We asked some of the master teachers and performers presenting at the Midwest Clinic to share one tip from their upcoming clinics. Here is a taste of what to expect during the conference.

.jpg)

Survival of the Fittest: The Small School Band Director

Donny Longest

Wednesday, Deccember 20, 10:30 a.m.

Having spent 29 of my 33 years teaching in a small school, I realize what a daunting task it can be. In a small town in the middle of nowhere America, with no other music person on the teaching staff or maybe not even in the town, you have the opportunity and responsibility to educate the students about music. However, my years in the small schools were the most rewarding I could ever have. I firmly believe that you will influence the students that go through your bandroom. It is up to you to develop the professional relationships with students, staff, and the community that determine if that effect is positive. That positive influence encourages students to work harder in rehearsals, while helping you garner support from the school staff and community that pushes the program forward.

Donny Longest recently retired after 33 years of teaching in Oklahoma. He is the Executive Secretary for the Oklahoma Bandmasters Association.

Teaching Improvisation through Etude Writing

Bob Habersat, Paul Levy

Wednesday, December 20, 10:30 a.m.

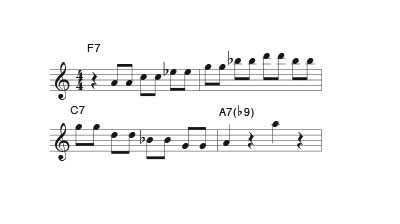

Jazz improvisation is often taught in a large group setting with the only instruction being, “play this scale on that chord.” This method doesn’t set students up to succeed, and they often become frustrated or intimidated when it is time to solo. Having students compose their solos ahead of time removes the unnerving element of improvising.

The two-step etude writing tool on shedthemusic.com allows young players to make a great sounding solo quickly and easily. There is a library of blues licks that have been transcribed from notable jazz musicians and organized into first four, second four, and last four measure phrases. These licks can be mixed and matched together by simply copying and pasting them from our free interactive Noteflight scores into to a blank document.

Here is a sample etude that has been created using three licks that have been taken from different artists.

Wes Montgomery, Au Privave (Cannonball Adderley and the Poll-Winners)

Joe Pass, Relaxin’ at Camarillo (Joy Spring)

Wynton Kelly, Dis Dis (Hank Mobley: Soul Station)

When your students have written a solo, have them practice the notes and rhythms until it sounds like their own. A steady diet of writing solos and listening to jazz will create improvisers who will want to take solos.

Paul Levy is the band director at Oak Lawn (Illinois) Community High School.

Bob Habersat teaches Honors Music Theory 1, Honors Applied Music Theory, Guitar 1, Guitar 2, Guitar Studio, and Music Technology at Oak Lawn Community High School.

Antidotes for Performance Anxiety: Teaching Confidence

Miranda George

Wednesday, December 20, 10:30 a.m.

To learn how to move through performance anxiety one must understand its origins. I theorize that there are three main causes for musicians’ performance anxiety:

• Adrenaline: shaking caused by excitement or benign pressure.

• Instability: a removal from habit caused by unforeseen events, setting off the fight-or-flight response.

• Shame: the fear of disconnection, a deep sense that one is not “good enough”, setting off the fight-or-flight response.1

Shame-based performance anxiety is the least discussed of these three. According to renowned shame researcher Brené Brown, shame is the deeply held belief that one is not good enough – the idea that one is unworthy of love and belonging. “Shame lives and thrives in secrecy, silence, and judgment”. Musicians who are not resilient will either over-function or under-function in response to shame.1 Examples of over/under-functioning in response to shame include: negative self-talk or self-imagery, unfair expectations, self-sacrifice or lack of self-care, over-practice, obsession, mistrust, faithlessness, evidence seeking, constant surveillance, scarcity mindset, hustling, comparison, perfectionism, fear of disapproval, social inauthenticity, alienation, procrastination, and apathy.

