A classic article from October 1988

My first encounter with Joseph Mariano was at my entrance audition at the Eastman School of Music, for which I had prepared Poem by Charles Griffes and Syrinx by Debussy, the work I naively considered the easiest. I was anxious to play Poem because I had heard Mariano’s stunning recording of it, and I was determined to do my best after his inspiring rendition. During the hour before my audition I quickly reviewed the fast passages of the piece, but at the audition Mariano asked me to play only Syrinx. He politely thanked me and indicated the audition was over. Astonished, I asked if he wanted to hear Poem; he said no, but he would hear a G major scale, played slowly and slurred. The entire audition lasted five minutes.

Dismayed, I resolved not to attend Eastman. I was too inexperienced to understand that Mariano listened for line, phrasing, and color in every note. I recovered from the disappointing audition and attended Eastman, studying with Mariano during his last three years of teaching before he moved to Cape Cod. Throughout my studies with him, he exhorted me to remember the fundamentals. One of his favorite expressions was "back to basics," which he used to describe his method of creating and maintaining a strong foundation with the building blocks of long tones, intervals, scales, and arpeggios. Many students do not understand that pieces would be easier both to learn and refine once the basics are emphasized. Furthermore, Mariano stressed not only the notes of the technical material need to be reviewed, but also the musical concepts between the notes should be practiced diligently.

For Mariano, scale practice incorporated three important musical concepts, and I emphasize this same legato practice with my students. First, the scale involves horizontal playing: the tone quality, intonation, and direction of each note of the scale should be secure and clear. The inhalation should be quiet, the air flow smooth, and the fingering accurate yet unobtrusive. The student should fill the spaces or gaps between the notes, blowing through the notes. In other words, the sound needs to travel from the beginning of the first note to the end of the second, and so on throughout the scale. By applying this principle, the student concentrates on making clean attacks, controlled releases, and a legato singing tone.

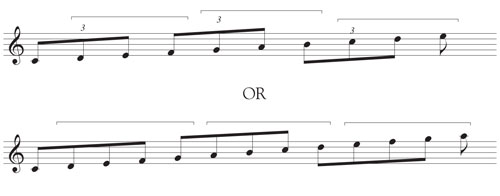

Second, scale notes should be grouped so that accents do not occur on the beat. Influenced by his teachers at Curtis, flutist William Kincaid and oboist Marcel Tabuteau, Mariano taught this concept of grouping notes in scale practice. The student brackets the notes as follows:

The first note of each beat becomes a resting point, without accent, and the second note continues the motion of the musical line. Valuable for performing with greater sensitivity and direction, this concept should be thoroughly ingrained in scale practice. John Krell also includes a chapter dealing with this concept of grouping in his book Kincaidiana, now published by the National Flute Association. (nfaonline.org).

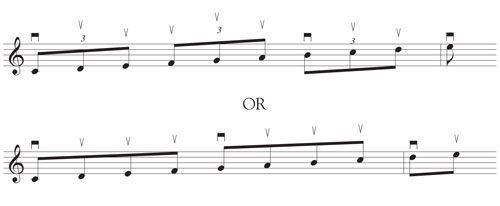

Third, the scale should have inflections of upbow and down-bow, a concept Marcel Tabuteau describes in the recording Art of the Oboe (Stereo #1717, Coronet Recording Company) as that which gives breath or life to the notes. This intrinsically relates to groupings where the inner notes have an up-bow inflection and move forward; the down beat of each group serves as a finishing or resting point, and thus has a down-bow impulse.

The up-bow feeling is similar to an inhalation, or question. The down-bow stress is similar to an exhalation, or resolution. In Kincaidiana, Krell describes this concept in terms of bowing, stating "the up inflection is identical with the up-bow feeling of a stringed instrument: the lifted part of the grouping is resolved on a down-bow impulse." Both concepts of grouping and inflection serve to propel the musical line forward with greater rhythmic vitality.

In practicing a scale, keep in mind the musical concepts of a singing legato tone, phrase groupings, and up and down impulses beyond scales into repertoire for natural phrasing, flowing line, and color in every note.