One of the biggest hurdles for students learning to improvise is moving from playing what amounts to a series of scales and arpeggios to playing well-crafted lines with good voice leading. Even those students who have made great progress in understanding the theory behind jazz harmony, knowing their chord-scale relationships as well as their arpeggios, will still have something missing in their playing. The best tool for overcoming this hurdle is transcription; this – and implementation of musical language gained through transcription – is the x-factor that transforms correct improvisation into great improvisation.

Transcription is writing out and studying an improvised solo of a jazz master. It is the most effective way for a student to absorb the intangibles of jazz playing such as time-feel, phrasing, and expressive gestures. In addition, improvisors encounter many common chords and chord changes, and transcription is also is an excellent way for a student to glean language that can be used over these.

As they learn more and more jazz language, one of the best things young jazz players can do for themselves is begin an improvisation notebook filled with the bits of language they pick up organized by possible application. The four most common applications are material that works over a I chord, one-measure ii-Vs (usually two beats of ii7 followed by two beats of V7), two-measure ii-Vs (a measure of ii7 followed by a measure of V7), and a page of altered dominant lines, such as, flat 9 sharp 9, and flat 13. Collecting material for these four sections will provide more than enough for a high school student to build a firm foundation.

Getting Started

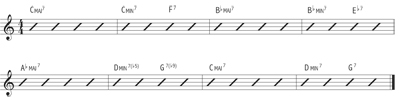

Shown below is a set of chord changes with numerous one-measure ii7-V7 progressions. Inexperienced students would likely approach this progression by practicing the appropriate scales and arpeggios and then using that material as a jumping-off point for their improvisation. However, by incorporating language from the jazz lexicon, meaning a passage from a transcribed solo, the student will not only have more success navigating the harmony, but also will sound much more authentic. The first step would be to direct the student to a solo with language that is appropriate for the harmony under study.

Find and transcribe language that fits the material under study. It is great to have contemporary favorites like Mark Turner or Chris Potter, but to really get serious about this music and studying it, go to the people your favorites studied – masters from 1955-1965 who forged this language. These dates aren’t absolutely hard and fast, but that is our common practice period, when the rules of bebop and straight-ahead jazz improvisation were codified and put into widespread use, beginning with Charlie Parker in the mid to late 1950s and continuing through John Coltrane and Sonny Rollins.

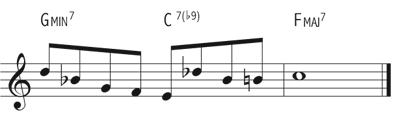

For the chord progression on the previous page, the following piece of language, transcribed from a Dexter Gordon solo on “Smile” from Dexter Calling, will provide plenty to work with.

The line has many song features, including good voice leading (note the 7-3 resolution between the Gmin7 and C7(b9)), as well as the use of an altered ninth on the dominant chord for more color and stronger voice leading to the Fmaj7. Plus, it sounds good.

Master the Language

Before using it in the chord progression under study, students must gain command of it. Although the only way to master a line is to play it by ear in every key, I usually only write each bit of language into my improvisation notebook in the key of C for ease of study. I never write the same line in all 12 keys.

Students can practice the line any way they can think of, including ascending chromatically, descending chromatically, and through the circle of fourths or fifths. While moving the line through the keys, different technical challenges will present themselves. Negotiation and mastery of these challenges will reap great rewards in the development of the student’s technique as well as the student’s ear.

Analysis and Application

Encourage the student to find all the places in the chord progression in which the language under study might fit. This will mean transposing the line into a number of keys. It is best to keep the notes in their original form as much as possible, but the language can also be tweaked to fit the harmony. A good rule is if the line has to be altered to make it function over the harmony, then it should be. If the line still functions over the harmony with color or altered tones, then these notes can be left as they are. In the case of the chord progression below, the line is altered in measure six to fit the Dmin7(b5) chord, because the regular fifth doesn’t fit the harmony. Meanwhile, the section of the lick that falls on the dominant chord has a flatted ninth, but this can be left alone because it not only works with the chord but also provides strong voicing leading and a rich color. In this case, a solution would look like the example below.

Practice versus Performance

This is not a solo to be used in performance, and I would caution against ever putting a solo together piecemeal based on various pieces of jazz language that have been transcribed. The above example is only for practice, and the goal is for students to be able to play that language in all the keys to which it can be transposed here without having to work at it; it should sound natural, not forced. While practicing this language, the student should be extremely deliberative and patient. There should be many repetitions of the progression in which the student plays only the line under study in the appropriate places.

Once the line feels natural I encourage students to add improvised material both before and after the line. The challenge then becomes moving from improvising material to logically setting up the piece of language and then moving back into improvisation. The idea is for students eventually to be able to pull out all or part of this line during an improvised solo; at this point that piece of language is so absorbed that elements of it come out in improvisation without having to be so specific about it. I liken it to having a conversation. We all have an 800- to 1,000-word lexicon that we use, but each of us sounds like an individual when we speak. In a conversation people both use the same lexicon, but we each have individual, original thoughts that make use of that material.

The improvisation notebook is an ideal place to collect the ideas students have researched and studied through transcription. As students develop and glean more and more language, they will find these books invaluable not only in preserving ideas but also in mastering them to the point that elements of them can be used spontaneously in improvisation. Rather than a rudimentary language based on scales and arpeggios, they will be developing an improvisation language based on the masters of jazz themselves.