Teachers often tell students not to start the vibrato after the beginning of the note. If this has become a frequent comment at lessons, stop and give some serious thought to the problem. Beginning notes without vibrato is a common bad habit for instrumentalists and vocalists alike. Usually flutists either consciously use vibrato as a natural form of energy in the tone when it is produced unless they decide otherwise, or they mindlessly add the vibrato to the tone after starting the note, like spreading gray icing on cake, perhaps while trying to decide which shoes to wear in the recital. To really find out which kind of flutist you are, may require the help of a recorder. The truth may not be pretty.

If you are in the former camp, read no further, you already know where this road leads. If you find yourself in the latter, take heed. Starting the tone without vibrato is an annoying affectation and a cheap trick when used irresponsibly. It can also be an effective tool in capable hands, but ask any magician: using any trick too often is not only boring, it is bad for business. When people begin to find out how you really create the magic, then it is no longer magic.

Beyond this, there are more serious implications. Constantly starting a phrase without vibrato implies a lack of awareness. The fundamental purpose of a musician is to communicate; be aware of what you are saying when you play. In speech, if a person repeats the same thing over and over, he is not only at risk of admission to the psychiatric ward, he is a poor communicator. You do not always have to say something original, but to be effective you must be aware of how you say things. Learn how to say the same thing in different ways. To be blunt, if you are a habitual delayed-vibrato-starter, you are not only a seriously flawed instrumentalist; your artistic integrity may be at risk.

A Common Problem

There is hope, however. With awareness, this tendency is not hard to erase. There are many reasons why this ubiquitous habit of starting the note without vibrato is so prevalent, and indeed, tempting. Perhaps the tendency can be traced all the way back to the Baroque messa di voce, in which a singer would start a note softly, add a crescendo, and then end softly. Why not add some vibrato to that crescendo? Tempting indeed. As with vibrato use itself, the technique was part of the musical evolutionary process away from liturgical accompaniment into more personal and secular idioms. It was a popular device among the Italian castrati, and has remained firmly established in vocal tradition. Pop and jazz singers rely on the vibrato-less attack, partially because of their subject matter. Delaying the release of vibrato in the tone pulls at the heartstrings and heightens that sense of romantic yearning which is the lifeblood of popular music.

Flutists also take cues from our string brethren, where traditions become firmly established and take on the aura of religion. Listen to any of the great cellists or violinists of the past or present and there are many departures sans vibrato. Realize that those players are great, however, because they are in control of the notes. String students as well as wind students struggle with this problem. In string pedagogy, there is the urge to establish the intonation of the note before vibrating it. Vocalists want to get the vocal chords in vibration and find their note before adding vibrato, just as flutists want to establish tonal focus first. For all musicians it is the same. It is just easier to start without vibrato.

Develop the Habit

It takes energy and control to pulse the air column directly. There is a risk that the tone may not emerge as planned with the air column activated in such manner. The embouchure also should be ready to accommodate the pulsing air. It takes forethought and proper positioning habits to establish the embouchure comfortably before beginning the note instead of settling in after things get going. Ironically this trait can stem from the admirable practice of long tones. Flutists learn to begin the notes carefully and study the sound. Since it is easier to start notes without vibrato, it becomes a habit. In this case the vibrato sense is asleep but perhaps the imagination is as well. Try to consciously develop the habit of hearing the note before playing it instead of after. Articulation can also be a factor, as tongue use, embouchure placement, and starting the notes can be dependent in odd ways. With some types of attack it is possible to begin with vibrato, but not with others. Tension is a negative influence. The throat should be open and relaxed from the start of the note, just as a string player should relax the hand.

In appropriate cases, starting the phrase without vibrato implies that there is harmonic or other action which is to come which will inspire the release of vibrato into the tone. Indeed many phrases begin this way, but many do not. Differentiate between those phrases that warrant a clear release of energy at some point during the first note, and those that deserve immediate inflection with vibrato or more sober treatment.

