Charles A. Maguire is the founding artistic director of The Desert Winds, a Las Vegas-area auditioned community wind ensemble that will perform at the Midwest Clinic this December. Says Maguire, “Today, the American community band is a movement that is growing. There are many well-established bands still in existence that have started to push the limits of what is possible with community musicians. The idea that community bands represent lower quality performances with less talented musicians has started to erode.” In addition to his artistic duties, Maguire is an educational consultant for band directors within the Clark County School District, which includes the cities of Las Vegas, Henderson, North Las Vegas, Boulder City, and Mesquite. He earned a Bachelor of Music Education from Troy University and a Master of Music degree in Wind Conducting from the University of Alabama, where he was the assistant conductor of the University Wind Ensemble. He is near completion of the Doctor of Musical Arts degree from UNLV, where he is a student of Thomas G. Leslie.

What initially prompted you to start conducting the church orchestra that eventually became The Desert Winds?

In 2009, I found myself drawn to staying in Las Vegas even though teaching opportunities were coming from many other parts of the country. I had completed my coursework for a D.M.A. at UNLV and wanted to continue conducting while maintaining my home here. My good friend Richard Brunson was leaving town to take a position in Wisconsin and told me he had recommended me for the conductorship of The Desert Spring Arts Orchestra, which was part of an outreach of the First United Methodist Church. I interviewed with the president of the organization and took on the position in August of 2009.

As you began conducting what we now know as The Desert Winds, was performing at Midwest part of the plan?

When the original ensemble evolved from a fledgling orchestra into a dectet of wind players, the initial focus was to save the organization from collapse. The recession of 2008 affected Las Vegas later than most of the country, and many musicians in town left for better opportunities. Luckily, the wind players in the group were mostly band directors who had secure jobs within our school district. As the ensemble grew into a community band and then an auditioned community wind ensemble, the plans have adapted to mirror the need for continued musical growth. The plan to audition for The Midwest Clinic was first discussed in the fall of 2014 and became a concrete goal during my attendance at the conference last year. There is an immediate feeling of inspiration when one attends The Midwest Clinic. Its historical significance to our profession coupled with The Desert Winds increasing quality made the decision clear.

How did you approach Julie Giroux to commission her for The Desert Winds’ Midwest Clinic performance?

When my father passed away, I witnessed love and sorrow simultaneously filling the chambers of my mother’s broken heart. It is something that you cannot fully explain or understand until you have come to this place in life. For my healing, I needed to have my father’s story written down but in a way that would be unique for me. Julie Giroux has long been a favorite composer of mine, and although I had never had a conversation with her, I became familiar with her through her poignant social media postings on healing, loss, and love. I realized that she might be the person to write my father’s story but it took some time for me to reach this conclusion.

As an undergraduate at Troy University in Alabama, I had an incredible experience learning from many fine composers. My first thought was to have Robert W. Smith or Ralph Ford compose the work for my father, but I didn’t want their experience with me as a student to influence a piece that was in remembrance. It is difficult to know if my being late for Ralph’s 8 a.m. theory class or missing one of Robert’s dress rehearsals would have influenced what they would have written. My personal growth as a musician and teacher were influenced heavily by them, and ultimately I felt that this piece needed someone from the outside to look in on my life to fully realize the artful healing that was needed.

I sent Julie a message at the beginning of April after The Desert Winds team had our initial Midwest Clinic plans established. At around midnight on April 27th, she asked if I was able to talk on the phone. We touched on many things during our discussion of the piece and I found myself feeling like she had been in my life for all of my years. I was able to talk to her openly about my father and the impact his passing had on my mother. Before a note was ever written, I knew that the piece would be a journey of healing for me, and that she would get something really special out of writing it. She captured my father’s story brilliantly. In many ways, this is the most difficult piece I have ever conducted because Julie has forced me to look in the mirror and face my heartbreak. She has masterfully created a path to understanding, reconciliation and love through the music of HearthStone. Performing this work with your musicians will guarantee deeper understanding and connection to the world around you.

Speaking to band directors who have low student enrollments, how would you suggest they create high expectations where previously there may have been none?

The first questions I would ask are “Why do you have low enrollments?” and “Are there ways in which you can improve your educational environment through consultation with administration, counselors, and other school stakeholders?” The first objective is to establish a consistency in enrollment. Quality is improved within clearly defined systems that have consistency as a foundation.