For many musicians who experience performance anxiety, their first instinct is to attempt to run away from it. Responding to performance anxiety with panic will only make things worse; performing with worthiness requires authenticity and a realignment of motivation. Breathing in and out slowly and practicing self-compassion helps dissipate uncomfortable symptoms by taking a moment to be mindful, treating oneself like a dear friend would be treated in the same situation. I offer the following prompt, inspired by self-compassion researcher Kristin Neff.2

Write down or say out loud: “I am struggling with [name symptoms, i.e. tense, shaky, short of breath, unable to focus, etc.] That is because I feel [name emotion, i.e. excited, scared, uncomfortable, doubtful, etc.]. It is okay that I feel this way. I’m not alone. I’m not the only one who experiences this. This feeling is temporary. [Be sure not to over-identify with emotions or symptoms.] I am doing the best I can with what I have.”

Start a conversation about performance anxiety with your fellow musicians and/or students. “Do you ever feel nervous or tense when you perform? How do you feel when that happens? What do you do to get past it?” Teachers and students will find that the greatest antidote of all is hearing someone else say, “I’m with you.”

Miranda George has been a freelance trumpet player and teacher in the Dallas/ Fort Worth area for more than 15 years.

Sources

1The Power of Vulnerability: Teachings on Authenticity, Connection, & Courage. by Brené Brown, 2012.

2Self-Compassion by Kristin Neff, 2011.

Listen with Your Eyes

Josh Byrd

Wednesday, December 20, 12:00 p.m.

Why do students make bad sounds? Most often it is not an intellectual or musical roadblock that gets in the way. It is a physical concept that needs to be addressed. Consider the following problems and teaching suggestions:

Airy clarinet tone: “Focus the sound.”

Abrasive cello tone: “Gentle, like a mountain goat’s feet on the walls of Machu Picchu.”

Sharp trumpet pitch: “Listen.”

Violent, angry triangle sounds: “Not so much. It should sound like ting.”

Such suggestions are not only common, they are frequently the default statements for younger teachers. Instead of just listening with your ears, listen with your eyes to find what might be causing these types of sounds. For the clarinet problem above, have the students show you their setup. Are their reeds too far down, or is one of them chipped so badly it resembles a mountain range? As for the cellist, where are they playing in relation to the bridge? Did the student forget to tighten the bow prior to rehearsal? Are any of the trumpets’ main tuning slides pushed all of the way in, or is the pitch problem one person out of fifteen playing a Bn instead of a Bb? How is your percussionist holding the triangle? The beater? How is his arm moving?

These types of problems require not only listening and watching, but focused observation. Moving around the ensemble allows you to see and hear what each student is doing, while also holding everyone more accountable. Know that many horns are going to get away with bad hand position if you only shout its importance from the conductor’s stand. Getting up close and personal can be very informative. For instance, it is nearly impossible to identify a clarinet beginner articulating with bursts of air instead of the tongue without watching and listening to students individually.

It can be frustrating to know that something needs to be changed but not know what that something is. It is often easier to identify what is wrong than to fix the problem and its accompanying concepts. Young teachers so often default to a verbal explanation as to what should change with the sound, but not with the instrument or its approach. Much like when you’ve been pulled over for speeding, talking your way out of it rarely works. There are concepts that surround the craft of playing each instrument in your ensemble. Physical suggestions are not only more pertinent; they can also have a longer lasting effect.

Josh Byrd is Director of Bands and Associate Professor of Music at the University of West Georgia.

Composing with My Middle School Band During Rehearsal

Travis J. Weller

Wednesday, December 20, 1:45 p.m.

Colleagues often ask what they can do to help their students who have an interest in composing. I would simply say that although you might not consider yourself a composer, you spend the bulk of your day as an educator, you are a musician as well, and you are training musicians. Not every musician can be a composer, but a composer can come from anywhere. The ability to perform on one’s instrument and spontaneously compose – essentially improvisation – matters and can provide a unique outlet for germinal ideas to form.

Once a student develops an idea that he finds unique and appealing, I would encourage him to record it. I frequently use the voice memo feature on my phone to record ideas, and most students would be at ease doing the same. This audio sketchbook can be revisited later for purposes of transcription, or further development. Transcription teaches students a number of basic skills in theory. The reflection upon revisiting the germinal idea might generate further extensions or even suggest contrasting material that offers their composition an appropriate amount of balance.

Travis J. Weller is the Director of Music Education and The Symphonic Winds at Messiah College.

Developing Beautiful Tone and Articulation

Winifred Crock, Laurie Scott

Wednesday, Dec 20, 2:30 p.m.