Panting Exercise

Starting notes with vibrato is a skill, like standing on one leg or riding a bike. The air should pulse immediately when a flutist starts to blow. A great way to learn this skill is to study a puppy. They pant often and evenly to cool their bodies. Skilled vocalists tend to be skilled at a panting exercise that is common in vocal pedagogy as it strengthens the diaphragm muscle. This can work for flutists as well, as it helps with rapidly pulsing the air, a skill needed for the production of vibrato.

Without the flute, stand or sit comfortably. Pant with the mouth open or closed, although it is easier with heavy panting to keep the mouth open. It may be best to do this when alone as it can inspire unsavory comments from others. Make firm little puffs of air as if saying a silent ha, with no articulated throat sound at the beginning. Start slowly at first with each puff equal to an eighth note at q = 40. Make the puffs identical and rhythmically even. Then speed them up. Do not close your throat or grunt. Once this is comfortable, add the flute. The goal is to pulse the tone simultaneously with the attack of the air column, so remove the tongue from the equation at first. As with the panting, allow the air to generate from a puff, as if saying ha. Tonal focus is important, so the sound responds immediately. These tongueless attacks are great for activating the air column in general, and can improve playing in many ways.

I like to use the first part of Andersen, Op. 33, No. 2 in A minor, playing at a slow tempo, mf, about q = 60. Each note should get a sudden little staccato tongueless attack. This will work with any passage, but I do not recommend practicing this in the lowest notes because of tone production challenges. Increase the tempo gradually to around q =120. Then practice the same drill on a single note above the staff. When you reach the faster tempos with the separated notes, string the puffs together on the same note, to create sustained tones of short duration, maybe 4-6 pulses long. Later add longer notes with crescendos and diminuendos, and different attacks. It is especially useful to develop a dolce, gentle attack with simultaneous vibrato. Incorporate this into daily long tone practice and warm-up.

Once this habit of starting notes with vibrato is well established, explore the topic in the repertoire. There are many different contexts in which this practice has direct importance.

A Few Examples

Rossini, William Tell Overture

Because the harmony is static during the first two measures of the tune, there is no reason to delay the vibrato. Doing so sounds not only self-indulgent; it adds a layer of emotional intensity to an apparently simple pastoral melody. Immediate vibrato also puts the inflection of the phrase on the first note of the measure. This is the best choice in this case, but take care not make an accent. The triplets on beats 2 and 3 naturally send the inflection back onto the first beat of the next bar, so one must reduce dynamic a bit before playing them. This occurs easily with the inflection on beat 1.

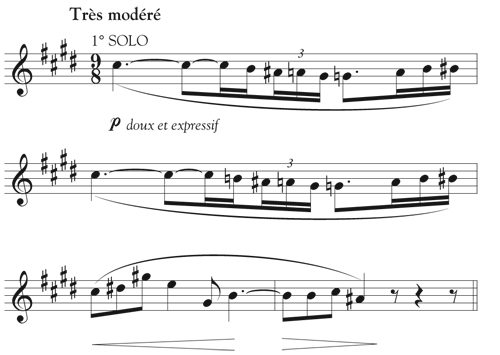

Debussy, Afternoon of a Faun

In the celebrated opening solo of Debussy’s Afternoon of a Faun the natural choice is to make the first note emerge discreetly with the vibrato already active. Note that there is no harmonic change during the duration of the first note. In fact, any harmony during the entire first phrase happens purely in the mind of the listener, since it is unaccompanied. (Debussy harmonizes it differently in each statement following the opening.) Because there is not a compelling musical reason to begin the C# without the vibrato, the most likely explanation for the occurrence would be convenience for the player, which is not a viable musical justification. It is really hard to start the note with vibrato and an inaudible attack. I do think the long note should have some action. Slightly increase the dynamic during the note so it has some motion in space as it approaches the moving notes. As in the Rossini example, the pure simplicity of the statement, without any drama, should rule the day. The fun is just beginning, and there is ample opportunity to dramatize later in the piece.