Once you have begun improving enrollment, then you have to establish clear objectives for your ensembles. Simple parameters will allow you to foster the quality that you desire. The most basic of these is to set students up for success, which starts by measuring where the students are. Inexperienced directors might feel compelled to play a certain piece because it is on a state list for their band, but students may not be at that level yet. It is better to pick something they can succeed at.

Many bands devote much less time to ear training then they should. Traditionally, choirs are able to hear things better than instrumentalists. To improve this skill set, we must have band students sing more. Getting characteristic sounds from the instrument and getting the correct pitch both relate back to singing and being able to hear pitch in the head.

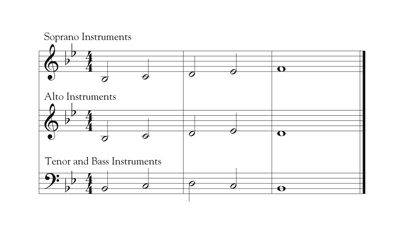

The first singing exercise that I teach band students uses the first five notes of the Bb scale. Everyone sings on la, because this syllable opens the throat, and I want students to get used to dropping the jaw and having the air be supported. I split the band into three parts: soprano instruments, alto instruments, and tenor and bass instruments. The exercise builds a triad.

Younger students do not begin band with an understanding of how harmony functions, but you can get them to hear these things without using advanced concepts and language. In other words, you can train the ears without overloading students with the technical terms.

Throughout the process of building a program, remember every part of your support system, considering how a good program looks to parents, administration, community, and students. Each of these stakeholders has a different idea of what a good program is, and until you can educate them on excellence through regional, state, and possibly national performances, the path to the program you wish to build is through the hearts and minds of those people. Programming is key. Do not be afraid to make decisions; you know your band and its support system better than anyone else.

When I was in my first year of teaching at the high school in Goshen, Alabama, my principal would come to the band room just to hear us play My Heart Will Go On from the movie Titanic. This request frustrated me because I had so many things that I needed to accomplish with my students and this tune was obviously not listed among the standards that I wanted to perform with my band. I remember wondering what education can possibly be found in a pop tune. It took me years to realize that music education reaches beyond your classroom and your students. My principal was dealing with some pretty harsh realities at home. At the end of the year, when she decided to go into retirement, she told me that those private concerts for her allowed her to experience joy during a dark time. The following year, I got the band schedule that she had fought many directors about in years past. In one year, enrollment went from 14 to 61. The answers are not always right in front of you, and solutions can often be found in the hearts and minds of those who appreciate what you do.

How would you encourage directors who inherit underperforming groups to invest in their students in meaningful ways?

In my years of teaching, there has been no bigger joy than accepting difficult teaching positions and fostering programs in ways that no one could imagine. The first step to investing in your students comes from checking your ego at the door. At the end of your life, do you want to leave a legacy where your students found their one sure shot at a meaningful life in the lessons that you provided?

We must recognize that success comes in many different shapes and sizes and has little to do with awards and accolades. One student finally learning a Bb concert scale after three years of trying may be no less successful than the student who wins an audition. As an educator, you must accept that if knowledge is imparted and absorbed, your role has been meaningful and successful. Directors are a boastful bunch and we are quick to puff our chest out and display like peacocks the many honors and awards that we have received. Within that sea of accolades and awards is that one student whose life was made meaningful because of the opportunity to be a part of something bigger than oneself.

One particular Las Vegas teacher comes to mind when I think about how success should be measured. Elizabeth Reineke teaches at Bailey Middle School in Las Vegas, and she has had to adapt to the many difficulties that her students bring to her door each day. When those students enter, they get an enthusiastic smile and a fist bump from her, and those things change the trajectory of children’s lives. They come to her from broken homes experiencing daily violence that even our news channels have grown tired of reporting, but for one hour a day, those students are encouraged through her thought-provoking engagement with them. Their music class serves as a refuge as they work to perfect their scales and music. She does not make excuses for these students but instead loves them through their experience. These students are successful if they have made it through one more day with one small moment of joy. Ms. Reineke provides their joy and in some cases a reason to live through their pain with the hope that tomorrow will be better. Adjudicators just cannot judge t hat kind of success.

How does The Desert Winds contribute to the music education in the Las Vegas metropolitan area?

