I often hear directors plead with students to play more expressively in lyrical settings. Sometimes they tell an anecdote intended to inspire the players and help them connect with the music more. Frequently, I witness them instructing the students to execute a larger crescendo. Most of the time, they simply tell the students to “play more expressively,” as if that alone will produce the desired change. It is vital to develop a variety of pedagogical tools that can achieve that purpose.

Pablo Casals, the famous cellist and conductor, once said, “all music is a succession of rainbows.” He believed that music must have a natural ebb and flow like the changing tides or the seasons. Casals was highly celebrated for his moving interpretations of many pieces regardless of the genre. The essence of his philosophy can be distilled down to two simple devices: crescendo and decrescendo. Like the arc of a rainbow, every phrase must have a natural rise and fall. I often tell students that music must never be static. It is rarely appropriate to play a phrase with no dynamic change; there should always be a sense of growth or decay.

I use the analogy of the monitor in a hospital room: we know a person is alive because they have breath and pulse. Both of these vital signs are equally important in music-making and must be present at all times. I call this the to/from/at principle: All music is going to, coming from, or arriving at a given moment. The at moments are resting points, such as fermatas, and occur infrequently. The majority of music is going to somewhere. This is true not only for the melodic line but for the accompaniment parts as well.

The most practical way to determine when to do each is to follow the natural contour of the line. Performers should crescendo when the line ascends and decrescendo with the line descends. There are exceptions to this, of course, but performers should trust their intuition when making these decisions. By having students contribute their ideas, they will develop a sense of ownership, which ultimately creates more expressiveness in their playing. Identify the target note or the height of each phrase. After developing a collective interpretation, be sure all players are committed to the same phrasing so the expressiveness is obvious and intentional.

When executing crescendi on sustained notes or longer phrases, it is often effective to delay the growth of the crescendo, reserving more of the impact for the end. This type of crescendo is similar to the shape of a trumpet in that the tubing remains relatively narrow until it flares at the end of the bell. This shape is also appropriate for many percussion instruments to ensure that their sound does not mask the winds. Conversely, when playing a decrescendo, performers should stay louder longer so that their musical line maintains intensity and doesn’t disappear unintentionally. When writing in additional crescendi or decrescendi in the music, be sure to add dynamic levels to indicate how loud or soft the change should become.

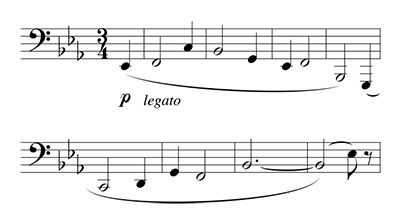

Note grouping is another critical device for creating effective phrases. Richard Floyd, retired professor from Texas University, uses the phrase, “Black notes lead to white notes.” That is to say that notes with shorter rhythmic values such as quarter and eighth notes move toward half notes and whole notes. This is akin to the well-known phrase, “Bring out the moving live.” In a clinic with my band, Floyd demonstrated this idea with the Chaconne melody of Holst’s First Suite in Eb:

Note grouping also requires an understanding of weak and strong beats to create metric accents. Depending upon the meter and style of the music, some beats are naturally stronger than others. The anacrusis, more commonly called a pick-up note, must create direction toward the downbeat. To help students understand how the two work together, I describe the contour of a phrase as being on a macro level and note grouping as being on a micro level. The two concepts must be used simultaneously to create expressive phrasing.

In the pursuit of excellence with performing ensembles, we sometimes engage in types of refinement that are counter-productive to expressivity. While establishing good blend in an ensemble, it is still vitally important to hear the individual tone colors that make every instrument unique. It is not advisable to blend tone colors to the point of being indistinct or unrecognizable. There should be an inherent vibrancy to every combination of instrumental tone colors.

Similarly, while it is important for the ensemble to move together, this should not be the result of playing with metronomic pulse at all times, especially in lyrical cantabile pieces. Just as the musical line must ebb and flow dynamically, so must the tempo in slower music. A good starting point is to move the tempo slightly forward during a crescendo and to pull it back during a decrescendo. If the composer marks a tempo change such as ritard or stringendo, make sure that the change is audibly obvious. Too often tempo changes sound too subtle in performance or are lost entirely.

It is particularly important to insert space after releases. I find myself using the word linger frequently when working on releases. Depending upon the musical moment, I may even add a full extra beat of time between phrases as needed to honor the music. Similarly, make sure the players have enough space to breathe adequately; nothing destroys a phrase faster than rushing a breath. Additionally, Harry Begian always recommended holding the final fermata at the end of the piece longer than you thought you should. When listening to the recording afterward, you will discover that the extra length makes the conclusion more satisfying.

There are many standard expressive devices that musicians use, what I think of as our collective music consciousness. Kenneth Laudermilch has identified many of these in his book An Understandable Approach to Musical Expression. The one that I use most frequently with students is having them play a tenuto on the first note of slur groupings. This can be accomplished by leaning into the note dynamically (stress accent), by elongating the note (agogic accent), or by doing both simultaneously.

Lastly, encourage your players to make musical decisions and take risks. Music is organic and expressivity must be similarly cultivated. Over time, students will learn to make expressive decisions jointly as an ensemble, rather than individually. Teaching students to be responsive to conducting gestures is also vital to developing expressivity. Stephen Williamson, Principal Clarinet with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, recently performed the Weber Concertino with a group I conduct. As he worked with the students, he instructed them to pay respondbe responsive to him because he never plays music the same way twice. I remember reading the same sentiment in a book by Maestro Leonard Slatkin, where he describes conducting the same piece on a concert series in different ways depending upon his disposition on any given night.

I used to think that there was a right way and a wrong way to make music. It took me many years to recognize that there are only musical and non-musical decisions. While performance practice certainly needs to be honored according to the genre and time period, there are many valid and effective ways to play the same piece of music. Genuine music-making is deeply rooted in our biological and emotional cycles as human beings. It must be fluid and in the moment to be authentic. This is at the core of expressive playing. In our efforts to unify our students in performance, let us always strive to keep the music alive and breathing.