Technical mastery is key to not just playing the bass well, but enjoying it more. Bassists sometimes struggle with aspects of arco, pizzicato, fingering, and shifting. Here are some tips on overcoming common errors and difficulties.

Bow Placement

Beginning bassists are generally taught to start down bows at the frog and up bows at the tip. For young players, it is necessary to develop the muscle tone to have an even bow and control at both the tip and frog. Getting control at the frog is fairly simple, but getting the bow to support what you want it to do when it is at the tip takes more practice. Starting up bows all the way at the tip builds that muscle tone so tip control is as developed as that of the frog.

For students learning bow control it is sometimes helpful to divide the bow in half so students get a sense of what portion of the arm drives the bow. From frog to midpoint, the bow should be driven from the shoulder and the back. From the midpoint to the tip, the bow should be driven from the elbow to the hand, so the elbow opens up for the upper half of the bow. Which part of the arm is the focus depends on whether you are playing in the lower half or upper half of the bow. My teacher, Frederick Zimmermann of the New York Philharmonic, would get a piece of chalk and make a mark at the center of the bow. Chalk is ideal because it can be brushed off the stick of the bow before a performance so it will not be a distraction.

Because of the way bowing has usually been taught, students assume an up bow is always at the tip and a down bow is always at the frog. However, the best choice might be a down bow starting near the tip rather than at the frog, and such choices are just as important as whether to use up or down bow. This is a nuance that raises good playing to artistic playing.

The correct way to choose bowings is to first find a musical arrival point, such as a phrase ending, cadential resolution, or climax note. A piece might begin with simple alternating down and up bows, but which to use in measure one may be determined by what happens in measure five. If there is an extremely clear arrival point, then it is usually ideal to play a down bow there and work backward.

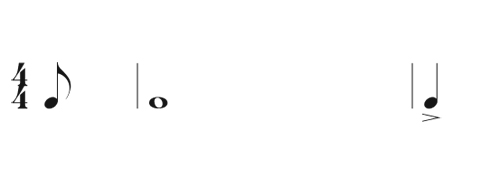

In the above example, the quarter note is a clear arrival point and should be a down bow. Because of this it would be ideal for the preceding whole note to be an up bow, and this makes the eighth-note pickup awkward. Continuing the pattern means the pick-up eighth note should be a down bow, which students may assume means starting it at the frog. However, having to traverse the entire length of the bow for that eighth note will make it unnaturally accented, too thick, and too long. The correct solution is to start the down bow in the upper third of the bow so there is just a small amount of bow available. I have met many bright young people who would be diligent about this if they knew it, but it had never been explained to them before. When I assign bowings and say something like “This is going to be a down bow placed at the tip,” I receive blank stares from students who have never heard of this idea.

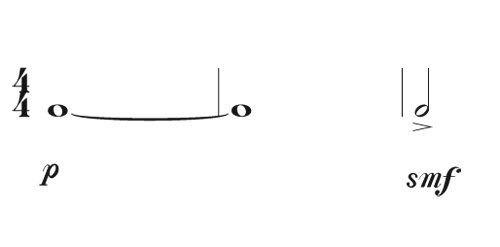

If a half note takes the place of the eighth note, as in this example, the down bow should start in the middle of the bow so there is a little more length available. If students start the half note too high on the bow, they run the risk of running out of bow, or they may have a thin sound as they move the bow slowly in an attempt not to run out.

Students do not always realize how close to the end of the bow they are. There doesn’t seem to be the muscle memory sense that I was taught to develop as a student. My teacher would hold a method book above my bow hand and tell me to stop the bow an inch beyond the chalk mark in the middle. I was supposed to know by muscle memory the position of the bow arm whether I was one inch or two beyond the middle. For tip control, he would have me practice stopping three inches from the tip while blocking my view with the method book. If it was only an inch before the tip, I would have to try it again. Such games and challenges were great way to develop a sense of where I was on the bow.

Bow Speed

Some bassists use the same bow speed regardless of what they are playing. This is like driving a car at the same speed, whether on the highway or in a residential area.

In the following example, the tied whole notes should be one long up bow.

The passage is not loud, so bassists can play two bars of up bow at a slow bow speed. At an average speed, however, they might run out of bow and have to switch directions, which destroys the intent of a long, unbroken note. For students unused to thinking about bow speed, this is difficult, and they often adjust the music to accommodate bow speed instead of the other way around. Planning bow speed is just as important as planning which part of the bow to start a bowing.