Las Vegas differs from many other large cities in that the developed parts of the town are not that old. We do not have the legacy of band students found in other major metropolitan areas. Many of our music students do not come from homes that included music, so our place in this community is unique to others. We have spent time building relationships with our community and building programs that allow audience members to feel welcome and part of the performances that we put on. We had about 1,000 people come to our Veterans Day concert because we met with veterans groups to let them know we were doing this for the community. Historically, art music has been reserved for the elite in society, and concert bands have an excellent opportunity to end these reservations and perform music for all.

The Desert Winds plays its opening piece with no introduction, and after that, I ask everyone to take out their cell phones, which is the opposite of what is expected at a concert. Our concert halls usually ban cell phones, so we have to get permission from them to do this. I tell the audience members they can take pictures, check in on social media, and post that they’re here and enjoying it. I also say if there’s something they don’t like, we are asking for feedback because we want them to be a part of the process. Orchestras these days are working hard to keep and expand their audiences. Knowing that this is a concern, our approach is to eliminate the things that keep people from choosing to attend concerts.

.jpg)

What is your process when programming a concert?

There are many considerations that go into programming for The Desert Winds, but my first consideration is our audience. For programming, we find the visual ideas and graphics draw people in. The entire season’s concerts are related to each other through visual or more tangible concepts. I work with a talented graphic designer who puts my thoughts and feelings about a programming season into a visual presentation. When our community comes to our concerts, we want to make them feel as welcome as possible.

When people come to the concert, they already have a visual of what the concert is going to be about, so they feel like they’re more a part of the process. Two seasons ago, we performed a season of colors entitled Colorations. Each concert was built around a color. Once the colors were established, the literature choices came into play. I always have a running list of works that I would love to perform and if these works fit within the concepts presented, they will get programmed. I always consider current events to see if there is something that has impacted our community and ask if there is a way to reflect that musically. Our goal is to present music that is as relatable to our audience as possible without trying to be something that we are not. We must remain honest and we do that through consistently reflecting humanity whether through cheers or tears. We perform truth.

What role does the march play in the modern music education curriculum?

In a rich and diverse band curriculum, music history is as significant as the study of fundamental playing techniques. In band, we assume the role of band musicologist and present the historical position of the march to our students in ways that are indicative of its significance. If a director finds that marches are uninspiring to conduct or so repetitive that they deplete the time allotted to teaching kids about “real music,” I must suggest that we revisit the trove of musical teaching devices found within a march. We must rededicate ourselves to learning the intricacies of how a march should be played and how to impart this knowledge. Only in a march can you find so many different styles, moods, tempos and compositional techniques jammed into one tiny package.

The basic idea of a march is that it is the opening, middle section, and finale of a concert condensed down to three minutes. There is a huge amount of information that comes from a march. One of the most basic teaching devices in a march is articulation. Any band director who just plays the page and moves on hasn’t really dug in to it. Staccatos have to be defined; a British march will have a different type of staccato than a Sousa march. We have to be creative but clear in how we describe articulations because the staccato is not just a staccato. That is the base point, but the articulation’s meaning depends on the style and time period, and we have to be able to draw from that.

In addition, nowhere else in a program are the dynamics as important as in a march. There are melodies and countermelodies, and decisions have to be made on when to omit a part or what should be brought out and when. Using dynamics to execute the performance is the best way to get a band to understand how dynamics work in just one piece. These elements exist in other types of music, but articulations and dynamics are more important in a march than in anything else.

Marches teach students the importance of listening. There are more unison lines with people in a march, and these need to be balanced well. Students light up when they realize there is something that’s been going on for a month that is finally brought out. Things start clicking for them as far as listening and how to listen across the ensemble.

We have 48 high schools in the area, and last year at festival only three bands played a march. Only one of them did it well. I wonder if teachers are afraid of marches or perhaps just don’t like them, but marches are part of our heritage. If one really becomes intimate with the march, rehearsing any other form of music will become a breeze. If you truly believe that marches are predictable, you need to adjust your approach. There is joy in marches if you are willing to take the time to find it and use it.

What role do community bands play in the current evolution of the American wind ensemble?

You can’t discuss American music history and not touch on the significant role that community bands have played throughout American history. We have seen the community band rise up from military and ceremonial needs to becoming a major part of culture in small towns everywhere, but with the implementation of school band programs, for a while community bands dwindled in numbers. However, each year at the Midwest Clinic, you can see that community bands are programming and reaching for higher artistic integrity and more meaningful programming. We have not reached the full potential of what is possible and the journey is an exciting one.