have and then roll for each section to determine its primary content (scales, arpeggios, chord progression, or tune quote). If a section consists of scales or arpeggios, roll to determine whether to ornament them. For the ones that are to be ornamented, roll the dice to see which type of ornamentation to use. In some cases, the dice may say one thing but another idea seems better; choose what seems to work best. This is not the ideal way to create a cadenza, but sometimes seeing random possibilities can help to alleviate the fear of making that first attempt, and the end result might sound better than expected.

With practice, the ability to write an interesting cadenza will improve. Once you understand the basics of writing a cadenza, the knowledge can be passed to students; having them write cadenzas is a great way to motivate them to learn scales, arpeggios, and double stops. Writing cadenzas will also provide increased enjoyment in the music you play.

* * *

A Sample Cadenza

The example below shows two versions of a cadenza. The top line is what a student of mine wrote, and the bottom line includes changes that I suggested that she consider making to make it sound more interesting. In measure four, I suggested adding a tie. Ties and rests are excellent tools; changing too often on the beat can sound unsophisticated and predictable.

The changes in measures six, ten, and the first half of eleven add rhythmic interest and avoid monotony. The change that I suggest in measure seven is made to avoid an early cadence on G, the tonic note. Too many cadences on a tonic chord give a cadenza a fragmented sound. The second half of measure eleven is altered to avoid sitting on a sustained seventh, which should rarely be sustained explicitly for long.

Measure twelve has been altered to create a more interesting and less simplistic arpeggiation pattern. The first half of measure thirteen is altered to avoid predictability, and the second half is altered to avoid a premature cadence on the tonic note. Measure fourteen has been altered to create a compound motive instead of a simple one. After making this change, the audience will have only heard the pattern twice after one measure, as opposed to four times. The change at the end of measure fifteen was suggested to set up the cadence and to prevent it from seeming predictable.