Poulenc Sonata, 2nd Movement

.jpg)

Context plays an interesting role when deciding how to start the second movement of the Poulenc Sonata. The famous opening features a short, ghostly, pale phrase, followed by a melody of the most exquisite beauty and sensitivity. These brief, rather directionless-sounding opening bars, played in canon with the piano, do not have passionate content, and are inconclusive as a musical unit. It is best to limit vibrato use here, maybe just enough to color the peak of the line. The phrase has no distinct arrival point. It is only understood after it is heard by the listener, with the beginning of the next phrase. Vibrato can begin directly on the F natural of measure 3. Play it without accent and gently articulated to signal the start of the melody proper. Reserved, balanced, and rather continuous use of the vibrato suits the initial bars of this melody best because of its harmonically restrained nature.

Flutists should also learn to start internal notes in a phrase discreetly but directly with vibrato. This is not a punch with the air column as in creating a vibrato accent (that was used that as an exaggeration technique in the exercises), but a gentle and immediate start of the vibrato.

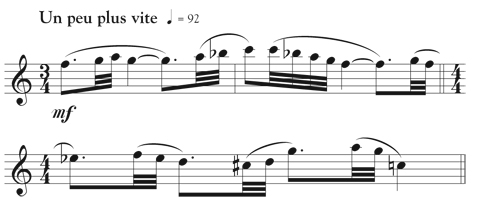

Poulenc, Sonata Movement 1

.jpg)

When beginning the Poulenc Sonata, it is natural to arrive on the E natural with vibrato but without accent. Since the famous 32nd notes function as an anacrusis, or pickup, they need not be emphasized with vibrato or harsh dynamic. Indeed the tone production of the first note in the p dynamic is the goal of all flutists’ practice. The downbeat E natural can receive the vibrato right away because of its natural primary inflection in the structure of the melody. The following structural D# and Dn can diminuendo slightly from the E, with the eighth-note Bn at the end of the bar fitting into the picture with plenty of legato, air speed and no accent.

Bach Suite No. 2, Overture

Similarly, when incorporating non-vibrato rapid notes into the melodic line, as in the Overture of J.S. Bach’s Suite in B minor, the longer dotted notes must have the vibrato (if one in fact decides to play the piece with vibrato at all) naturally and immediately without accent after each pair of French Overture-style 32nds. The second theme in the first movement of Poulenc’s Sonata is another case in point.

Poulenc Sonata, 1st movement, 2nd theme

In both examples the vibrato begins without the thrust of air from the diaphragm, creating the illusion of discreetly continuing the vibrato through the phrase. (Actually sustaining vibrato through the 32nds is perhaps not the best choice due to the heaviness of such use.)

The opposite is the case in the following examples. With the opening of Carl Nielsen’s Concerto, the agitated mood dictates that the opening announcement of the D natural begins with a strong attack, both with the tongue, and with the vibrato.

Nielsen, Concerto, Movement 1

This underscores the excitement of the moment. Easing into the Dn, which is sometimes done out of habit, seems contrary to the placement of the D natural at the top of the phrase, with the jagged 16th A natural pickup preceding, giving the phrase a softer, more tender, pleading quality in direct contrast to the stormy announcement of the opening.

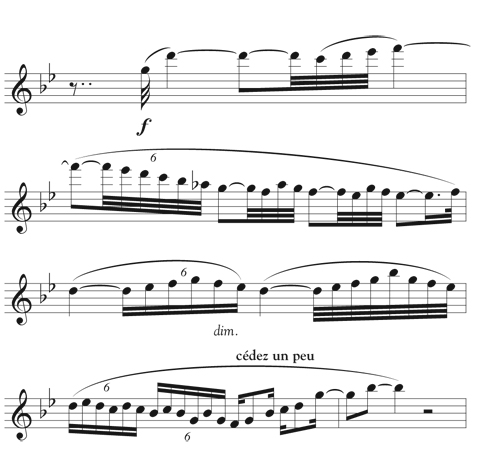

Hue, Fantasie

In the initial passage of the Hue Fantasie, it is important to begin the vibrato directly and assertively on the D natural following the G natural pickup. Again, using the direct approach with the vibrato enhances the direct and emphatic quality of the phrase. Later in measure 11 the same motif is repeated in a piano dynamic. Technically, the character of the motif should not change simply because of the softer level. Begin the vibrato directly on the A natural without accent, unless you decide to make the softer dynamic the dominant character. Then perhaps delaying the vibrato would enhance that notion.