Pizzicato

The differences between the pizzicato in orchestral music and that used for jazz bass are striking and can color or shade a piece improperly if care is not taken to employ the correct style. The difference between classical and jazz pizzicato is comparable to the difference between a jazz vocalist and an opera singer. Each is wonderful, but the styles are extremely different and will sound strange in the wrong place. Imagine the beautiful pizzicato line in Bach’s Air on the G String played jazz style. It does not work.

Orchestral pizzicato on the bass is done the same way violinists, violists, and cellists play pizzicato. The thumb is gently supported on the edge of the fingerboard, and the bassist holds the bow with the third and fourth fingers. The motion is to pluck the string with the tip of either the first or second finger, or both together in a forte passage. Some players can alternate between the two fingers for fast passages. There is a circular motion that the hand adopts to get the note to ring. Most of the time, bassists are holding the bow while plucking because they will likely go back to arco soon. The German bow should hang down, while the French bow sticks up. Occasionally I see German bow players notice their French bow colleagues with the bows up, they then try to hold their German bows up as well. The German bow isn’t supposed to be held that way, and it is awkward and inefficient to move it into that position from the standard German grip. I also see French players point their bows down, and this is just as bad.

German Bow Pizzicato

The German Bow should hang down from the player’s third and fourth fingers during pizzicato.

The hand comes off the string after pizzicato in a smooth, continuous motion.

German Bow pizzicato bow hold, underside view.

French Bow Pizzicato

The French Bow must be held pointing upwards during pizzicato, as is a cello bow.

French Bow pizzicato bow hold, underside view.

The string is plucked during pizzicato.

The hand comes off the string after pizzicato in a smooth, continuous motion.

Jazz bassists usually do not hold the bow while playing pizzicato, and the hand position is entirely different. The thumb is downward and parallel to the fingerboard as well as against it. They use the entire first finger to pluck the string, and the string is played with a downward feeling so the string springs back up.

Bass players should be familiar with different styles to produce what the conductor and ensemble require. Occasionally in orchestras, the principal bassist may be called upon to play a jazz bass line. Nuance in pizzicato is extremely important; there are subtle differences between jazz, bluegrass, and folk bass pizzicato styles. Where I am, in New York, there are many opportunities for studio musicians, and if you are hired to play something that calls for a jazz feel but cannot produce it, you will not be hired again.

Fingering

The main fingering problem I see is preparing a note that follows an open string. As soon as a finger goes onto a new string, the bow wants to follow. Many young bass players have insufficient independence of the hands.

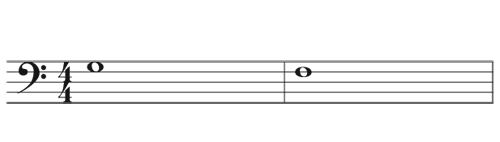

In this case, the G is open, and the F would be fingered with the second finger on the D string.

Students should already be fingering the F while playing the G. When the F is already fingered all that has to move is the bow. As long as the fingers are rounded, as they ought to be, pre-fingering will not cause any difficulties.

Waiting until the last possible second to finger the new pitch only makes things more difficult, because then in addition to a string change and a change of bow direction, a fingering change is now added. In legato passages, this can turn messy, so set fingers ahead whenever possible. Given the notes the bass strings are tuned to, and the most frequent keys used in elementary and middle school string music, this will happen often.

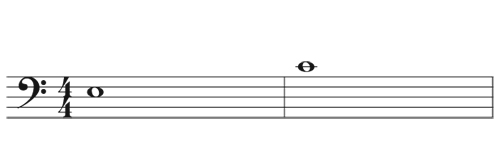

When shifting, a similar principle applies.

When bowing the E, which is fingered with the first finger, set the second finger on the G string (as shown below) in preparation for shifting up to the new pitch. In my day this skill was heavily emphasized, and students did not move beyond it until they could make a proper shift or a proper string crossing. If I spent two hours on two measures of a piece of music, that was time well spent, in my teacher’s opinion. My teacher used to say that when playing music with string crossings or shifts, it should be impossible to tell when they occur. The bass should sound like it has one string in legato playing. It is not always possible to place fingers ahead of time, but when it is, bassists should do so.

When preparing to shift to a second-finger C on the G string after playing a first-finger E on the D string, set and press the second finger on a Bb on the G string ahead while the bow is still resonating the first-finger E on the D string. Then, smoothly shift up to the C with the second finger while simultaneously moving the first finger onto the G string as well.