Helping students produce a beautiful string tone is one of the most important and most fundamental teaching processes. When string students create clear, strong, and beautiful sounds from the first and continue to further build technique, they develop a unique palette of expressive tone colors, articulations, and dynamics. Analysis of weight, speed, contact point, bow tilt, and touch point furthers an understanding of the interrelationship of these factors in sound production. Defining and analyzing sounds with ideas such as strength, clarity, and continuity fosters growth in individual players as well as a unified ensemble sound. The concept that notes have a beginning, middle, and an end is a great way to start.

Winifred Crock spent 25 years as the Director of Orchestras at Parkway Central High School in Chesterfield, Missouri and has a private violin studio in suburban St. Louis, Missouri.

Laurie Scott is Associate Professor of Music and Human Learning at The University of Texas at Austin.

Percussion – Magical, Musical, Marches

Kevin Lepper

Wednesday, December 20, 2:30 p.m.

In most performances of marches the percussion sounds are approached with the all-parts-are-equal concept. Besides choosing the right instruments – decisions that include snare size and tuning, cymbal size and sound, bass drum tuning and mallet choice, bell range and mallet choice, and timpani drum selection and mallet choice – you can identify what percussion instrument defines each section. These changes will provide new colors and life to a familiar form. For example, when performing Amparito Roca by Jaime Texidor, keep in mind the instruments of a bullfight ensemble (snare drum, crash cymbals, bass drum) as well as typical Spanish instruments (castanets). Here is a possible percussion section definition solution:

Introduction: – full ensemble

Phrase 1: snare drum leads

Phrase 2 : bass drum leads

Phrase 3: snare drum 16ths with cymbal crashes

Lyrical theme : castanets

Ending Phrases: isolated hits from crash cymbals and bass drum

Band directors often massage the wind parts to get the sound color that they desire, now it’s time to go the next level and do the same thing for the percussion section.

Kevin Lepper is Professor Emeritus at VanderCook College of Music and a freelance percussionist and educator in the Chicago area.

Complete Pedagogical Concepts for Low Brass Performance

Daniel Perantoni

Wednesday, December 20, 2:30 p.m.

Our breath is not used to fill the instrument but is used by the embouchure as energy to make the lips vibrate. The tuba is an amplifier and reacts according to its acoustical properties.

Successful performance demands the development of good physical habits that will happen naturally, like the simple task of picking up a pencil. Be concerned with the doer; one can only play as well as he or she hears. Listen to master performers on all instruments. Imitation is still the best teacher. It is helpful to develop your ear through singing. This will strengthen a closer awareness of pitch, melodic line and expression. Sing everything in your mind while playing the tuba. Finally, put it all together (air flow, embouchure, tonguing, etc.) into one concentration, which is the making of music.

Points of discussion for successful performance are posture, inhalation, exhalation, articulation, intonation, range, vibrato, common sound problems, and making music.

Daniel Perantoni is Tuba-Provost Professor at Indiana University’s Jacobs School of Music.

Rhythm Reading Routines

Rhonda Rhodes

Wednesday, December 20, 4:00 p.m.

Large rhythm flashcards can be used in myriad ways in the instrumental classroom. For example, try a classroom version of “Heads Up Charades” by holding a stack of rhythm cards slightly above your head, the rhythms facing out toward the ensemble. Make sure students know you haven’t peeked at the rhythms on the cards. Ask the group to play the rhythm on your count-off. The aim is for them to play the rhythm clearly enough that you can describe it back to them after one hearing.

For the times when the group does not play it clearly, you have a few choices: simply ask them to play it again, or (a better response) give them an answer along the lines of “It’s either _____ or _____. I couldn’t really tell how long you intended the last note to be. Play it again for me.” Go through a series of three or four cards as part of your warmup.

Rhonda Rhodes teaches courses in music education, woodwind study, music theory, and ear training; woodwind ensembles; and private saxophone lessons at Dixie State University in St. George, Utah.

S.M.A.L.L. Band Programs: Strategies for Success

Brandon E. Robinson, David Robinson

Thursday, December 21, 8:30 a.m.

Some challenges facing small bands include: sound, music, arranging, language, and leadership. There are a variety of approaches to assist band directors in these five specific areas. Custom music arrangements can highlight students with advanced ability and accommodate deficiencies due to a lack of experience, skill, or instrumentation. When hiring an arranger for your band or arranging for them yourself, here are some key points to consider:

• Know how you want your ensemble balanced.