Frequently initiating notes without vibrato, especially in older music, places the performer between the composer and the listener. Phrases become personalized. The player sounds like they are exaggerating their emotions, as if squeezing water from a sponge, superimposing them on the music. Romantic and Contemporary styles seem to tolerate this rhetoric, while the music of Bach and Mozart suffers from it.

Bach, Sonata in E Minor, BWV, 3rd Movement

In Bach’s Sonata in E minor, third movement, do not squeeze the vibrato into the sound when starting. It sounds too emotionally hyped. Also, the tempo should not be so slow as to draw attention to itself (perhaps q = 60), so that the long notes are of reasonable duration and the 16th-note passages can have linear shape without getting bogged down. The same applies to the opening of Bach’s exquisite aria “Aus Liebe will mein Heiland sterben” from the St. Matthew Passion.

Bach, St. Matthew Passion “Aus Lieve wil mein Heiland sterben”

Note that both examples have a very simple accompaniment figure. Vibrate the downbeat En tastefully right from the start of the note. Again, this makes musical sense, as the moving notes which follow lead us naturally to inflect the next downbeat. In both pieces, choose a speed and width of vibrato that do not attract too much attention. With exception of some notable composers such as CPE Bach, try to stay out of the way and resist swooning, it spoils the natural universal beauty of the music.

While the great works are inspiring, it is most efficient to practice beginning different kinds of notes with the vibrato using simple patterns of your own making. There is more clarity this way, and since you are generating the idea, there is less chance of becoming weary of the classics or formulaic in your approach to them.

No matter how accomplished flutists are, listening is a primary skill and source of inspiration. Listen before practicing instead of afterwards. Sometimes just sitting down with a recording of a great flutist playing one phrase and trying to imitate it is the best way to learn.

For examples I take my cue from the vocalists. Some of the operatic tenors are particularly good to listen to for starting their notes with vibrato. Also, the greats can really meld the vibrato to the tone and continue the vibrato through the phrase. I listen to Domingo, Pavarotti, and the popular Maltese tenor Joseph Calleja. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau is a model for tastefulness. Some of the operatic singers, particularly sopranos, have a very strong habit of sliding into the vibrato, so I listen to them with an awareness of the trait. I admire the stunning beauty of Kathleen Battle’s tasty and continuous shimmering vibrato, especially in Mozart. Renee Fleming is great to listen to for all aspects. The recordings of Nat King Cole are a joy to study for natural vibrato. On the jazz side, Stefan Grappelli is a master of vibrato use, as is the great rock guitarist Jimi Hendrix.

For model flute playing I find Jeanne Baxtresser’s recording of the Geiseking Sonatine and the Taktakishvili Sonata (New York Legends Series, Cala Records) positively infectious in terms of the lyrical vibrato use in the phrases. Notes begin with vibrato, particularly internal ones, far more often than not. For consistently energetic vibrato from the start of the notes plus enormous internal energy in the tone, nobody quite matches Moyse. Try to imitate a few phrases, and the hours melt away. Julius Baker was obsessed with the idea of starting notes with the vibrato, and his recordings are a testament to that.

Give these methods and examples a try and you will be surprised how quickly and easily you can overcome this dreadful habit. Make a short term focused project out of it, or just whittle away at it gradually every day. Mindfulness and awareness going forward are also important for the highly skilled professional, as bad habits have a way of slowly sneaking up. Recording practice is really helpful and efficient. Getting control over your tone in all respects can be very rewarding, and I can promise that your listeners will be glad you did.