• Do not write more than two parts for clarinets, alto saxophones, trumpets, mellophones, or trombones.

• Instead of splitting into three parts, fill out the chords in other voices.

• Alto saxophones and mellophones can be used to reinforce woodwind or low brass parts.

• Range and endurance should be a priority when arranging for your ensemble.

Brandon Robinsonis Associate Director of Bands at Wake Forest University.

David Robinson is Director of Bands and Assistant Professor of Music at McMurry University in Abilene, Texas.

Maximizing Gestural Expression

Dustin Barr, Jerald Schwiebert

Thursday, December 21, 11:30 a.m.

Why do the world’s great conductors seemingly move so differently? Each appears to have a style and manner of movement that is uniquely theirs and that sometimes seems only tangentially related to the practices and recommendations laid out in most traditional conducting textbooks. To fully understand this, it is perhaps a more manageable task to look at how the world’s great conductors move similarly.

The simple answer is that they move with a sense of sincerity and authenticity. Their bodies flow with a coordinated grace that resonates throughout their whole being. It includes movement – often subtle, sometimes considerable – in their torso, shoulders, neck, pelvis, legs, and throughout their entire body. No excess energy is wasted on holding parts of their body still. Their entire body may not always move much, but they always retain a sense of fluidity that allows for unencumbered movement when necessary.

The kinesthetic authenticity demonstrated by leading conductors, however, is a direct result of their mental energy. Communicating their musical intent is not a byproduct of their conducting technique – their conducting technique is the vehicle by which they communicate their intent. While this sounds like a mere variation in semantics, the difference can be profound. Placing emphasis on the act of communicating expands the focus of the conductor and allows the body to resonate naturally. Emphasizing technique above all else encourages the mind to retreat inward, focusing on the self, and consequently, inhibiting movement in parts of the body.

Jerald Schwiebert is one of the country’s foremost authorities on the study and application of the capacity for human physical expression and spent 20 years on the faculty of the School of Music, Theater and Dance at the University of Michigan.

Dustin Barr is Director of Wind Studies and Assistant Professor of Music at California State University, Fullerton.

Herding the Cats: Reflecting Your Priorities as You Teach Jazz Improvisation

Antonio García

Thursday, December 21, 11:30 a.m.

Many factors can challenge how you grade an improvisation course – or even how you allocate time and energy within it. There is so much to learn from digesting the different, effective means by which any number of successful jazz educators address the art of teaching – and grading – jazz improvisation courses. By focusing on the potential dichotomy and intersection between the teachable and unteachable elements of improvisation, plus the concrete and the abstract, as well as the technical and the creative, we will be better equipped to address and reconcile these factors in our teaching and grading.

As just one example, dual competency levels can be extremely effective in a class with a wide range of student improv experience. It is fair when articulated in the syllabus, is easy to track, and takes the pressure off both you and students to otherwise have the less-experienced students in the room achieve the same outcomes as the ones who walked in able to solo well. I am grateful to the late Donald Funes, then Chairman of Music at Northern Illinois University, for showing me how to accomplish that at the beginning of my teaching career so that my assigned grades would indeed be defendable in light of any later grade challenges by students who might perceive a double standard in the class. However, within surveys I conducted, only 11% of the respondents teaching improv courses used dual competency levels as a means to grade their students fairly.

Trombonist, vocalist, composer, and educator Antonio García is director of jazz studies at Virginia Commonwealth University and an executive board member of The Midwest Clinic.

Mindset for Music

Thomas Hooten

Thursday, December 21, 3:00 p.m.

In my clinic, I will discuss the psychological, practical, and emotional aspects of being a performer. I believe that in our development as instrumentalists, we need to have coordination between the mind and the body. For example, one simple exercise would be to learn how to time your breath with the music that you are about to play. Practicing this in a warmup while working on fundamentals is a great place to start. I will discuss other tips on how to create this coordination, along with practical advice regarding audition and performance preparation.

Thomas Hooten is Principal Trumpet of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra.

How to Teach Alternate Fingerings for Woodwinds In Your Ensemble

Nicholas Thomas, Emmanuel Rodriguez

Thursday, December 21, 3:30 p.m.

We will discuss brief techniques and pedagogy that will show novice teachers quick teaching points to improve their woodwind sections. Emphasis will be on common alternate fingerings to facilitate dexterity of playing and common pitch problems. Also, discussed will be woodwind sliding concerns, common key sounds, and bumping.

Nicholas Thomas is Coordinator for Music Teacher Education and Assistant Director of University Bands at Florida A&M University.

Emmanuel Rodriguez is Director of Bands at Miramar (Florida) High School.

Changing the Culture from the Inside Out

Stan Mauldin

Thursday, December 21, 4:30 p.m.

Shortly after I was named the new Director of Bands at Seguin ISD, the Seguin Band was contacted by a tour company: “Another band has had a change of directors and decided give up its performing time in Carnegie Hall. Would the Seguin Band have an interest in taking the spot?” The impossible task at hand was to raise approximately $260,000 and perfect a Carnegie Hall Concert Performance that included Rhapsody in Blue in 90 days. How did the Seguin Band do the impossible?

The goal must be large enough to engender community support and, therefore, allow the band to raise large sums of money. KWED, the Seguin radio station, sponsored seven days of giving where the community came together to support the band’s trip to New York. In a week the band raised over $28,000 from individual small donations. We formed small ensembles and performed at every Christmas party, Rotary Club event, and Lions Club and Chamber event. The band raised over $15,000 performing at these small events. Additionally, the members individually raised thousands of dollars when the community came together and hired them for small jobs like babysitting, painting, lawn care, and trash pick-up. Many band members sold enough pie and cupcakes to pay their way.

Also, the concert must be large enough to encourage the band members to change their rehearsal attitudes, show up to rehearsal, attend extra rehearsals, and sectionals, and practics their parts. The Carnegie Hall performance changed the Seguin High School band in many profound ways. The response used to be, “That’s impossible,” but now the response is “Okay, let’s figure it out.” The Carnegie performance has changed not only the band program, but the community.

Stan Mauldin has been teaching since 1979 and is in his first year at Seguin High School.

Practical Score Study for the Busy Band Director

Lawrence Stoffel

Friday, December 22, 12:00 p.m.

Mark your scores in color to find quickly the information you need and make the most of rehearsal productivity. There are different and useful color code systems, and each has its particular merits and purpose. This color code system highlights information printed in the score. By highlighting discrete information found in the score, the conductor’s eye is trained to target on a particular color to see dynamics, tempo, beat patterns, and other specific information. (You’ll want to use erasable color pencils.) Tempo markings are highlighted in green. Meter and beat patterns are marked in orange. Loud dynamics are highlighted in red and soft dynamics in blue. Any additional information found in the printed score can be highlighted in yellow.

Here’s a bonus to this score study clinic: Come to this session to learn what makes The Star Spangled Banner so difficult to sing. The answer is found in its form and function. (Hint: It really doesn’t have much to do with the range of the melody.)

Lawrence Stoffel, Professor of Music, is Director of Bands at California State University, Northridge (Los Angeles).

Teaching the Rhythm Section the Nuances of the Groove

Chuck Webb

Friday, December 22, 2:45 p.m.

It seems logical that when playing faster tempos we should concentrate harder, dig in, increase our rate of breathing, and grind it out. After all, if you are running a sprint you have to work harder that if you are taking a leisurely stroll, right? This makes perfect sense, but when trying to make music groove at fast tempos it is the exact opposite of what we should do.

To make fast tempos feel good we have to play a trick on ourselves and do the opposite of what seems natural. It is important to slow down our breathing, relax our muscles (our chops), and think in larger time groupings as opposed to being aware of small subdivisions. For bass players this may mean not digging in as hard and thinking of only the first beat of each measure in a fast walking line, even though you are playing four notes per measure. For drummers it may mean using more rebound so that one stroke generates two or more notes. For chordal instruments it may mean letting more space go by and playing more sparse comping figures. Playing fast tempos is challenging, but by practicing these tips you will soon learn to make the quick tunes sound comfortable and relaxed.

Chuck Webb is a first call electric and acoustic bassist who has toured the world many times, performing with such notable artists as Aretha Franklin, Ramsey Lewis, David Sanborn, Al DiMeola, Grover Washington Jr., and Freddie Hubbard.